Introduction

Data as of 18.01.2024

At the end of 2021, OVD-Info issued the first report on legislation against so-called ‘foreign agents’. Since then, there have been many changes to the laws and in the practice of their application. Including the fact that many laws have been combined — we are now talking about one main law that came into effect on December 1, 2022. It combined all the previous discriminatory practices contained in different laws on ‘foreign agents’ and added new restrictions and prohibitions to them. It also increased the criminal and administrative liability for ‘foreign agents’ and obliged them to submit new, more extensive reports to the Ministry of Justice.

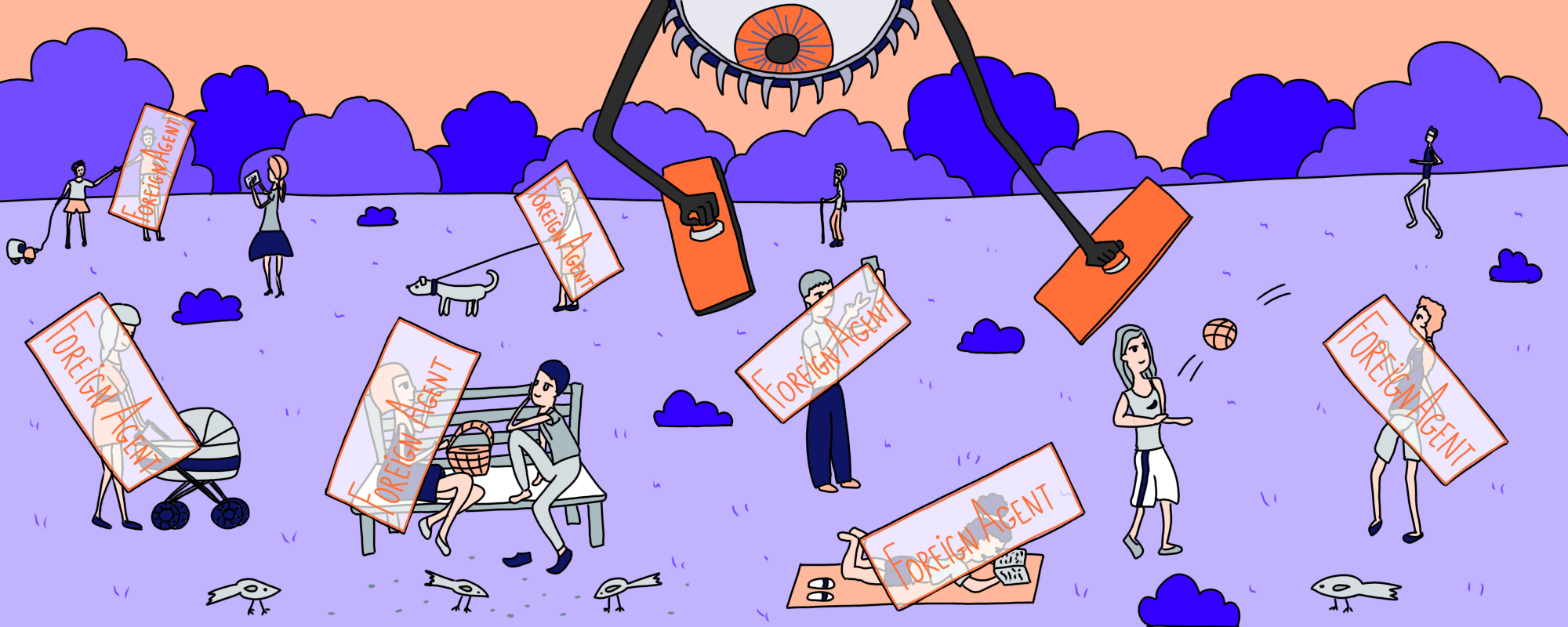

The practice of applying the law has also changed. Whereas previously the instrument of recognition as a «foreign agent» was primarily aimed at journalists, mass media and human rights activists, now this status has been extended to other parts of society. Standup comedians, musicians, writers, filmmakers and entrepreneurs have been recognized as ‘foreign agents’ over the past two years. The grounds for inclusion in the register have expanded: now, in addition to foreign funding, there are «speeches against the special military operation (SMO) and in defence of the regime in Ukraine, ” „discrediting the activities of the public authorities in the field of ecology, ” and „negative criticism of representatives of authorities at various levels.“ Thus, the Ministry of Justice officially recognizes that it is using this discriminatory law to persecute people who speak out against the war.

Thus, as of January 18, 2024, there are 855 «foreign agents» in the register, including individuals and organizations. Starting from 2022, the list has been expanded more actively and frequently: in 2021, 128 individuals and projects became «foreign agents», in 2022 — 211, and in 2023 — 283 — 2.2 times more than two years ago. This is how the «foreign agent» register looks right now:

The register of ‘foreign agents’ has long included organisations and people from a very wide range of activities, ranging from environmentalists to activists helping HIV-positive people. After the beginning of the war, the legislation on ‘foreign agents’ was used more frequently to persecute LGBTQ movements. During 2022 — 2023, for example, 20 organisations and individuals involved in supporting LGBTQ people were included in the registries. This is nearly twice as many as in all the previous years of the law.

In general, the distribution by areas of activity of ‘foreign agents’, as well as by gender, now is as follows:

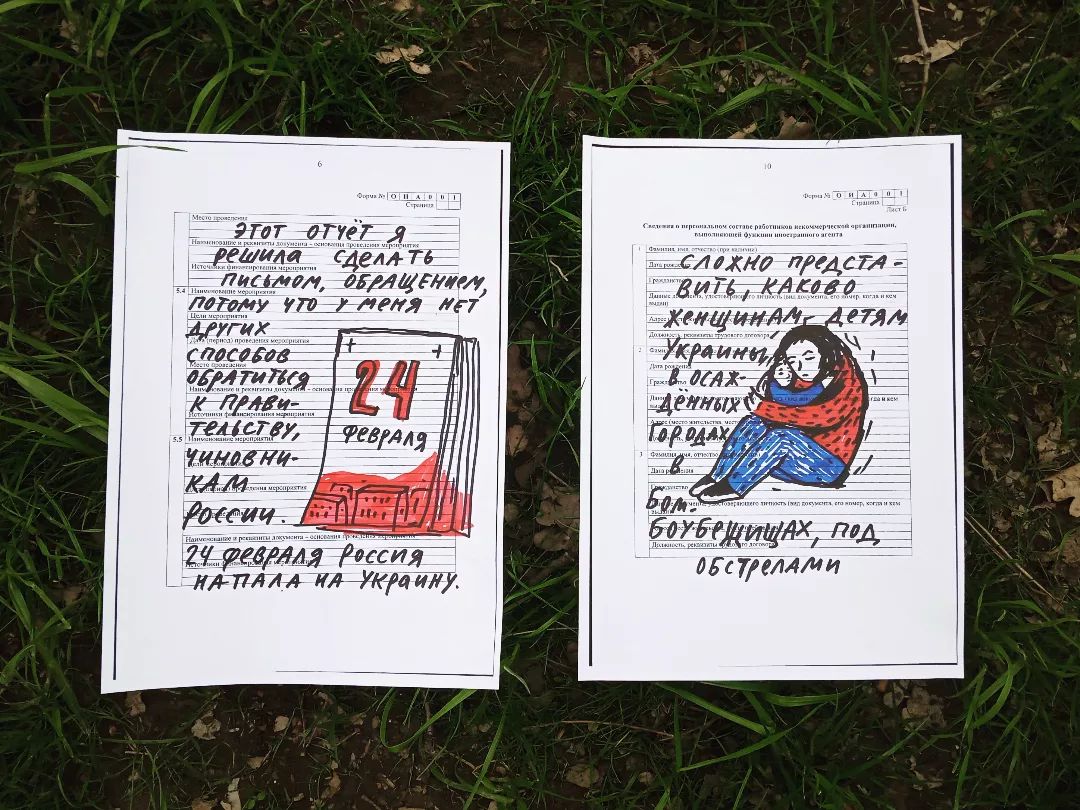

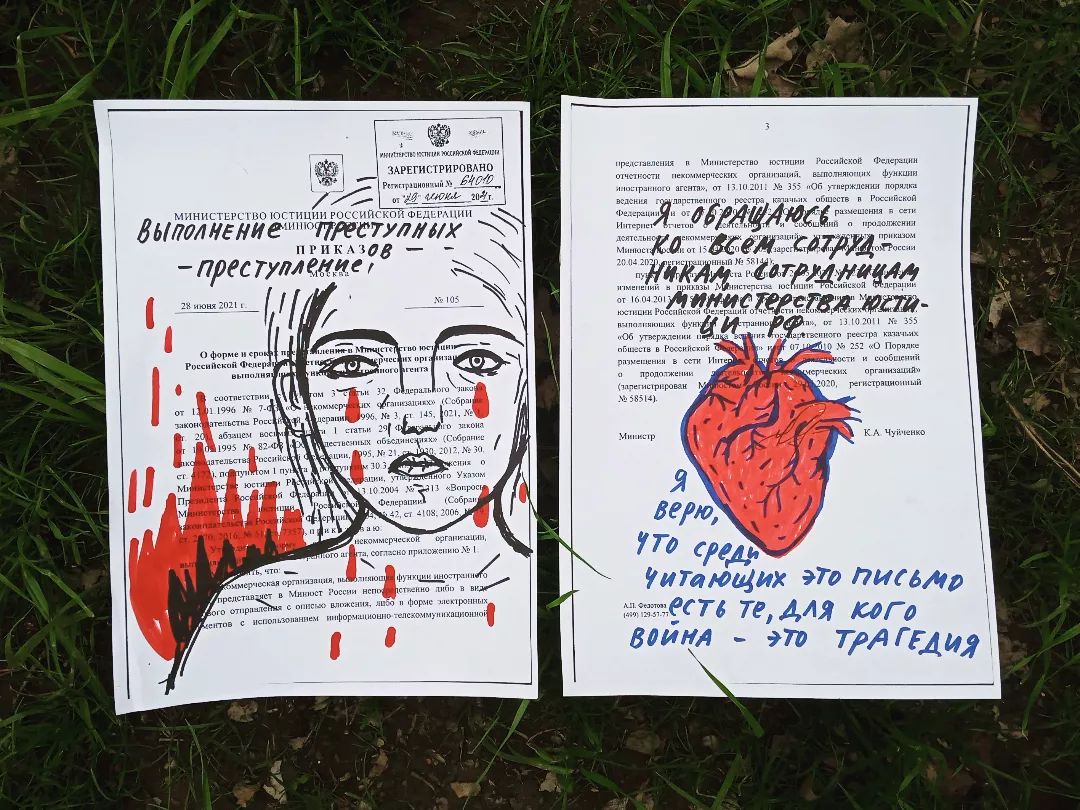

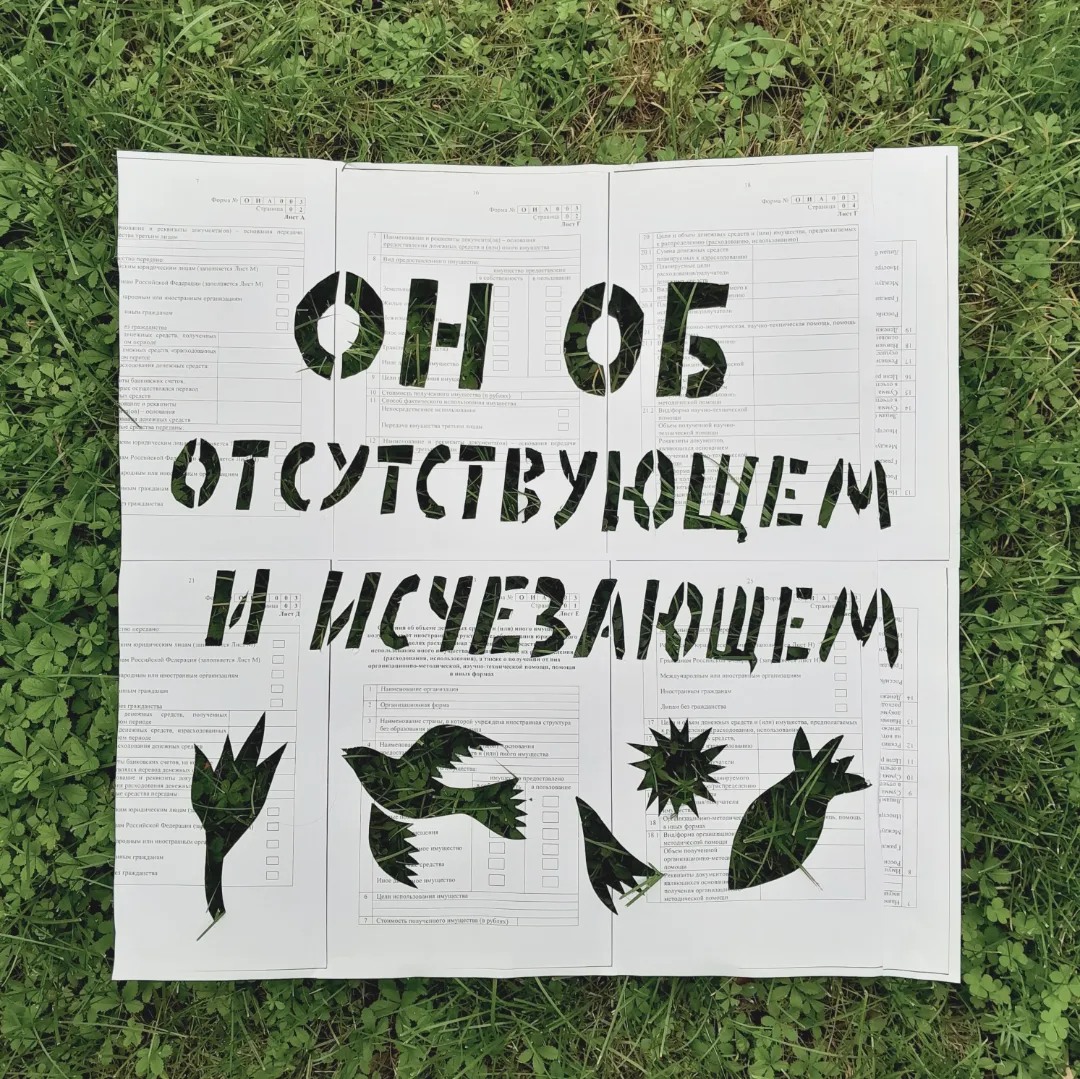

«I chose an artistic form of the reports because it makes more sense to me. I believe that the language of art is more precise and offers greater scope for expressing oneself. I could have written a post or made a video about my attitude to the Ministry of Justice, but an artistic expression offers a broader range of interpretations and a more direct connection with the audience. An artistic form for my reports to the Ministry of Justice is good because it is an exact opposite to the formal language, to the language of state violence.

I started creating these reports after the beginning of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As the war started, I understood that this was the way I wanted to express myself. This is my only channel of direct communication with the state machinery, with the body that has seized power in Russia

I am preparing my upcoming report I need to send by 15th October [2023] together with my followers from Instagram. I asked them to send me a single word for the Ministry of Justice, and I will then compose a text from these words and possibly add some pictures. I will send as many reports as needed. At least, I find joy in creating artistic statements, as I see it as an instrument to express my thoughts. This is important to me,» Apakhonchich explained.

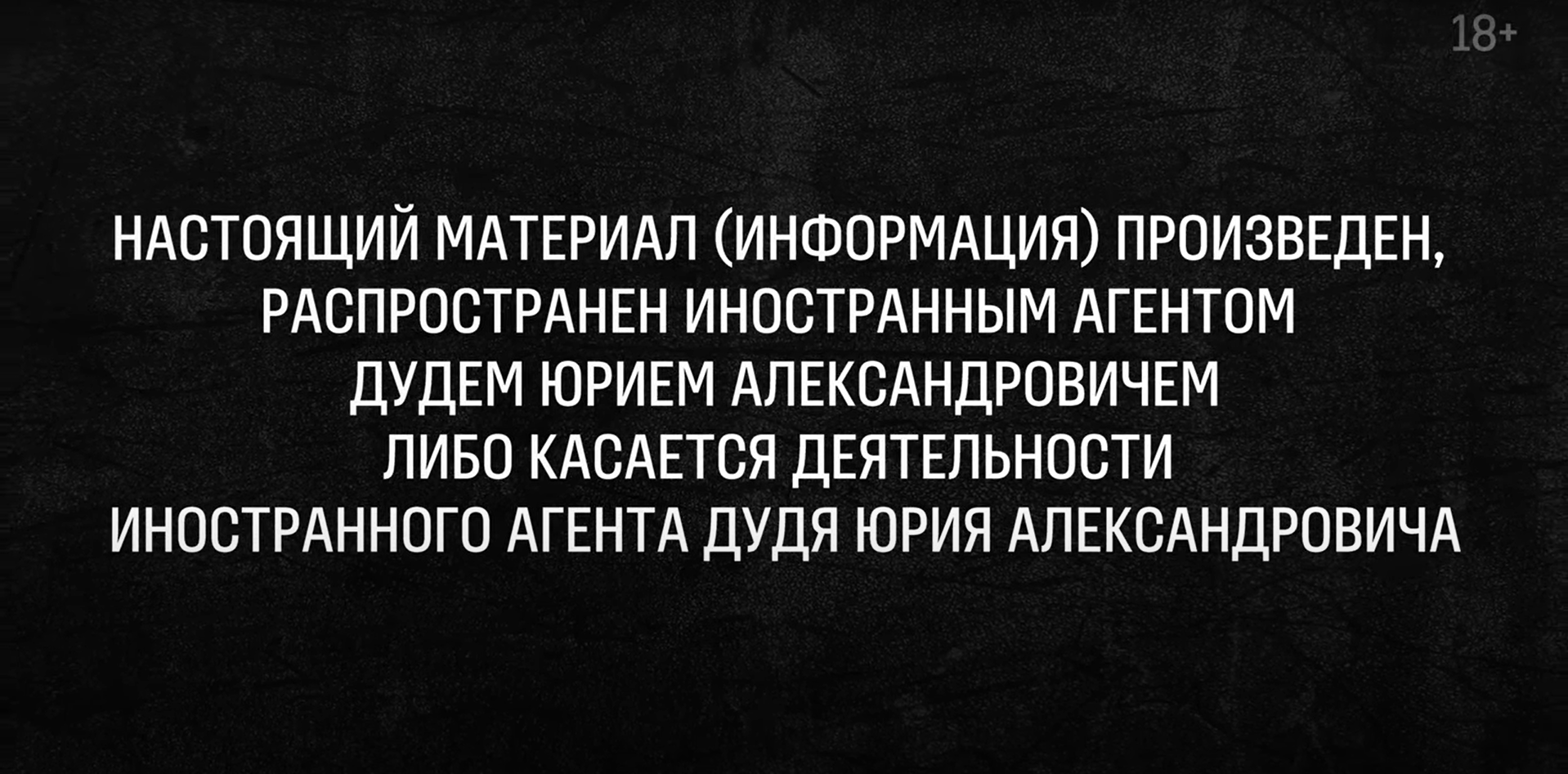

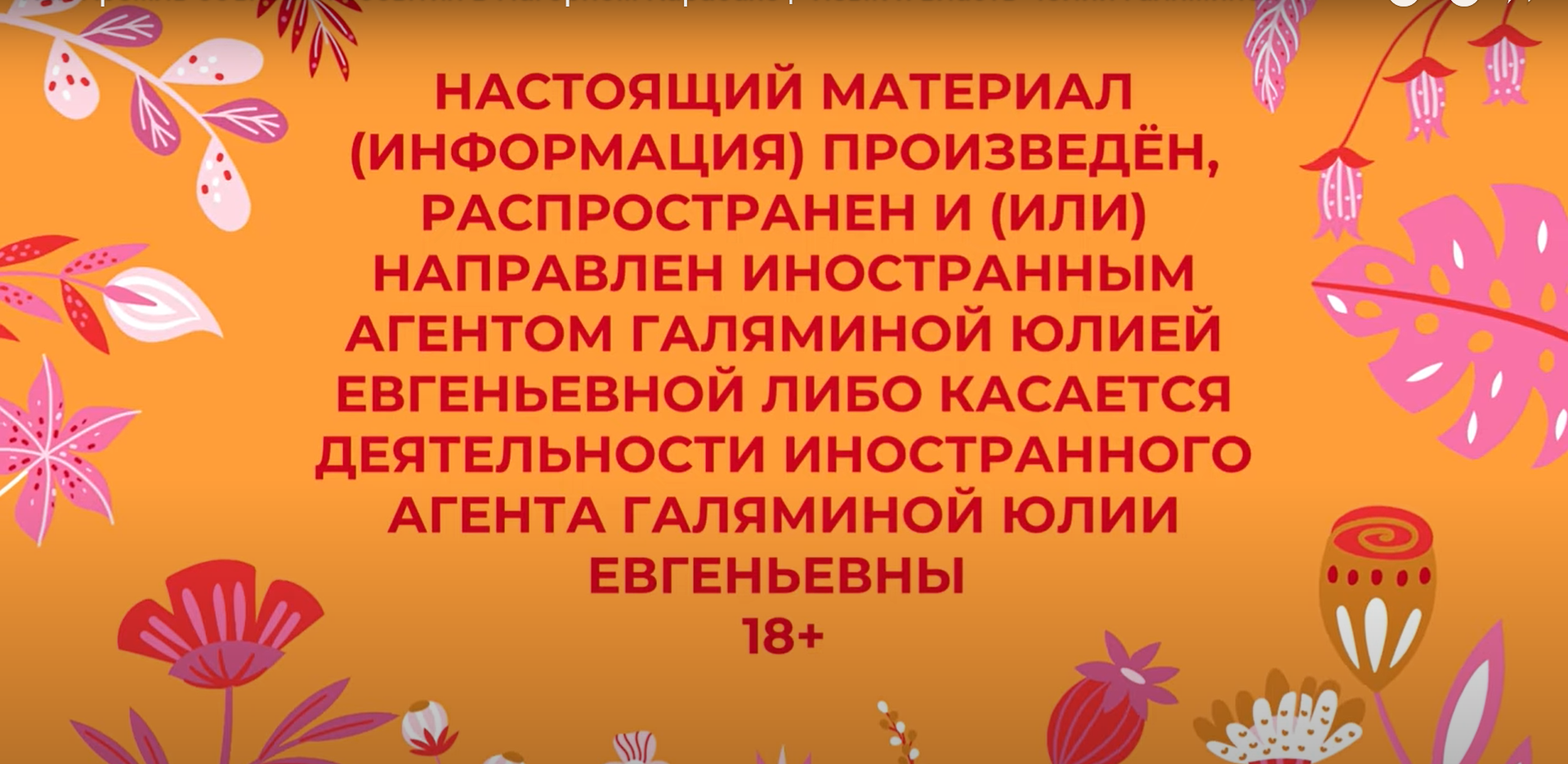

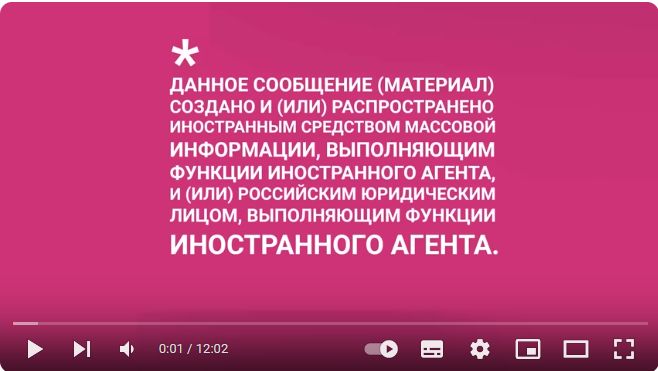

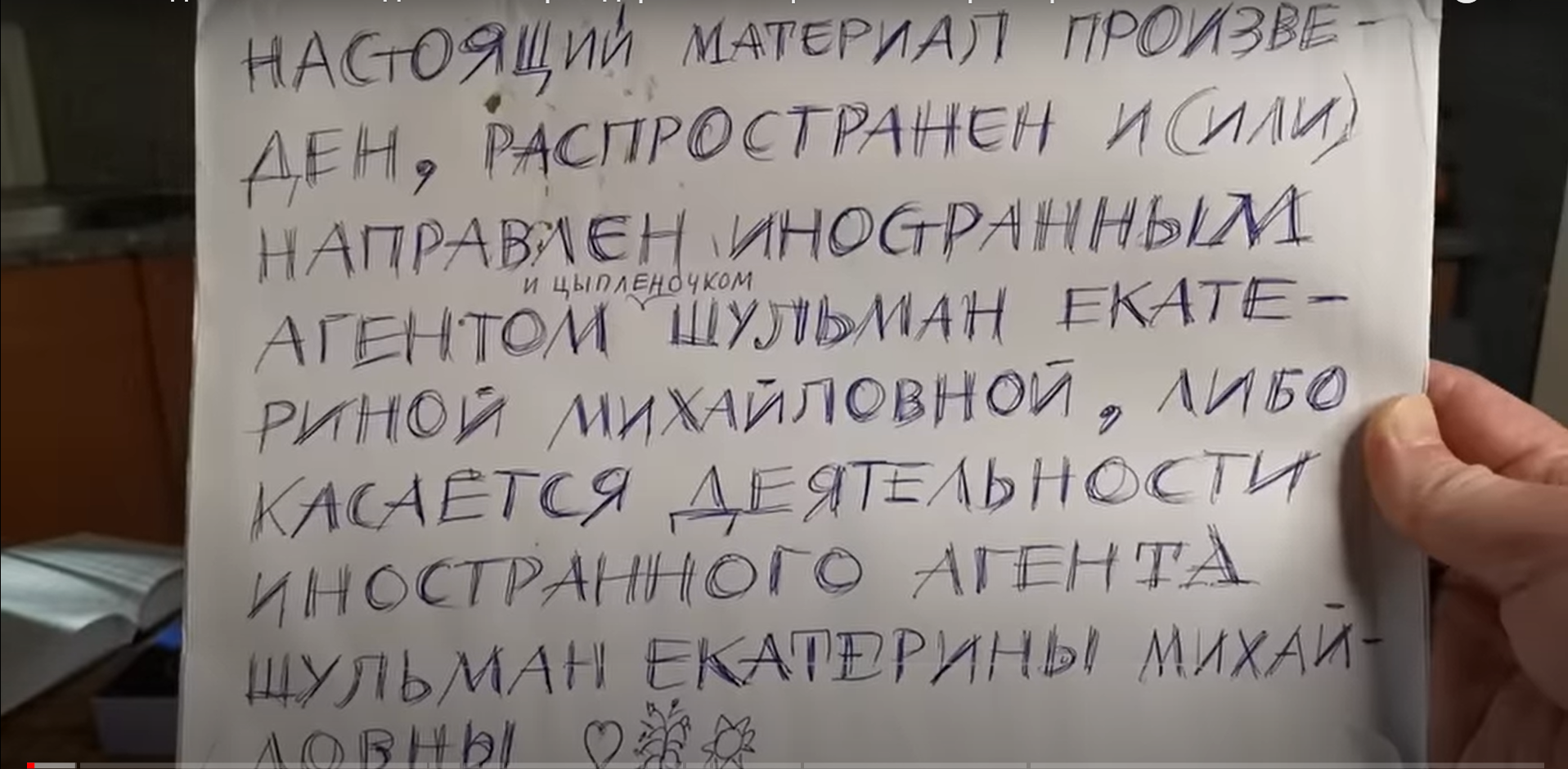

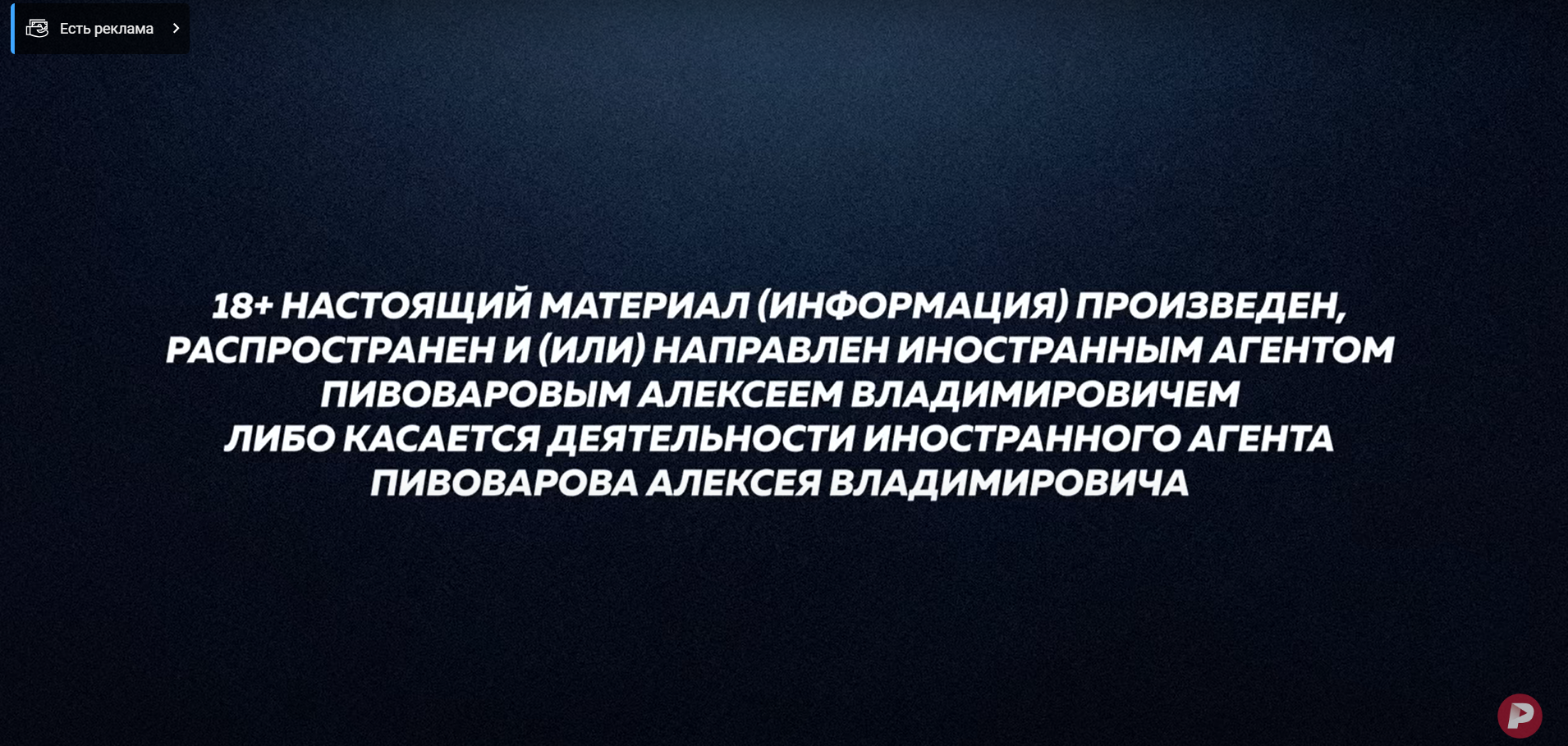

Formal requirements: labelling

Besides that the Russian Ministry of Justice requires people to use the label of ‘foreign agent’. So-called ‘foreign agents’ are required to label all their media and internet materials as well as appeals to the Russian authorities. Moreover, they have to inform shareholders, staff and beneficiaries about their status. The new law set uniform labelling rules for all of those who were placed in the registry. The new labelling form looks as follows: «Тhis material (information) has been produced, disseminated, and/or directed by a foreign agent (full name), or pertains to the activities of a foreign agent (full name). The labelling has to be written in Russian and placed at the beginning of the material, and the size of the font has to be twice as in the main body of the text. In audio and video materials the labelling (warning) has to last at least 15 seconds, be placed in the centre of the picture and occupy no less than 20% of the image area.

Not only do so-called foreign agents have to use the labelling, but other media that references materials from individuals listed in the registry as well should label their publications. The Centre for the Defence of the Rights of Journalists and the Media specifies that «the labelling should be present not only on the website but also in the social media accounts of the publication». It also underlines that any mention of ‘foreign agent’ in the media has to be accompanied by the warning of the status. The Roskomnadzor press service announced that «The editorial team of the media is entitled to independently determine the form and placement of such indications. This might be mentioning the status of a 'foreign agent' prior to their announcement on air.»

According to the new law, ‘foreign agents’ do not have to label all of their messages as in private chats and dating apps. The Ministry of Justice announced that ‘foreign agents’ have to label only content that is connected to their activities as ‘foreign agents’. «To avoid all these comical cases of everyday content on social networks… such incidents are excluded. It was suggested in the report that labelling [will be used] only for professional activities, or activities based on which a particular entity was recognized as a foreign agent», — BBC Russian Service cites Deputy Minister of Justice Oleg Sviridenko. At the same time ‘foreign agents’ are fined for the absence of labelling in personal posts: this happened with Ekaterina Shulman who was fined for the post about personal impressions of a stay in Berlin that was published without «foreign agent» labelling. Rapper Morgenstern was fined for three short posts where it was written 'hi', 'I uploaded some really nice photos on Insta, please take a look', and 'hooray! '.

During the hearing on the lawsuit for the liquidation of the Memorial Human Rights Centre, a representative of the Moscow prosecutor’s office stated that the absence of labelling in materials from 'foreign agents' could 'cause depressive states among citizens, ' as they 'cannot approach such materials critically'.

It is noteworthy that books published by 'foreign agents' are subject to stricter restrictions than other materials. They not only have to be labelled but also sold in packaging. Additionally, various printed materials are prohibited from being sold to children — they must be marked with an '18 ' sign.

A representative of the project, which has been listed in the registry and decided to use labelling, describes the experience of fulfilling this obligation as follows: 'The labelling looks and sounds absurd and humiliating. But paying fines and risking a criminal case afterward doesn’t seem reasonable. The arguments here have been known for a long time, but everyone weighs them differently. Weighing them when you are ready to break the law (because it is bad or for another reason) is a purely personal (or group) choice. For us, labelling is clearly not the case. The more significant problems from the status are not in this, but in the fact that others may be afraid to deal with a 'foreign agent.’

Mediazona also complied with the labelling requirement; however, after the outbreak of the war and blocking of the site, the 'badge' disappeared from the materials. The editor of the publication, Yegor Skovoroda, emphasised in a conversation with OVD-Info that Mediazona had been complying with all of the law and Roskomnadzor requirements for a long time: 'We wanted to continue working in Russia for as long as possible, without being blocked and staying within the legal framework.' According to the editor, Roskomnadzor had been complicating the publication’s activities even before it was included in the registry, sending various demands for the removal and correction of materials: 'All these demands were difficult and unpleasant even before the 'foreign agent' status. Fulfilling them took time and effort.' According to the journalist, the labelling had a negative impact on the publication’s work: views dropped on many social networks.

On 6th March 2022, following the start of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine, the Mediazona website was blocked. On 18th April 2022, the Mediazona announced their refusal to comply with labelling requirements. «At the start of the war, we made a decision not to play these games anymore. We are not going to replace the word 'war' with 'Roskomnadzor' (the shortened name of the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media) in square brackets or censor ourselves in any other way. Against this backdrop, it would be odd to apply any labels. Illogical, meaningless, and disrespectful to our readers, ” said Skovoroda. According to him, Sergey Smirnov, the chief editor of MediaZona, was fined several times for not complying with the publication’s labelling requirements.

People included in the registry as individuals also speak of refusing to label. For instance, Maxim Pokrovsky, the leader of the band 'Nogu Svelo', in a conversation with OVD-Info, noted that he does not label his publications: «I and our team consider this akin to acknowledging and accepting the unfair status that was assigned to me.»

Actress and former TV presenter Tatyana Lazareva told OVD-Info that she had initially used the label but later refused to continue doing so. «For me, it wasn’t technically challenging, but it was morally difficult. I am an emotional person, and each time I understood that by applying this label, I was going against myself. I don’t agree with it. I am not a ‘foreign agent’. I felt so disgusted and nauseated that I stopped writing on social media. Then I decided: I think I will write what I want, without looking back at these unpleasant feelings. So, I stopped using it [the label] on principle, ” says Lazareva.

In January 2022, the IT volunteer team of OVD-Info, in collaboration with the Voskho' agency, created a plugin for the Google Chrome browser that replaces the labels on media websites with advertisements for those organisations that signed the petition to repeal the law on ‘foreign agents.’

Sanctions for Violating the Requirements for ‘Foreign Agents’

Modification of Administrative Responsibility

Since 29th December 2022, all ‘foreign agents’ are subject to administrative responsibility under the same article — 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation («Violation of the Operating Procedures of a Foreign Agent»). Previously, there were five administrative articles with different sanctions for different types of ‘foreign agents.’

‘Foreign agents’ are held administratively accountable for violating any requirements established by law: absence of labelling, failure to provide or delay in submitting reports, refusal to establish a legal entity when listed in the registry, distorting or concealing information from the Ministry of Justice, and not disclosing their status while conducting activities. Additionally, punishment is provided for a person who is not yet included in the registry and conducts ‘foreign agent’ activities but has not reported this to the ministry.

For these violations, citizens face a fine of 30,000 to 50,000 rubles, officials — from 100,000 to 300,000 rubles, and legal entities — from 300,000 to 500,000 rubles. If the violators are foreigners or stateless persons, they can be expelled from Russia. In the case of unregistered public associations (for example, OVD-Info), individuals listed in the registry as participants of a ‘foreign agent’ are held accountable. The Ministry of Justice independently decides who to list as participants, and the law does not provide a mechanism for removing or modifying this entry, even if a person was included in the registry by mistake or has no further affiliation with the association.

According to the Ministry of Justice, in 2022, there were 156 protocols drawn up for administrative offences committed by ‘foreign agents.’ This is 2.7 times more than in 2021. In the first half of 2023, courts considered 72 cases under the new Article 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation, holding 58 individuals accountable, as per the data from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court. They were fined a total of 6.8 million rubles. As monitoring of court information by OVD-Info shows, in 2023, at least 412 cases were brought to court under Article 19.34 of the Administrative Offences Code.

Changes in criminal liability

‘Foreign agents’ are subjected to criminal liability by article 330.1 of the Russian Criminal Code. The new version of this article, which came into effect on 29th December 2022, standardised the punishment for all those included in the register — previously, different categories of ‘foreign agents’ were punished differently. Part 1 penalises a potential ‘foreign agent’ for evading the submission of documents required for inclusion in the register. Part 2 punishes those already included in the registry of ‘foreign agents’ for violating its obligations. A person may become a subject of a criminal case under Part 1 or 2 if they have already been brought to administrative liability under ‘foreign agency’ article 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation and have committed two more administrative offences within a following year.

Under part three of this article, criminal liability is applicable if a person purposefully collects information in the military field and fails to submit an application to the Ministry of Justice for inclusion in the register. Such cases are immediately considered a crime, even if it was not preceded by an administrative offence. The condition for prosecution under this part of article 330.1 is the potential of using such information against the national security of Russia. But this is an estimating criterion, so government agencies may interpret it at their will.

Offences under article 330.1 are punishable by a fine of 300,000 roubles (US$ 3,340 as of January 2024) or two years worth of income, by community service, correctional or compulsory labour, or by imprisonment for up to five years. Only individuals can be held criminally liable. If, in the opinion of the court, the law was violated by an organisation, its head or another person whose duties included fulfilling the corresponding ‘foreign agent’ requirements will be held accountable.

In early 2023, the first criminal case under the new version of Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code was opened in Tver’, a city in a European part of Russia, against Artem Vazhenkov, the former coordinator of independent election monitor organisation Golos’, «for repeated evasion of his duties as a ‘foreign agent’». He was arrested in absentia, but the case was later suspended while Vazhenkov remains wanted. In January and June 2022, the activist was fined twice under the ‘foreign agent’ article 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation. In January 2024, another criminal case under Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation against Vladimir Zhilinsky, the former coordinator of the city of Pskov branch of Golos’, also was reported.

In October 2023, Russia’s first case under Part 3 of Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code was initiated. Alsu Kurmasheva, editor of the Tatar-Bashkir service of Radio Liberty, was detained at Kazan airport while trying to fly to the Czech Republic, where she lives with her family. The journalist returned to Russia in mid-May for family matters. The investigation claims that Kurmasheva obtained information about teachers of a Tatarstan university who had been drafted into the army and used this data to compile analytics for international organisations, but did not voluntarily submit documents to the Ministry of Justice to include herself in the register of ‘foreign agents’. On 23rd October 2023, the court placed the journalist in custody.

Previously, the Criminal Code provided that a person who had already been included in the register as a ‘foreign agent’ collecting information in the military sphere could also be held criminally liable for the first violation of the requirement to submit information to the Ministry of Justice about the necessity to be included in the register. An individual ‘foreign agent’ conducting political activities on the territory of Russia in the interests of a foreign source could be held criminally liable for failure to submit an application for inclusion in the register only if they have previously been held administratively liable for a similar ‘offence’.

However, now a ‘foreign agent’ individual who collects information in the military sphere may face criminal punishment not only for failure to provide information, but also for any violation of the law on ‘foreign agents’ committed twice after the first ruling under Article 19.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences came into effect.

On top of that, the new wording expands the possibilities of criminal prosecution of the heads of ‘foreign agent’ NPOs and ‘foreign agents’ of non-registered public associations. While previously the heads of NPOs and unregistered public associations could only be held criminally liable for malicious evasion of their obligations to submit documents required for inclusion in the register, now for all foreign agents any repeated violation of the requirements of the ‘foreign agent’ legislation may be the cause of criminal prosecution.

Other penalties

After amendments to the law, the authorities may not only hold ‘foreign agents’ administratively and criminally accountable, but also block their websites or dissolve a legal entity or public association.

Blocking information resources

The website and other information resources of a ‘foreign agent’ can be blocked for any violation of the law on ‘foreign agents’. To do it, the Ministry of Justice sends a request to Roskomnadzor, which then blocks the resource. In part 1 of article 15.9 of the Law on information, it is specified that for this Roskomnadzor needs the court resolution on «foreign agent’s» administrative case that entered into force. However, in practice, the service immediately blocks the ‘foreign agent’s’ sites, even if there’s no court resolution.

In the summer 2023, Roskomnadzor at the Ministry of Justice request blocked websites of OVD-Info with legal instructions and news – ovd.legal и ovd.news, and also the project’s pages on «Odnoklassniki» and «Dzen». In Roskomnadzor’s email it was only indicated that the access is restricted based on part 4 article 12 of the ‘foreign agent’ law. In the Ministry of Justice it was reported to OVD-Info that sites were restricted for violating requirements regarding ‘foreign agent’ statements. The Ministry of Justice sends requests to block ‘foreign agent’ sites at their own discretion, without bothering to obtain a legally effective judgement. In January 2024, the Zamoskvoretsky District Court of Moscow recognized the blocking of OVD-Info’s information resources as legal.

In the same way, information resources of other ‘foreign agents’ were blocked: for example, Dmitry Davidov’s project «20 ideas», as well as «Academia» and «Boulevard of Gordon» by Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon.

Legal entity’s liquidation

The Ministry of Justice can file a lawsuit to the court seeking the liquidation of a ‘foreign agent’ legal entity or unincorporated organisation if a ‘foreign agent’ has repeatedly violated information requirements: did not disclose their status while engaging in ‘foreign agent’ activities, did not put the ‘foreign agent’ sign, did not submit statements or violated requirements for it.

The government has used a forced liquidation mechanism against ‘foreign agent’ legal entities before: International public organisation «Memorial» and the Human rights centre «Memorial», Chelyabinsk fund «For Nature» and other organisations were liquidated for violating the ‘foreign agent’ law.

New formal restrictions for ‘foreign agents’

Vladimir Putin often compares the Russian ‘foreign agent’ law with the American one, describing the domestic counterpart as «more liberal» and «lenient». According to his words, a ‘foreign agent’ in Russia — «is a person who engages in public activities for the money of a foreign government». The president contends that the law «doesn’t even prohibit him [„foreign agent“] from engaging in this activity», but simply requires the disclosure of funding sources.

The 18 organisations for ‘foreign agents’ established by the law indicate the opposite. Authorities banned ‘foreign agents’ from organising protests, becoming observers for elections, teaching in schools and universities, receiving state funding and much more. After the adoption of the new ‘foreign influence’ law, the list of restrictions grew.

Restrictions related to elections

Officials introduced the majority of such restrictions back in 2021. According to them, all categories of ‘foreign agents’ are prohibited from participation in agitation for or against candidates, and also in election campaigns — including the donation of money. Beside that, ‘foreign agents’ can not be trusted representatives of candidates and electoral associations. These restrictions were transitioned into the new law — we already covered them in the previous version of the report.

At that time, the Venice commission experts noted the uncertainty that these restrictions, in fact, prohibit covering elections for media entities included in the registry of ‘foreign agents’. In order to understand the issue, special clarification from the Central Election Commission wes required, which once again emphasised the uncertainty of the legislation. As a result, CEC allowed ‘foreign agents’ media entities to cover elections.

However, in practice election commissions may not listen to the CEC’s explanation. So, in 2022, in the eve of the early mayoral elections in Rybinsk, the regional election commission revoked accreditations from two journalists — Vladimir Egorov, the editor-in-chief of the news agency »Vremya», and freelance correspondent Polina Kostyleva. In the commission it was declared that Egorov and Kostyleva did not indicate they were included in the ‘foreign agents’ registry when submitting documents. Journalists appealed the decision and reached the First Appellate Court. As a result, the court sided with them — the denial of accreditation due to their ‘foreign agents’ status was recognized as a violation.

In 2021, the electoral legislation introduced the concept of «affiliation» with a foreign agent through expanded criteria. Thus recognizing the connection of any candidate to a ‘foreign agent’ within two years before elections are appointed and during the election campaign.

Such candidates, as well as ‘foreign agents’ themselves, must indicate their status in payment documents if they are making donations to the election fund, as well as information about the connection with ‘foreign agents’ in election documents. In 2022, these restrictions were transferred to the law on «foreign influence», more details about them — in the last version of the report.

The legislation on ‘foreign agents’ also restricted election monitoring by recognizing this activity as political. Now, ‘foreign agents’ are not allowed to be election observers: in June 2023, the Supreme Court confirmed this.

Participants of Golos’ (Voice in Russian), a movement in defence of voters' rights, whose work is directly related to election monitoring, called the entire law on ‘foreign agents’ discriminatory. «[The law] infringes on the right of foreign agents to monitor the integrity of elections, while from the point of view of the Constitutional Court, the ability to monitor is part of the active electoral right,» the Movement wrote after the Supreme Court’s statement.

Golos’ itself has been prosecuted under the ‘foreign agent’ legislation since 2013: at that time, the court fined the association 300,000 roubles because its members had not applied for inclusion in the register of ‘foreign agents’. As a reason, they used the monetary part of the Helsinki Committee award; however, the association did not accept the money. In 2014, the Ministry of Justice forcibly included Golos’ in the register of ‘foreign agents’, and although later the court cancelled this decision, the ministry officials still did not exclude the project from the list. In 2015, the Golos Foundation for Democracy was recognised as a ‘foreign agent’. In 2016, the court ruled to liquidate the association at the behest of the Ministry of Justice; Golos’ continued to operate as an unregistered organisation. But in 2021, it was included in the ‘foreign agents’ register. In addition, 18 regional coordinators of Golos’, three council members and two regional branches (Samara and Golos-Ural) were also included in the list of ‘foreign agents’.

After the adoption of the new law, Golos’ noted that the ban on election monitoring would hit only people who were recognised as ‘foreign agents’ in their personal capacity. «As for citizens' associations like Golos’, they have not been able to send observers to polling stations before — regardless of whether or not they have foreign agent status. Only political parties, candidates and public chambers have had this right for many years. But this did not prevent the organisation of independent monitoring during the elections,» the activists wrote.

Financial limitations

Prior to the adoption of the new law, ‘foreign agents’ were often denied subsidies: For this purpose, the authorities used the status of Non-Political Organisations (NPO)-"performers of useful services», which were entitled to «priority support measures». At the same time, only NPOs «not performing the functions of a ‘foreign agent’» could be «performers of useful services». In addition, similar restrictions for ‘foreign agents’ were prescribed in the terms and conditions of regional and municipal tenders for subsidies. We spoke about this in more detail in our previous report.

In 2022, the norm that ‘foreign agents’ cannot receive state support was added to the law. «Providing assistance to ‘foreign agents’ from the state contradicts national interests and common sense,» said State Duma deputy Andrei Alshevskikh at one of the meetings. In April 2023, the official and his colleagues from the Duma commission decided to supplement this restriction: they proposed prohibiting ‘foreign agents’ from receiving financial and property support from the state.

One of the authors of the initiative, Olga Zanko, deputy chairman of the State Duma Committee for the Development of Civil Society, said that property support is «a serious help for NPOs; it is wrong to give it to those who work against Russia’s interests». In July 2023, Putin signed the law depriving ‘foreign agents’ of property support from the state.

Back in January 2023, ahead of the State Duma deputies, the Moscow City Property Department announced the termination of lease agreements for all premises of the Sakharov Centre — the main building, the exhibition hall and the flat. «The reason for the eviction is the amendments to the law on ‘foreign agents’ that came into force on the first of December last year. According to these innovations, ‘foreign agents’ should not receive any state support. All the premises of the Centre were rented from the city free of charge,» the Sakharov Centre staff wrote.

In addition to this, «foreign agents» face other financial restrictions:

- ‘Foreign agents’ cannot insure bank deposits. This does not apply to individuals, including individual entrepreneurs.

- They cannot use a simplified tax system and simplified accounting methods. One of the initiative’s authors, State Duma deputy Vasily Piskarev, explained the amendment as follows: «We consider it wrong to provide any privileges to individuals and organisations that promote the interests of foreign states in our country, and more often than not, unfriendly to us.»

- It is prohibited to invest in economic entities that are strategically important for ensuring the defence and security of the state. The activities of such entities, in particular, relate to the defence and nuclear industry of the country.

Restrictions on monitoring government actions

In 2019, NGOs labelled as ‘foreign agents’ were prohibited from nominating candidates for public oversight commissions protecting human rights in places of detention. In 2022, this restriction, along with others, was incorporated into the new law on ‘foreign agents.’

Speaking about this prohibition in December 2020 during a meeting of the Human Rights Council, Vladimir Putin stated that he «cannot imagine foreign agents in the U.S. coming and demanding to be admitted to the public council of the State Department.» Following the same logic, the Ministry of Health prohibited NGOs from the ‘foreign agent’ registry from nominating candidates to the existing Council for Public Organizations for Patient Rights under the ministry. Details can be found in the previous version of the report.

Since 2018, non-profit organisations labelled as ‘foreign agents’ are prohibited from conducting independent anti-corruption expertise of regulatory legal acts or their drafts. Ilya Shumanov, executive director of Transparency International — Russia, an anti-corruption organisation, emphasized that this tool has «no substantive meaning for civil society or the expert community» since, according to the law, such expertise only has a recommendatory status. «If we talk about the content of the initiative, we immediately recall a phrase from a great TV series: „what is dead may never die“. This is just about the very independent anti-corruption expertise in Russia,» Shumanov said.

‘Foreign agents’ are not allowed to act as experts in conducting state environmental expertise, as well as participate in organising and conducting public environmental expertise. During the discussion of this amendment in the State Duma, the focus was mainly on the «benefit» of this decision not for the country’s ecology but for the economy. For instance, one of its authors, United Russia member Alexander Kogan, stated that it is a «timely initiative» that «protects our economy.» Deputy Dmitry Vyatkin supported him and added that international environmental funds, including «foreign agents,» released reports on the environmental situation in Russia, negatively impacting the country’s economic development, so allowing them to conduct environmental expertise is not acceptable.

Other restrictions

Even before the adoption of the new law, «foreign agents» were prohibited from holding positions in state authorities and local self-government bodies. This discriminatory restriction still exists today, directly contradicting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Both documents emphasize that every person has the right to enter public service in their country.

Due to the status of ‘foreign agent, ’ access to state secrets may be denied: this prohibition was introduced in 2021 and transferred to the new law. In December 2022, a court removed lawyer Mikhail Benyash from participating in the case of former Rosgvardia officers who refused to go to war in Ukraine because Benyash was included in the ‘foreign agent’ registry. The lawyer noted that he had participated in the case from the very beginning, so he had already reviewed classified materials before being included in the registry. «I am already familiar with the 'secret.' And I don’t know how they will make me forget something. I don’t know such legal instruments. Lobotomy, perhaps?» Benyash speculated.

A ‘foreign agent’ cannot be the organiser of a rally. In addition, citizens are prohibited from receiving money and «other property» from ‘foreign agents’ to conduct public events. Co-author of the initiative, United Russia deputy Maria Butina, stated that the ban on organising rallies by «foreign agents» is necessary to prevent protests «on foreign funds.»

Since December 2022, authorities have prohibited ‘foreign agents’ from producing information products for minors: now all materials—printed and digital—must be labelled «18 .»

In September, filmmaker and blogger from Yaroslavl Andrey Alexeev was fined 30,000 rubles: his YouTube videos were not age restricted. Alexeev was found guilty of violating foreign agent restrictions (Art. 19.34, p. 8 of the Code on Administrative Offences). In court, the blogger tried to prove the absurdity of the incriminated offence. «Our arguments that the damages of this unintended action were fairly insignificant while the entirety of my real audience, according to the statistics, are over 18 were expectedly ignored by Judge Bekenev,» wrote Alexeev in his Telegram channel.

In some regions, the desire to shield minors from ‘the influence of foreign agents’ has reached a point where libraries give out books by ‘foreign agents’ only upon presentation of ID. Such cases occurred in the libraries of Krasnoyarsk and Omsk: their employees referred to the age limit of 18 and asked to show a passport.

According to the new law, ‘foreign agents’ are banned from educational work with children. The Ministry of Education proposed the ban as early as April 2021. In the explanatory note, officials claimed the law effective at that moment created «the preconditions for the uncontrolled implementation of a wide range of propaganda activities by anti-Russian forces in schools and universities under the guise of educational work.»

The following year, a bill completely prohibiting ‘foreign agents’ from conducting teaching work, as well as engaging in educational activities, was introduced to the State Duma. Subsequently, these restrictions were included in the new law on ‘foreign influence’; several people have already been affected by them:

- Moscow politician Yulia Galyamina was fired from The Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) almost immediately after the law took effect — in December 2022. The Academy’s management referred to the new restrictions for ‘foreign agents’. The politician appealed the decision in court and demanded to reinstate her as an associate professor. «I don’t have any special grievances about RANEPA: my question is about the law on ‘foreign agents’ which violates people’s constitutional rights to have their own opinion, which is also actually guaranteed by the Constitution, ” wrote Galyamina.

In August 2023, the court sided with the politician: RANEPA was compelled to reinstate Galymina as an associate professor and pay her 115,000 rubles for forced absences and moral damages. However, she was fired again after this: „Not a day passed between my reinstatement and eventual dismissal. The orders were signed on the same day, ” noted Galyamina, adding she had no intention of giving up. - In July, 2023, politician and lecturer Mikhail Lobanov was fired from Moscow State University (MSU) for his status as a ‘foreign agent.’ Before that, he wrote that he had been asked by MSU’s rector Viktor Sadovnichy to quit. „The university was faced with an ultimatum: either you fire Lobanov or MSU suffers, ” said the lecturer. The formal basis was the actual ban on teaching activity for ‘foreign agents’ under the legislation updated in 2022.

In October, the court refused to reinstate Lobanov as a lecturer at MSU. In court, the university admitted it violated the labour law, but it based it on the fact that, according to the law on ‘foreign agents’, it cannot provide support persons included in the register in the form of salary payments. „We consider this approach misguided and illegal as compensation for labour has nothing in common with state support. We will submit an appeal, ” commented lawyer Maksim Olenichev.

Requirements and risks while interacting with «foreign agents» and disseminating information about them

Third party liability

In 2023, Russia introduced third party liability for helping ‘foreign agents’ circumvent the restrictions that the status imposes. Now authorities, citizens and organisations must ensure their actions or inactions don’t help ‘foreign agents’ break the law.

This concerns all individuals regardless of their citizenship or lack thereof, public authorities, organisations of all forms of ownership and their officials.

If a report about such a violation is received, regulatory bodies could arrange an unscheduled inspection. Firstly, a warning would be issued for aiding a ‘foreign agent’ in circumvention of the limitations of the law. Not less than one month is given for the remediation of the violation. If the assistance continues, the violator faces liability under section 42 of Article 19.5 of the Code of Administrative Offences. Penalties are quite high: between 30,000 rubles (US$334) and 50,000 rubles (US$557) for individuals, between 70,000 rubles (US$780) and 100,000 rubles (US$1114), or disqualification for up to two years for officials, between 200,000 rubles (US$2228) and 300,000 rubles (US$3342) for legal entities.

Circumvention of restrictions that helpers may be held accountable for is listed in Article 11 of the new law. They cover the whole spectrum of different actions from the organisation of public events and educational activities towards minors to conducting ecological examinations. Hiring a foreign agent as a teacher, an invitation as an expert to the university or school, publishing and selling books by a foreign agent without the marking «18 „, and so on can be considered assistance. As of January 2024, there is no information on the cases of anyone being held accountable for assisting foreign agents to circumvent the restrictions.

To sum up, individuals and officials are forced to stop any interaction with people or organisations that are added to the register of foreign agents at the risk of significant fines. The deliberately unclear formulation of the law suggests that people would avoid any cooperation with ‘foreign agents’, even the one that is not harmful de jure.

Responsibility for Non-Marking and Other Formal Risks

The Media Law prohibits registered media from mentioning ‘foreign agents’ or spreading their materials in publications, TV broadcasts, websites, and social media without acknowledging their status. There are fines and possible confiscation of the «violation of the law» object. Practice shows that there may be other consequences for the absence of the marking.

Fines could be imposed under sections 2.1 and 2.4 of Article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offences before the new law about «foreign agents» had taken effect. Under section 2.1: in the case of mentioning or creation of a publication together with the NPO-’foreign agent’. Under section 2.4: in the case of republication of the material by the media- ‘foreign agent’.

There were several registers of ‘foreign agents’ before December 2022 that were updated frequently. It complicated adherence to marking requirements. Mass media were compelled to track the changes in all registers and take them into account in all their materials where NPOs, media, and people who turned out to be ‘foreign agents’ are mentioned.

Upon the introduction of the unified register of ‘foreign agents, ’ section 2.4 lost its legal force, while section 2.1 of Article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offences was updated. NPOs- ‘foreign agents’ were replaced by ‘foreign agents’ meaning all the groups. The maximum fine for individuals for mentioning ‘foreign agents’ without marking is 2,500 rubles (US$28), for officials 5,000 rubles (US$56), and for legal entities 50,000 rubles (US$557).

At the same time, mass media still must track the changes in the register and consider the updates in all their materials. However, it does not always help to avoid the fine. In October 2023, the founder of the EVENT LINE publisher was fined 40,000 rubles (US$446). Journalists mentioned rapper Noize MC, Ivan Alexeev, who is added to the register of ‘foreign agents’ under his real name on the website without mentioning his status. The defence attorney during the trial argued that, although the editorial board is proofreading texts for mentions of ‘foreign agents’, the publisher «neither has the knowledge nor resources to compare all the nicknames (trademarks) and corresponding people that may be on the list of ‘foreign agents’».

Possibly, because of this and similar cases, the Ministry of Justice decided to include aliases of individuals and add information about former names, surnames, and patronymics in the register of ‘foreign agents’.

For non-marking of ‘foreign agents’ in the media, consequences can follow:

- Arrest of property

In December 2021, Pyotr Kanayev, the chief editor of RBC, was fined 4,000 rubles (US$45). He was charged with section 2.1 of Article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offences. The reason for the act was a publication on the RBC website with a mention of the Information and Analytical Centre «Sova» without the «foreign agent» marking. Kanayev did not pay the fine on time, which resulted in a penalty of 1,000 rubles (US$11).

Because of this debt of 5,000 rubles in March 2023, bailiffs seized the property of RBC’s editor-in-chief — an apartment in Stupino district and a dacha. «I received a letter from the bailiffs with a notice of property arrest this morning via Gosuslugi (The Federal State Information System „Unified Portal of State and Municipal Services (Functions)“). There are quite a lot of such fines coming in all the time, I might have missed one. Usually they are automatically deducted from your salary. But the decision to arrest my apartment and dacha because of a debt of five thousand rubles from the point of view of proportionality of the scale of the violation and the punishment that followed, I consider inexplicably excessive,» said Kanaev. - Liquidation of a media website

In 2022, Roskomnadzor (the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media) issued two warnings to Novaya Gazeta: the publication’s journalists mentioned «Civic Assistance» and «Humanitarian Action» in two articles without ‘foreign agent’ labelling. Because of this, the publication suspended its work. Subsequently, the supervisory agency demanded the liquidation of Novaya Gazeta’s website because of these unlabeled articles. In its lawsuit, Roskomnadzor referred to Article 16 of the law «On Mass Media»: according to it, «repeated violations within 12 months», for which warnings were issued, can become a reason for the termination of the media outlet through the court.

On September 9th, 2022, the Ministry of Justice removed «Humanitarian Action» from the register of ‘foreign agents’ — the organisation had been seeking this through the courts for several years. On September 15th, 2022, the Supreme Court ruled to liquidate Novaya Gazeta’s website following a lawsuit filed by Roskomnadzor. «Our lawsuit is aimed at protecting consumer rights,» representatives of the agency said in court. In the case of Novaya, it can be concluded that the authorities used «foreign-agency» legislation to put pressure on an independent publication. - Pressure on the hosting company and shutting down the site

In April and May 2022, Pavel Sofronov, editor-in-chief of the registered publication AllRusNews, was summarily fined 4,000 rubles: in his publications on the portal’s website, he failed to indicate that the OVD-Info and the Memorial Human Rights Center mentioned in the text were recognized as ‘foreign agents’. The editor became aware of the fines in December 2022, when Roskomnadzor sent him a demand to pay the debts.

At that time, Sofronov stated that he was not going to pay the fines and considered the administrative cases to be illegitimate. After that, Roskomnadzor twice demanded that the publication comply with court decisions and threatened it with an article on failure to pay a fine on time (part 1 of Article 20.25 of the Code of Administrative Offences), which provides for administrative arrest for up to 15 days.Subsequently, the All Rus News portal stopped functioning: the publication’s employees believe that this is due to previous messages from Roskomnadzor and the authorities' pressure on the provider with whom they had been working for six years. «Suddenly the site was inaccessible and the hosting account was blocked without any notification. Support did not respond either, and then reported that the server was blocked due to some complaint, but repeated requests to provide this very complaint were simply ignored by them,» the publication’s Telegram channel wrote.

The requirements to mention status apply only to publications registered as mass media or to ‘foreign agents’ themselves. However, the complex structure of legislation in this area leads social network users to start adding labels to their publications just in case: it is easier than figuring out when such warnings are really necessary.

Indirect consequences

Representatives of the Russian authorities often speak in a hostile manner about ‘foreign agents’ and call for a fight against their activities, creating an atmosphere of hatred or at least distrust towards ‘foreign agents’

According to the results of a poll conducted by RPORC (Russian Public Opinion Research Center) in 2023, Russians perceive the phrase ‘foreign agent’ negatively. Here are the associations with this term that emerged among respondents: a negative attitude (20% of respondents), a traitor to the Motherland (18%), a spy (9%), an enemy of the people (5%), someone who is acting against Russia (5%), in the interests of another state (3%). The share of respondents who have such associations has grown over the year. Only 2% of Russians express a good attitude to ‘foreign agents’. The perception of ‘foreign agents’ has changed over the year: the abstract variant ‘spy’ has become less frequent, but the perception of ‘foreign agents’ as traitors to the Motherland has increased. A variant that had not been heard before — «those who left the country» — also appeared.

According to the poll by «Levada-centre», conducted at the end of 2022, the majority of respondents (45%) considers the law on ‘foreign agents’ to be necessary to limit Western influence on Russia. About one-third of the respondents (30%) see this law as a way for the authorities to oppress independent non-governmental organisations. Half of the respondents affirm that their attitude towards a non-commercial organisation, a politician or a mass-media outlet will not change if those get the status of a ‘foreign agent’. A third of the respondents state that their attitude will become more negative. In July 2021, 58% of the respondents supported a neutral position, and 26% supported the negative one.

In the last two years, trust towards organisations with the status of ‘foreign agents’ as well as the will to give them public and financial support has decreased. ‘Foreign agents’ face declines in their funding from crowdfunding, rejections to cooperate and even to mention them which also contributes to the decrease in donations or in visiting partner’s links. Russian organisations and individual entrepreneurs are often unwilling to provide any services or to lend premises to ‘foreign agents’; some lawyers refuse to grant legal help to third parties if it is sponsored by a ‘foreign agent’.

The ‘foreign agent’ status hinders the spread of information and reaching a new audience, since other persons are reluctant to cite or publish any ‘foreign agent’s message for the fear of being included in the list of ‘foreign agents’ themselves.

«After I was listed [as a ‘foreign agent’], the number of people from Russia willing to collaborate with me has declined», — notes Tatyana Lazareva. «I have my own YouTube-channel, and it has already been three or four times when people who support my position but currently reside in Russia refused to work with me. They explained that they couldn’t do it due to unfinished projects there [in Russia]. They are afraid of losing them, thus, they do not want to appear on a ‘foreign agent’s’ channel.»

Maxim Pokrovsky also mentions the difficulties he faced after obtaining the status: «Anytime some limitations are imposed, when they are imposed unjustly, it’s always unpleasant. Yes, this status has led to financial losses. We lost an important project for children related to ecology. Additionally, I’ve lost all the opportunities to licence music in Russian cinema. And I don’t even mention the issue of concerts.»

Representatives of NGOs with ‘foreign agent’ status say that authorities are often hostile towards applications that ‘foreign agents’ send for public interest because of the negative associations this status possesses. ‘Foreign agents’ are considered as spies and traitors. This negatively affects, inter alia, human rights activism. Moreover, the status of ‘foreign agent’ worsens the mental state of many people who are on the list or who collaborate with organisations ‘foreign agents’. A lot of ‘foreign agents’ voice their disagreement, their anger, irritation and grief caused by the decision of authorities, but at the same time intend to continue their activity and to fight further.

«My first reaction — in a shaky voice I say to Mitya something like „I’m a ‘foreign agent’“ and start crying. Bitterly. Yes, like this. Because when this happens to you, it’s not funny at all. It hurts and it is painful. For I am not my State’s enemy. Apparently, the State still can hurt me. …> The Law on Foreign Agents is insulting, and its application is a shame. If someone above wants us to break — they will not see it, ” this is how lawyer Valeria Vetoshkina described her reaction to the Ministry of Justice’s decision to consider her a ‘foreign agent’.

Sometimes the status of ‘foreign agent’ is ironically called an «acknowledgement» or an «award». The actress Tatyana Lazareva described her attitude towards this point of view: «[When I’d been included in the list], everyone congratulated me in a usual way and told me that I enjoy a great company. They added that today it’s become an honour and almost an order. Well, to be honest, in this situation I wonder, why do I need an order? I’ll accept the medal, as it’s in one quote. I don’t need such orders by any means. For me, it’s very insulting since I don’t deserve such a status at all. That’s why I’m trying to challenge it in any possible legal way.»

The musician Max Pokrovsky has the same opinion: «Most of my subscribers received this [the status of ‘foreign agent’] very well, and I’m even sorry to disappoint them with the fact that my attitude is totally different. I don’t need any „acknowledgment of my achievements“ from the authorities in today’s Russia. Only a few people expressed their regrets, understanding that this status results in all possible kinds of limitations.»

The implemented policy on ‘foreign agents’ contributed to the rise of forced immigration cases. According to BBC News Russian, by the beginning of 2022 almost half the people designated in Russia as «international media functioning as foreign agents» either left Russia or are preparing to immigrate. There was an increase of ‘foreign agents’ leaving the country after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Conclusion

«There are no caveats, hidden agenda or foul play„ was the State Duma’s proclamation in regards to the status of ‘foreign agent’ being introduced into legislation for non-governmental organisations operating in Russia; in 2012 they assured people that such status wouldn’t impede an organisation’s conduct. After 11 years, NGOs labelled as ‘foreign agents’ are routinely accused of working for foreign intelligence agencies. Russian State Duma deputy and the bill’s co-author Andrey Lugovoy accused ‘foreign agents’ of seeking to destroy Russia from within, calling them latent traitors, berating them for being barking echoes of the collective West and broadcasting anti-national sentiment in national language en masse.

There was a conscious effort from the law-makers to use vague wording in the document, as they argued that specificity and restraint would only harm Russia’s safety and sovereignty and the bill’s effectiveness in monitoring the sources of foreign interference. That in turn makes these legislative norms malleable for interpretation and convenient for the government officials to wield as leverage.

The new law enabled more ways of going after ‘foreign agents’. As the unification of administrative liability simplifies the procedure of issuing and imposing fines, the criminal prosecution became a palpable threat to everyone with the aforementioned status. We’d argue that the «under foreign influence„ law is a freedom-suppressing tool that can at a moment’s notice swiftly become wide-spread.

After the beginning of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities increasingly referred to the ‘foreign agent’ legislations as a way to target alternative voices that don’t comply with the governmentally held views, even on topics that don’t directly tie into foreign policy. The ‘foreign agent’ status was given out to people with anti-war stances, LGBTQ people, ecologists and various other organisations and individuals that the authorities consider unacceptable. Being included in the registry of ‘foreign agents’ complicates the process of operating an NGO, leading to a lot of important projects shutting down: the artificially heightened standard for the accountability of financial statements and the likelihood of any help requests being denied on the basis of the ‘foreign agent’ status forces NGOs to be liquidated as a legal entity and stop their work.

OVD-Info and other human rights advocacy groups consider that the ‘foreign agent’ law is repressive and targets those who actively voice opinions non-compliant with the state policy and fight for their rights. This law should be retracted. This is an opinion shared by international institutions, who on numerous occasions urged the Russian government to repeal the law.

The state officials ignore the critics of the law and continue to make the norms and legislations targeting ‘foreign agents’ even more draconian. For example, a recent proposition from the Russian State Duma officials was to impose an obligation on ‘foreign agents’ to provide, in addition to their own financial statements, the financial statements and documentation on acquired property from their family members. State Duma deputy Andrey Lugovoy, after a year of the law being implemented, is head-strong about the necessity of escalating the law’s repressive measures against ‘foreign agents’. He equates being a ‘foreign agent’ to «betraying one’s country„ which is „the worst sin of all„. On his social media he blatantly posts statements encouraging people to harass ‘foreign agents’, arguing that such people remaining in Russia play a key role in the country’s upheaval. Lugovoy posits that shutting down „anti-national liberals„ is the key to quickly winning a „proxy-war„ and preventing the formation of a „second battlefront„.

Despite that, human rights activists continue to fight against this repressive tool. OVD-Info together with human rights advocacy groups Pervy Otdel (Department One), Russian LGBT Network, Public Verdict and other lawyers have sent a complaint to the United Nations Human Rights Committee: in it we outlined how the complainants have acquired the ‘foreign agent’ status and what kind of pressure and targeted harassment has been incurred after being included in the ‘foreign agent’ list. We encourage people to appeal to the courts against being labelled as a ‘foreign agent’. This is a way for people in the ‘foreign agent’ registry to voice their disagreement with the legislature imposed on them and showcase the will to fight for their rights. Legal justification for such complaints and international institutions’ condemnations is the basis for changing the legal system in the future. By continuing to talk about the absurdity and unlawfulness of this law, we’re standing against normalising repressions. We won’t be silent while the government is violating human rights. Civil society’s active protest against the ‘foreign agent’ law has already formed social connections that will help build a democratic constitutional state in Russia, where human rights will truly be of the highest value.