Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code on discrediting the armed forces, introduced in March of 2022, is a popular tool in fighting those protesting against the war. But experience has shown that judges often side with the citizens accused of violating it. We try to explain why that might be.

On April 8, 2022, a St. Petersburg resident named Vadim Dudarev conducted a one-person protest at St. Isaac’s Cathedral. He had two posters with him; one said, «The icons are crying for PEACE, ” and the other, «And now you try.» Mr. Dudarev recalls, «in about 20 minutes, a Road Patrol Service squad noticed me. They made a weird move: they drove away from me and then returned. Maybe this was their way of giving me a way out.»

On the way to the police station, one of the officers expressed his support to the protester, shook his hand, and recommended using Article 51 of the Constitution as his defense, which refers to the right not to be a witness against oneself. After completing the paperwork, a few officers came up to Mr. Dudarev with questions about his beliefs. They also asked him to take off and show his scarf.

According to Mr. Dudarev, he wore a «Swedish junior hockey league scarf that was yellow and blue; this color combination caused the police officers fits of paranoia. About four people wanted to see it; they took photos. I emphasized that the scarf had ‘Sverige’ written on it, which means ‘Sweden’ in Swedish.»

Then another officer entered the premises; he had adjusted his uniform to make it clear he was carrying a firearm.

«I had a highly unpleasant conversation with him. From what I could understand, he was part of the criminal investigation department; he did not introduce himself or disclose his title. He may have been an FSB officer. Upon my request to introduce himself he used the name Maksim, but I am not sure if that was his real name. He constantly switched between being friendly, threatening me, and shaming me. I invoked Article 51 (the article of the Russian constitution stating that no one shall be obliged to give evidence against themselves), following the advice of one of the officers, “ states Mr. Dudarev.

After 30 minutes, the officers released Mr. Dudarev into the lobby of the police station. Then ‘Maksim’ demanded to see his phone, but the detainee refused to give it up. Then the officer took down the phone’s IMEI, supposedly to verify that it was not a stolen device. Soon after, the police chief arrived; he drew up a report against Mr. Dudarev and asked him to write an explanatory letter.

According to the detainee, the officers debated whether to draw up a report under Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code or under the regional St. Petersburg law regarding Covid restrictions. Mr. Dudarev thinks they chose Article 20.3.3 due to the color of his scarf.

A protest fighting tool

Article 20.3.3 may be used against people, for example, for damaging posters with the letter Z or any other patriotic symbols, posting on social media, public speeches, private conversations or, like in Mr. Dudarev’s case, for anti-war protests or any other type of protest actions, as well as for items/signs that resemble Ukrainian or anti-war symbols.

Private individuals may be fined up to 50,000 rubles (US$ 715), officials — up to 200,000 rubles (US$ 2,860), and legal entities — up to 500,000 rubles (US$ 7,150). If the act of discrediting the armed forces is accompanied by a call for public action or creates a situation that poses «danger to public safety, ” the fine could reach 1,000,000 rubles (US$ 14,303) for legal entities, 500,000 rubles for officials, and 200,000 rubles for private individuals.

For example, the following items or actions have been qualified as discreditation of the army under Article 20.3.3: a poster, which read «Fascism Won’t Do», putting the words «special operation» in quotates, liking an anti-war video on «Odnoklassniki» social networkand a sheet of paper with asterisks instead of letters.

If a repeat offense is committed within the same year and while the first administrative penalty under Article 20.3.3 is in effect, the offender is in danger of being charged under Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code (public actions directed at discrediting the armed forces of the Russian Federation; punishable by up to five years in prison). Article 280.3 also has Part 2, i.e, if the «criminal discreditation» has led to severe consequences. Unlike Part 1, Part 2 can be applied without there being previous administrative chargers under Article 20.3.3. There is also another article, which provides for even harsher punishment of up to 15 years of jail time, namely, Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code for «fakes» about the armed forces.

Criminal cases for «fakes» are launched for practically any statements that go against the Russian authorities’ narrative regarding the war. Which article to use in any given case — 207.3 of the Criminal Code or 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code — is decided by law-enforcement services. There are examples of Article 20.3.3 being applied for destroying street structures with the letter Z, while criminal charges are laid for displaying some stickers or for social media posts with a negligible number of views.

By the middle of October 2022, Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code had brought in more than 85 million rubles in fines. According to OVD-Info data, as of the middle of August 2022, the average fine under Article 20.3.3 was 33,883 rubles (US$ 484).

Every week, there are new instances of this administrative article being used against people in cities as well as in remote communities all over Russia. According to the data analyzed at the end of November, we know of 5,159 cases launched for discrediting the army.

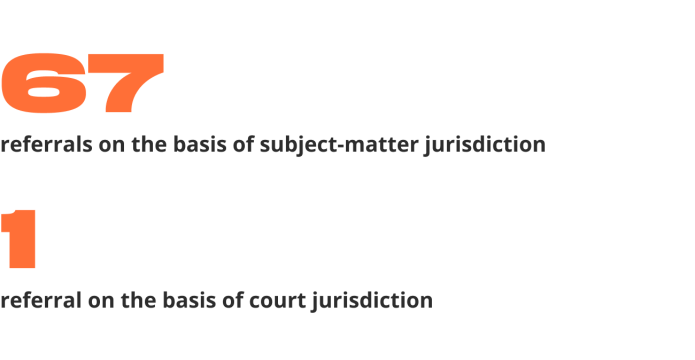

The courts do not always agree with police reports. Using court statistics, «Mediazona» has determined that 127 administrative cases have been dismissed, while 409 were returned to the police.

This means that in every ninth case under Article 20.3.3, the court rules in favor of the accused; cases returned to the police allow the accused to avoid an administrative penalty.

What the judges write

OVD-Info has gone through several dozen rulings on Article 20.3.3 cases from different regions that were issued in favor of the accused. The judges return these cases to the police for a variety of reasons, e.g., small administrative mistakes, absence of sufficient proof that a social media post was made by the accused, absence of the accused while the protocol was being drawn up or mistakes made while registering the violation.

In some cases, judges state their position towards the case more clearly. For example, the ruling in May (case № 5-1324/2022) by the Vyborg District Court of St. Petersburg stated that «the green ribbon tied to the monument and the «Peace to the World'' sticker placed on the monument undoubtedly do not imply […] an act directed at discrediting the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation and at diminishing their authority, i.e., at destroying the public confidence in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation or undermining their authority, and do not prove beyond reasonable doubt that an act of violation had been committed.»

In another May ruling (case № 5-646/2022), the October District Court of Arkhangelsk reminded the police that there is no ban on discussing the «special military operation» in Russia: «The first disposition of Part 1 of Article 20.3.3 does not entail that any discussion of the special military operation is forbidden on the DNR, LNR territories and in Ukraine.»

In a March ruling (case № 5-34/2022), the Uvelsky District Court (the Chelyabinsk region) required the police to provide a linguistics opinion letter that the slogan «No to War» discredits the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation:

«The materials presented in the case do not include an opinion letter by a linguist stating that the slogan „No to War“ discredits the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation to defend the interests of its people and to uphold international peace and security or contains public appeals to prevent the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation from being used for these purposes.»

In a June ruling (case № 5-172/2022), the Khasan District Court of Primorie did not see the slogan «Glory to Ukraine» as punishable: this slogan does not contain any evidence of discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation to defend the interests of its people and to uphold international peace and security».

The court hearing of the case of Vadim Dudarev, a St. Petersburg protester, also ended in his favour.

«I noticed that the report said that I was being accused of 'discretization', not 'discreditation'. The former is a scientific term meaning «discernment». Either there was a plan to acquit me or 'discretization' helped, ” says the man.

Alexei Podgornykh from St. Petersburg also protested against the war by picketing. He was detained holding a poster with a quote from George Orwell, «War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength, no more misrepresentations.»

«The police officers who detained me consulted with their superiors about every move. What to do? Where to take me? Under what article to charge me? At the police station they didn’t know what to write in their explanatory reports either, ” Mr. Podgornykh recalls. «I show up in court at 10 a.m., but nobody is expecting me. It turns out that the police haven’t handed over the file yet. The file arrived around 11 a.m. — 12 p.m., but the judges were already busy. I was told that one of the judges would be free soon and would see me. As a result, the hearing took place at about 1 p.m.»

Mr. Podgornykh said that he considered it meaningless to voice his opinion in court because «there are no humans and no laws there». In his speech, the man referred to the articles of the Constitution on freedom of speech and freedom of assembly and noted that there was nothing written about the armed forces of the Russian Federation on the poster.

The judge acquitted him but advised not to protest again. The man’s friend, with whom he was detained, stayed in court from 10 a.m. until 7 p.m. Another judge found her guilty of discrediting the army.

Another interviewee of OVD-Info, who requested anonymity, was detained in Krasnodar near a protest rally in early March. The police drew up a report under Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code for allegedly chanting anti-war slogans.

The interviewee says she was filming a large group of police officers near the rally on her phone, so her own detention was caught on video. The district court did not watch the video. In the regional court, she was represented by an OVD-Info lawyer. The judge watched the video made by the detainee, as well as the footage from the Smart City system. The case was sent back to the district court, where the woman was acquitted. The judge said she «won’t argue with the regional court.»

After that, the woman was again summoned to the police station where a report was drawn up under Article 20.2 of the Administrative Code (violation of the established order for holding rallies). But this case also fell apart in court.

In late July, the Ministry of Justice circulated guidelines to the regional authorities on how to conduct an examination under 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code and 207.3 of the Criminal Code. As instructed by the Ministry of Justice, «discrediting» is to be understood as «deliberate actions aimed at undermining confidence in government bodies and diminishing their authority». The material should include a discussion of the use of the armed forces of the Russian Federation and provide grounds for their negative evaluation. According to the Ministry of Justice, the slogan «No to War» does not constitute discreditation.

On July 23, 2022, the telegram channel «VCK-OGPU», which covers the work of law-enforcement services published an internal analysis of the practice of applying Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code conducted by the Ministry of the Interior. The document, signed by Deputy Minister Alexander Gorovoy, discusses problems with applying Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code. Mr. Gorovoy notes that often police officers do not enclose photo/video evidence and witness statements, enclose results of poor-quality evaluations, and initiate administrative cases under Article 20.3.3 for statements made before this Article was added to the Administrative Code.

Among the reasons why cases under Article 20.3.3 fall apart the Deputy Minister named initiating both an administrative and a criminal case for the same violation, lack of information on whether the person has been officially notified about administrative charges against them, in case of private messages — no evidence that the violation was committed publicly.

Mr. Gorovoy suggested organizing special training sessions for police officers on how to correctly identify offenses under Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code. Another proposal by the Deputy Minister was to improve communication between police experts and field officers of the Ministry of the Interior.

Bypassing the ‘vertical’

As explained by lawyer Svetlana Sidorkina, who defends those detained under Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code in courts, a ruling issued by one judge does not need to be taken into account by other judges because the Russian legal system is not precedence-based. «When it comes to judicial practice, rulings in our country are made according to the beliefs and convictions of the particular judge. Most likely, there simply are judges who believe that people should not be prosecuted [on these grounds], ” says the lawyer.

Mikhail Biryukov, a lawyer who also works on cases launched for anti-war statements, believes that the chances of getting a ruling in favour of an accused in regional courts are higher than in big cities: «Most of these cases are tried in the regions, where the 'vertical' of judicial power is not as rigid.»

Mikhail Pashin, a retired federal judge and professor at the Higher School of Economics, also observes that the judges in small towns have more room for maneuver than their colleagues in cities with a million-plus population. According to him, large courts hold weekly meetings to figure out how to apply the new laws — in a megapolis such meetings are easier to organize than in the regions.

«In the minds of judges, there is a notion that constitutional norms of freedom of speech must not be violated. I believe this is why some judges do not consider as crimes or misdemeanors harmless slogans that one could hear both in the Soviet times and nowadays. Yet judges are also guided by judicial practice, which, in turn, is set by administrative regulations as interpreted by higher judicial officers, ” explains Mr. Pashin.

In addition to clarifications at internal meetings, written instructions may also be circulated. And most judges comply with these instructions.

«I would say, these judges rely on external beliefs rather than on their own. However, I suppose many believe that this is the way it should be, and that freedom of speech, unlike loyalty to their superiors, is not a value. There is judicial practice, which serves as the primary reference for the judge. One shouldn’t think that in every case a superior calls the judge with instructions to make a particular decision, ” says Mr. Pashin.

According to him, if the judge’s decision is reversed by a higher court, this may have a negative impact on his or her career: the reversal would remain on their personal record and may lead to their declassification to a lower category, which would affect their salary. In the worst case, it may come down to resignation.

The former judge points out that if one wants to remain a judge, one is forced to comply: «As with journalists: either you follow the editorial policy or you quit. A judge cannot assert their own idea of the law if the judicial system works differently.»