This is the story of the first organisation in the USSR that fought for the rights of queer people. It was founded by Ukrainian polyglot Oleksandr Zaremba. He called himself a «Soviet patriot» and opposed the homophobic rhetoric of American reactionaries.

Translated by OVD-Info volunteers

Localized by OVD-Info Fellow Paulina Bogusz.

Learn more about making a difference with our fellowships here.

In January 2024, Pyotr Voskresensky-Stekanov, an LGBT activist from St Petersburg, was surprised to read the text of the Russian Supreme Court’s decision to declare «the international LGBT social movement» extremist. According to the court, the movement came to Russia having originated «in the United States in the 1960s as part of its birth control policy.»

The year 1984, which is listed as the year when the «international movement» began its activities in Russia, was the first to cause surprise. Russian LGBTQ%2B activists believed that the court took the date from a Wikipedia article.

This article was written by Voskresensky-Stekanov himself in 2010. In it, there is a small section devoted to the Leningrad project called «Blue Laboratory.» This was the first Soviet organisation created to protect the rights of gay people.

Pyotr learned about its existence in 2009 from the book «Sexual Culture in Russia. Strawberry on a Birch» by Soviet and Russian sexologist (as well as anthropologist, sociologist and philosopher) Igor Kon. «Then, I noticed his disparaging assessment of the fact that such a circle had been created. I decided that this was unfair, and started looking for information,» Voskresensky-Stekanov told OVD-Info.

In the chapter «Blue and Pink» Igor Kon wrote: «Until the late 1980s, Soviet 'blues' [goluboy] were victims; they could only complain about their fate and beg for leniency. However, it’s true that there were certain exceptions. In 1984, about 30 young people in Leningrad, led by Oleksandr Zaremba, united into a community of „gays and lesbians“.

«Unlike Kon, I believe that the creation of a classic LGBT rights-oriented dissident circle right before perestroika had a meaningful impact on the history of the LGBT movement in Russia,» remarked Pyotr Voskresensky-Stekanov. «It was in the Laboratory that the very idea of human rights activism emerged, many activists gained their first experience, and connections with the West were developed.»

In his article for Wikipedia, he initially cited 1984 — the same year as Igor Kon — for the creation of the «Gay Laboratory». But in 2017, after reading an article by Sergei Shcherbakov, one of the group’s members, Pyotr changed the date to the correct one: 1983.

Voskresensky-Stekanov says the Supreme Court could have borrowed the year of the emergence of the «international LGBT movement» in Russia from old documents from the Centre for Combatting Extremism, which actually took the year from the unedited article on Wikipedia around 2011. Also, he believes the court could have been provided the year 1984 directly from the «KGB case on the dispersal of the 'Gay Laboratory’».

«Or it’s a joke — an Orwell reference,» the activist added.

But the prosecution of Russians for organising an «international public LGBT movement» (part 1 of Article 282.2 of the Criminal Code) has already begun in earnest: in March, the Central District Court of Orenburg sent the art director, administrator and owner of the club Pose to pre-trial detention for this very reason.

A Dutch visitor, a gay Soviet and the «Pravda» newspaper

In August 1983, an unnamed Dutchman, member of the international LGBTQ%2B association ILGA, came to Leningrad. Here, he visited a «Soviet gay man» with whom he had been in contact since March and who had just moved to Leningrad from Kyiv, where he had completed his graduate studies in social psychology.

In the report for the ILGA newsletter, the Dutch visitor did not specify the surname of his contact, only his first name — Sasha — and his age — 27 years old (that’s how old Ukrainian Oleksandr «Sasha» Zaremba was at the time — OVD-Info).

According to the report, Sasha worked as a teacher of English and French, while knowing many more languages (eight to ten, according to one of the participants of the «Gay Laboratory»), including Dutch. He read the Dutch Communist Party newspaper De Waarheid (Pravda), which «could be bought in major Soviet cities». The paper had been publishing news about the queer movement in the world for some time.

Sasha complained to the Dutchman that male and female same-sex relations were taboo in the USSR. There was a media campaign against gay people, and the authors of the few non-fiction books that mentioned same-sex orientation condemned them usinganti-scientific arguments of «American reactionary conservative and even Christian propagandists».Sasha cited Antonina Khripkova and Dmitri Kolesov’s 1982 teacher’s manual called «The Boy, the Adolescent, the Young Man, ” that called same-sex orientation a „defect of upbringing“.

Zaremba borrowed another example from an unnamed Soviet work, whose authors described the struggle for gay equality in Western European countries as follows: «In capitalist countries they are not ready to recognize the equality of men and women, but equality is guaranteed to such a perversion as homosexuality».

Sasha shared his plan with the Dutchman to create a «gay group» in Leningrad andfight for the legalisation of same-sex relationships in the Soviet Union. He asked that the group be supplied with scientific literature and news, either by mail via Hungary and Czechoslovakia, where correspondence was not as strictly censored, or by visitors to the USSR with official invitations — privileged people from other countries were less scrutinised.

In December of the same year, 1983, the Canadian newspaper «The Body Politic» reported that the first «underground gay organisation» in the USSR had been established. In October the groupheld educational sessions «on different aspects of gay identity and the gay liberation movement». A seminar «for gays and lesbians from Moscow, Tallinn, Riga and Kyiv» was planned for November.

Part of an article in The Body Politic newspaper of December 1983; the text was placed next to an advert for a hotel in Key West, Florida / Source: Pink Triangle Press, Internet Archive

The article quoted the same Sasha, «a group spokesperson and Communist Party member.» He stated that «The biggest problem for our gay movement is that people do not believe that change is possible.»

Criminalized «sodomy, ” and gay communists

On 16 June 1983, Yuri Andropov became General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Leningrad gay community was wary of the change in power, not knowing what to expect. The Dutch visitor wrote in his report that in 1983, unlike the previous summer, there were «no drag queens and brightly painted faces» at the «pleshka» (the traditional meeting place for gay people in 1983) in the Yekaterininsky garden in the centre of Leningrad. However, the Dutchman continued, no other changes were visible and at the intersection of Nevsky and Mayakovsky Streets there was still «a gay bar known among Leningraders as ‘Mayak’ (lit. Lighthouse), where gay people queued to buy beer for 45 kopecks.»

At the same time, however, the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic containedarticle 121 on «sodomy». It was introduced in 1934 and at that time it provided for three to five years in prison for «voluntary» gay relations and five to eight years for «violent» ones. In 1960, after a reform of the code’s sectionon voluntary relations, the lower limit of punishment disappeared from the article. Researchers give different figures for the all-time total number of people convicted under this article, with the average estimate being 60,000. Among famous people who received this sentence were singer Vadim Kozin and Armenian film director Sergei Paradjanov.

However, women were not prosecuted under this article. Sasha (under this name Oleksandr Zaremba appeared in ILGA reports) told the Dutch visitor that lesbian relationswas not criminalised «because of the male chauvinist idea that women have no sexual identity.» Soviet lesbians, he argued, had an easier life — «and are more radical in their advocacy for gay rights than men».

There were only four women in the aroundthirty participants of the «Gay Laboratory.» One of them was Irina, Oleksandr Zaremba’s wife. Another member of the «Leningrad Group, ” Sergei Shcherbakov, wrote about this in his article „How it began under totalitarianism, ” specifying that weddings between gay people and lesbians were common in the USSR.

Yet, the couple may have had a different reason to marry. Lizet Hansen, a Dutch woman who studied in Russia in the first half of the 1980s was a witness at Zaremba’s wedding and told OVD-Info: ‘There was a serious problem with housing. A single person had few rights to living space in Leningrad. Irina was threatened with eviction, so she and Oleksandr decided to get married.» According to Lizet’s recollections, Zaremba invited non-Soviet citizens to the wedding, which greatly confused the registry office staff.

At the time of publication of Sergei Shcherbakov’s article in RISK magazine in 1991, Irina, according to the author, lived in Finland.

«Oleksandr Zaremba decided to organise a group for gay people along the lines of Western organisations, ” Shcherbakov recounted. „The group’s task was to build self-awareness for gay people, learn foreign languages in order to read queer literature, fight for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, and organise gay clubs similar to Western ones.“

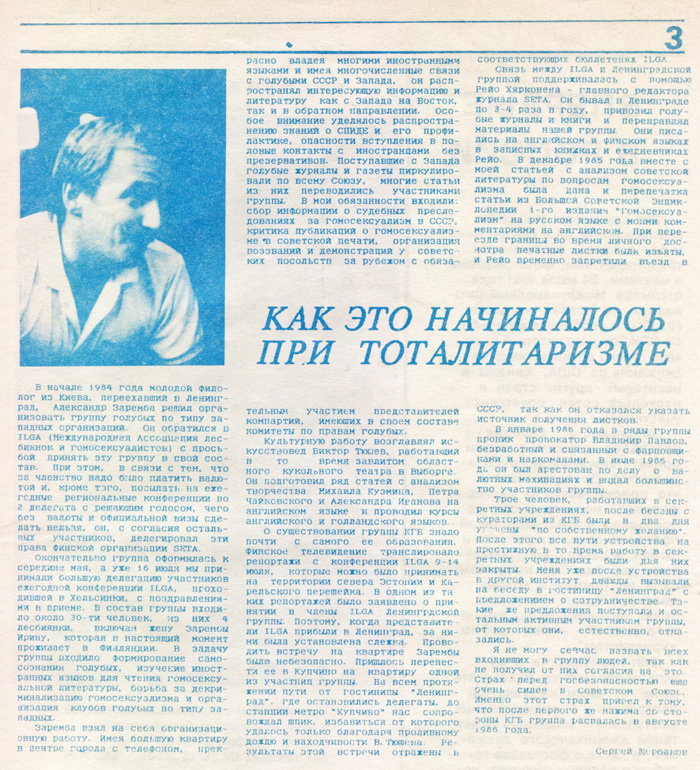

Article by Sergei Scherbakov in the first issue of RISK magazine, 1991

According to Sergei Scherbakov, Zaremba immediately asked the international organization ILGA to accept hisgroup from Leningrad as its member. The association’s archives still have a transcript of an audio cassette that Sasha recorded in English in Leningrad in December 1983. The young polyglot lamented that Soviet people liked the Western way of life better than communism: ‘They just pick up American and Western European patterns and adapt them to our conditions.» Zaremba recalled that in the 1920s, the Soviet Union had the world’s most progressive legislation on sexual rights and freedoms — but now the country «blindly imitates ” the most reactionary practices of the United States, South Africa, and Israel.

«As a Soviet patriot, I will never tolerate the cynical and demagogic propaganda against millions of gays and lesbians, citizens of the USSR, ” Sasha added.

Since ILGA membership fees were in a foreign currency (which Soviet citizens could not transfer abroad, even if they had it), and membership involved the presence of two delegates at an annual conference (which the «Gay Laboratory» could not afford either), the Leningrad organisation was represented in the international association by the Finnish SETA.

A visit from the Finns, Katkin Garden, and Zaremba’s communal appartment

«An Aeroflot flight from Helsinki has just landed at snow-covered Pulkovo Airport in Leningrad. Stringent customs officers in grey uniforms are waiting for the arriving passengers from the plane. ‘Do you have any roubles, printed materials, gifts? Come this way! ’ A personal search reveals no forbidden literature, drugs or pornography. ‘Welcome to the Soviet Union! ’ A few hours later we are already sitting in a flat in the centre of Leningrad.»

Thus began an article titled «The Organisation of Homosexuals in the Soviet Union, ” published in the first issue of the SETA magazine in 1984. Its authors later indicated that they were in fact carrying literature on same-sex relations, but that it had not been confiscated because „only nude photographs were prohibited.“

One of the authors of the article was the magazine’s editor-in-chief, the Finnish journalist Reijo Härkönen. Later, it was he who maintained links between ILGA and the «Leningrad Group, ” as Shcherbakov called it. Reijo travelled to Leningrad three or four times a year and smuggled literature both ways — from the USSR to Finland and back. Members of the „Gay Laboratory“ wrote notes in English and Finnish in Härkönen’s diaries to make them harder to detect during inspections.

Another Finnish activist, Olli Stolström, who had been involved with SETA since its founding in 1974, sometimes travelled to Leningrad with Härkönen,. «We took scientific texts with us — mainly on decriminalisation [of same-sex relations] and the declassification of mental health, ” he recalls in a letter toan OVD-Info correspondent. „At the time, many of us were left-wing activists of sorts, associated with the Social Democratic Party of Finland.“

Olli, born in 1944, describes his generation as «very international»: «I was involved in the financial support of ILGA in 1978. I worked closely with Kurt Krikler from HOSI Wien (an Austrian LGBT organisation — OVD-Info), who was the initiator of ILGA. Thus, the ‘international LGBT movement’ is not entirely fictitious.”

«Every foreigner, even crooked, old or bald, was welcome. That’s why, when Shurik Zaremba brought Finns to Katkin Garden, we surrounded them with care and attention, ” wrote Olga Krause about the winter visit in her book „Katkin Garden.“ Olga is listed as one of the participants of the „Gay Laboratory“ in the aforementioned Wikipedia article.

Catherine (aka Katkin) garden in the 1980s / Photo: Lothar Willmann

According to Krauze’s account, «Shurik’s human rights initiative did not go down well with the Katkin Garden’s regular visitors. One of them, nicknamed ‘the Spaniard’, is said to have said: ‘You, Zaremba, will go to prison… And one of these young fools will report you, they definitely will.’»

«And so these Finns left our garden with Zaremba and a bunch of youngsters, ” Krause wrote.

One of the eyewitnesses of those years, in an unpublished interview seen by OVD-Info, said that «the participants in the ‘Laboratory’ were ordinary gays and lesbians, friends and acquaintances, perhaps more passionate and inclined to social activity than the rest.»

One of them, Sergei Shcherbakov, was responsible for gathering information about the persecution of gay people in the USSR, as well as for critiquing Soviet publications and organising demonstrations outside of Soviet embassies abroad. Cultural work was led by an art historian who lived in Vyborg, near the Finnish border.

The participants of the «Gay Laboratory» met at Zaremba’s in a communal flat (a kommunalka) near the Tavrichesky Garden. The flat had the advantage of having a telephone. Ivan (name changed), who visited the flat once in 1984, described it to an OVD-Info correspondent: «We noticed that [Zaremba] lived modestly. He had a piano that didn’t play. There was no lock in the apartment: whoever wanted to come could come, day and night. [Zaremba] was shabbily dressed.»

Pouring rain, a meeting in Kupchino and the lack of a samovar

«I heard that in Kupchino they held a constituent meeting in someone’s flat and recorded an interview about our life, ” Olga Krauze said about the appearance of the „Gay Laboratory“ in her book.

Sergei Shcherbakov was sure that the KGB knew about the existence of the Leningrad Group from the very beginning, because they had seen a report on Finnish television (the signal was picked up in northern Estonia and the Karelian Isthmus) about the admission of the «Gay Laboratory» into ILGA. So when an international delegation arrived in Leningrad in the summer of 1984, it was placed under surveillance.

The ILGA delegation was composed oftwelve people from five different countries. One of the participants, Ernst Strohmeyer, a contributor to the German-language magazine Lambda Nachrichten published by HOSI Wien, described the visit in an article. He wrote that the arrival of the delegation was «well prepared for, ” and over the course of three evenings the delegates met with the „Gay Laboratory“ participants „in various private homes.“

Sergei Shcherbakov later wrote that it was not safe to hold the meeting at Zaremba’s flat because of surveillance, so it was moved to the flat of one of the group’s members in Kupchino: «All the way from the 'Leningrad' Hotel where the delegates were staying, to the Kupchino metro station, we were followed.We managed to get rid them of only thanks to the pouring rain.»

Strohmeyer described the meeting as follows: «We were unlucky with the weather: we arrived at our destination soaking wet because of the heavy rain. It was a terminal metro station in a newly built neighbourhood similar to those on the outskirts of all European cities — faceless residential blocks clustered together. Each [delegate] could choose which section to participate in: the theory group (gay workshop) [which was located] in the living room, the cultural group in the bedroom, or the lesbian group in the kitchen. We tried to dry our clothes with a hairdryer and warmed ourselves with tea. No, not from asamovar — it was too expensive and, as we learnt, people just couldn’t afford it.»

The delegate found out that the «Gay Laboratory» existed off ofpersonal contributions of itsparticipants. The organisation was headed by a committee of five people who met every week. This committee decided on the membership of newcomers.

«Contacts with possible members, and gay people in general, takes place mainly in cinemas, theatres, bookshops or on the street, ” Strohmeyer recounted. „Candidates are monitored for two to three months: they are contacted regularly, to try to learn something about their lifestyle, work, and family.“

The activists informed the delegates that they «could reach up to a thousand people in Leningrad» and also establish correspondence with about two hundred «like-minded people in all major cities of the USSR.»

The delegation’s last meeting with members of the «Gay Laboratory» took place in a beer hall (which Strohmeyer called a ‘pub’ in his report) among «workers, probably» and «a group of sailors»: «Upon handing in a token at the entrance, each attendee received a portion of fish — dry, very salty, and as hard as a cracker — and half a litre of beer, not at all as sharp and strong as [Austrian] beer. But after tasting the fish, there was nothing left to do but drink this beer.»

Being a «notable group of tourists, ” the delegates failed to appreciate the „pick-up opportunities“ at the drinking establishment.

At the end of the trip, Ernst Strohmeyer concluded that gay people in Leningrad faced roughly the same prejudices and difficulties as in the West. Meanwhile, in the same year, 1984, in Strohmeyer’s homeland of Austria, the first ever gay pride parade took place.

The delegation brought back an English-language message compiled by Oleksandr Zaremba from the trip. He wrote that the organisation had decided to create a «Gay University of Leningrad» with courses in foreign languages, the history of same-sex relations, and «Marxist theory and problems of the gay liberation movement.»

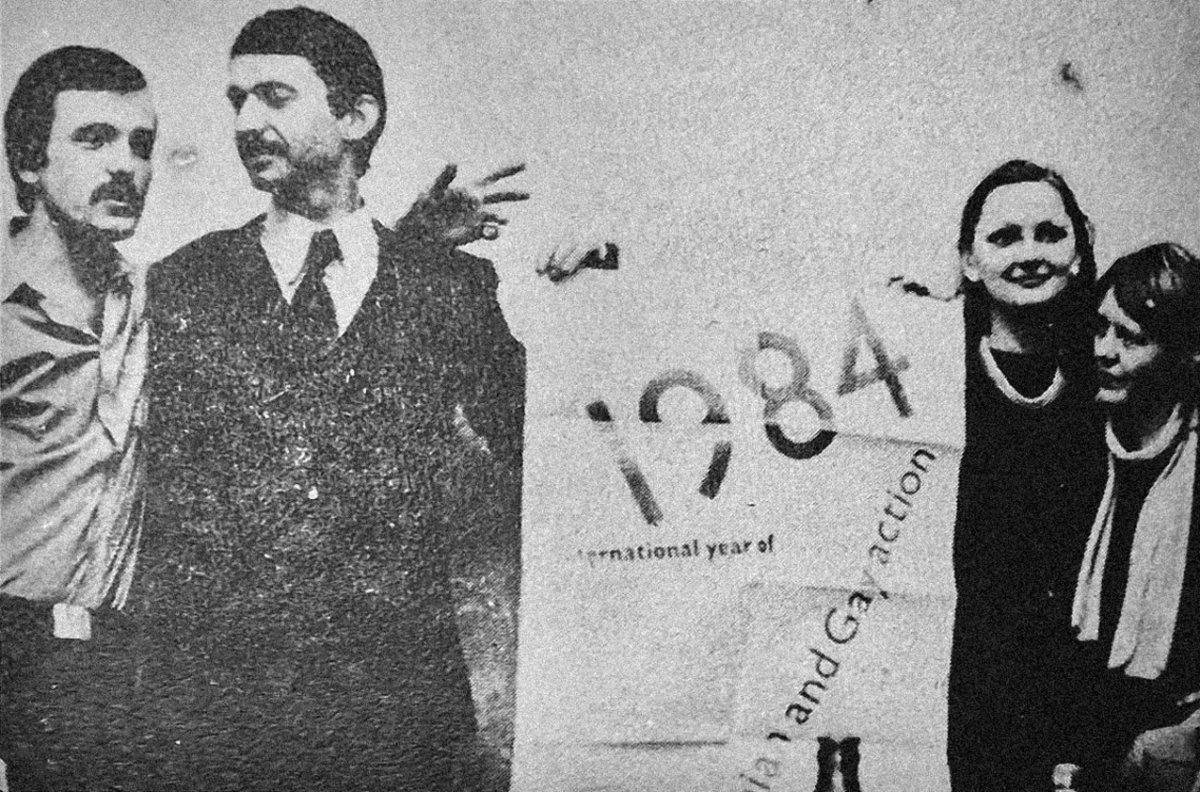

(From left) Sergei Shcherbakov, Oleksandr Zaremba, Irina and Lizet Hansen with a 1984 ILGA poster at Oleksandr and Irina’s wedding / Photo provided by Lizet Hansen

The author presented the members of the «Gay Laboratory» as «‘Marxists and patriots of Russia.» He called the rest of the Soviet gay community the vast majority of them — «pathological hunters for new sexual contacts, not interested in anything else.»

Ivan, who first met Oleksandr Zaremba in 1984, is still convinced that he was a KGB agent: «Everyone was talking about it. It was heard on the grapevine. Allegedly someone was in the KGB [building] and saw photos of Zaremba there.»

KGB agents and an atmosphere of paranoia

In the 1980s, KGB agents considered gay people easy prey for Western intelligence, Sergei Shcherbakov told a conference in Tallinn in 1990. The stereotype was explained by the fact that many Soviet gay people dreamed of moving to the West. Therefore, the agents acted proactively.

«Those whom the KGB chose as informants were first brainwashed. They were offered jobs with fixed hours so that they could combine them with visiting people from foreign countries. They were given new apartments, bypassing the waiting list. ‘The client, ’ in turn, had to organise meetings in this apartment — both with Westerners and influential Soviet gay people. Such apartments were always bugged, and there was usually a disguised KGB agent present at the meetings, ” Shcherbakov said.

According to him, methods like these were not particularly successful. Some gay people were fired from their jobs, but otherwise Soviet gay people communicated with people from foreign countries without interference. «Some of the [KGB] informants, despairing of the isolation and mistrust of the gay community, took their own lives» (OVD-Info wasn’t able to confirm this information through other sources).

In his letter to an OVD-Info correspondent, Finnish activist Olli Stolstrem recalls that at the same Tallinn conference in 1990, «a contact person from KGB named Dyachenko» was present: «He interviewed me for several hours, and I gave him dozens of scientific articles.»

«Back then it all felt quite cordial: it was the time of perestroika and glasnost. The future looked promising. But then Putin seized power» Olli writes.

«Back then there was a process of leaving totalitarianism, and now there is a process of entering it, ” says Pyotr Voskresensky-Stekanov, an author of the Wikipedia article about the LGBT movement. He compares the atmosphere (of paranoia, suspicion, fear) in which gay people of Leningrad lived in the first half of the 1980s to the atmosphere of today. Pyotr emigrated from Russia after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

«Of course, there is paranoia when actual KGB-FSB „agents“ are active. There is immense fear» he continues. «The difference is that back then that fear was of an ‘innate’ nature, and the community was fragmented. Right now that fear is ‘taught’ to a quite organised community. This process will be much harder for the government, though still not impossible.»

During meetings with people from foreign countries, Oleksandr Zaremba also spoke of the atmosphere of paranoia in gay communities of the USSR. He claimed it was the reason why not many gay people dared to build actual relationships, limiting themselves to «one night stands and encounters in secret.»

On an audiotape for ILGA, Zaremba stated: «I am not a KGB agent.»

Gorbachev as Superman and murder in a St Petersburg apartment

The Finnish liaison for the «Gay Laboratory» Reijo Härkönen noted in his letters in 1985 that the situation in Leningrad was confusing; there was still no completely functioning group, and mutual conflicts and accusations of collaboration with the KGB occured every day.

From the 11th to the 13th of October, Härkönen once again visited Leningrad, where he met with local activists and provided them with materials about AIDS, and as well handed over several letters from the West. The Leningrad residents were quite astonished by the fact that Reijo, among other foreign activists, was the only foreign activistwho still maintained constant contact with them.

Presumably, this was because in 1982 the first cases of AIDS were registered in EuropePanic began. In the first half of the 1980s foreign LGBT publications and activists focused on HIV/AIDS-related topics and the struggles of local communities. Soviet gay marxists were no longer a relevant topic. In the USSR, the first HIV screening was only done in 1987, and it was in that same year that the first case of the disease was officially confirmed (the real first cases — undetected ones — may have occurred back in 1970s).

The KGB was aware of Härkönen’s meeting with activists and he was put under surveillance. On his way back [to Finland], Reijo, as usual, brought along materials from Leningrad, including a rewrite of an article called «Homosexuality» from the first edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, with comments in English by Sergei Shcherbakov. He was searched at the border. «Reijo was temporarily (for 5 years — OVD-Info) banned from entering the USSR, because he refused to indicate where he received the leaflets, ” said Sergei Shcherbakov in his article on the „Gay Laboratory.“

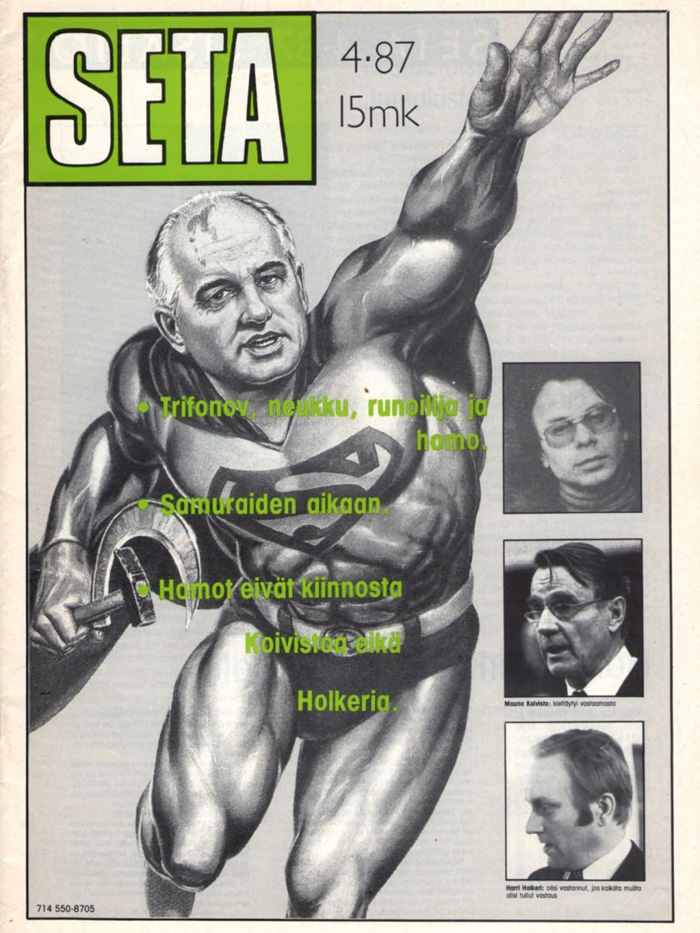

Other sources claim that Reijo’s work visa was cancelled two years later, and the ban followed the SETA magazine’s special edition in 1987. The cover showed General Secretary Mikhail Gorbatchev as Superman in the homoerotic style of the artist Tom of Finland.

Cover of the 4th edition of the SETA magazine, 1987, with Mikhail Gorbatchev / Photo: Työväen Arkisto

A couple of months after the incident at the border, Vladimir Pavlov, an «unemployed personassociated with the black marketeers», infiltrated the «Gay Laboratory.» Sergey Shcherbakov was confident that Pavlov was a provocateur. In July, Pavlov was detained for currency fraud, and he gave the KGB the names of most of the group’s members.

After a conversation with KGB agents, three of them «were fired within two days» from their jobs in secret institutions. Agents called Shcherbakov in for a conversation twice (to the same Leningrad Hotel where the ILGA delegation had stayed two years earlier) with unsuccessful attempts to recruit him.

The «Gay Laboratory» ceased to exist in August 1986. «It was only in 1990 that ILGA received the next application for membership [from an LGBT organisation] from the USSR» stated Nigel Warner, the ILGA-Europe representative.

In 1991, the first LGBT organisation called the «Wings» Association of Gays and Lesbians» was officially registered in Russia. This organisation was also based in Leningrad. Its activists rooted for the cancellation of Article 121 (on sodomy). This happened in 1993, the same year when the current Russian constitution was adopted. On May 27th homosexuality wasexcluded from the Russian Penal Code. As the founder of «Wings» Aleksander Kucharsky later recalled, gay people from St Petersburg rented a ship to celebrate the occasion. «It sailed the Neva all night long with roaring music.»

In Ukraine, same-sex relationships were decriminalised in 1991. Ukraine was the first post-Soviet state to enact this change.

Sergey Scherbakov was murdered in the first half of the 1990s, states his acquaintance Ivan (and affirms Pyotr Voskresensky-Stekanov). According to Ivan, it was an ordinary homicide; Scherbakov was stabbed and robbed. «He lay in hisapartment for several days. His neighbours called the police because of the smell — when they opened the apartment, there he was. Dead.»

The art historian from Vyborg, responsible for all cultural work of the «Gay Laboratory» died in 2017. In obituaries, his colleagues, friends and apprentices called him a well-dressed man with perfect manners, a true lover of books, with an ambiguous personality.

Reijo Härkönen was not only an activist and journalist, but also a traveller. In 2009, he published a book on his travelsto Nepal which began in 1982. Reijo died in 2021, at the age of 72. A Finnish newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat, mentioned in an obituary an episode where he was denied entry to the USSR but did not specify the reason for the ban.

It is not clear what happened to Oleksandr Zaremba right after the closure of the «Gay Laboratory.» Some sources state, with no further details, that he was imprisoned. «As soon as [Zaremba] served his time, he returned to Kyiv and never ever came to St Petersburg again» wrote Olga Krauze in her book «Katkin Garden.»

Olga herself lives in Kharkiv, which is under daily attack from the Russian army. She did not respond to the request sent by OVD-Info.

In an unpublished interview, one of the «Gay Laboratory» members said that he had fruitlessly tried to find Zaremba in 1990. He had been further informed that «Zaremba does not want to participate in public LGBT lifeL» «He came from nowhere and disappeared into nowhere.»

In her book published in 2017, Olga Krauze stated that Oleksandr Zaremba died in Kyiv «alone and angry at the whole world.»

Department of Jewish history and the Gay Movement in Ukraine

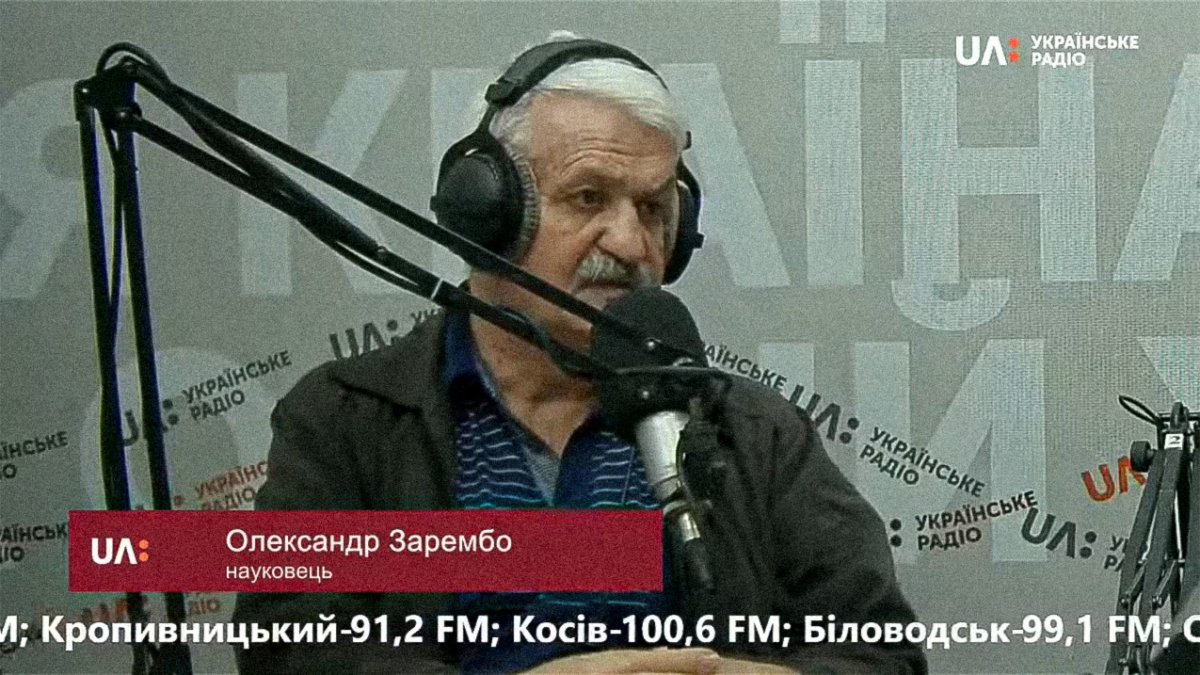

On 21 August 2020, the «Ukrainian radio» published a talk on the «Preservation of cultural identity of national minorities during reforms of municipal government.»

One of the discussion’s participants, a grey-haired man with a moustache wearing a striped polo-shirt and dark green bomber jacket, spoke in defence of the Hungarian-speaking Roma culture. Hungarian-speaking Roma are representatives of an ethnic Roma subgroup that live in Zakarpattia, among other places.

«Why does nobody speak about these people’s differences? They also have some needs. We don’t say that Russian-speaking Ukrainians are not Ukrainians, do we? We consider them Ukrainians, even if they speak Russian. Consequently, Hungarian-speaking Roma also have a right to be spoken about, ” (translation from Ukrainian — OVD-Info) claimed the expert. The expert’sname was Oleksandr Zaremba and he worked for the Kuras Institute of Political and Ethnonational Studies in Kyiv.

Oleksandr Zaremba on air on the «Ukrainian Radio, ” August 2020 / Screenshot: YouTube Channel „Українське радіо“

OVD-Info was unable to get any information on Zaremba’s activities in the 7 years following the closure of the «Gay Laboratory.» But from 1993, he was the chair of the department of Jewish history and culture in the Institute, established just after the fall of the USSR’s. In 1996, he defended his thesis on the subject of «The linguistic problem in the Jewish national movement.» He wrote a number of scientific works, among them «The Problem of Ingermanland and Scientific Culture of Finland (1989-1992).» It was published in 2001 in the «Ethic History of the European Nations» journal.

In 2010, Zaremba published a book called «The Birobidzhan Project: Identities in the Ethnopolitical Context of the XX–XXI centuries.» The newspaper «Birobidzhan star» wrote that «the Ukrainian scientist Oleksandr Zaremba had presented a truly invaluable gift to Birobidzhan.»

The institute where Zaremba used to work informed us that he left the institution in 2020, and he has had no ties with the establishment ever since.

In post-Soviet times, Oleksandr Zaremba hardly participated in LGBT-oriented events. We were only able to find two such events, both taking place in Ukraine. The first was a 2008 round table talk called «New Homophobic Tendencies in Eastern Europe.» The «Ukraine Gay Portal» described the event as follows: «Oleksandr Zaremba began the discussion […]. He mentioned […] the Finnish President [Tarja Halonen] who had been a leader of a national LGBT-organisation (the aforementioned SETA – OVD-Info). He remarked that the gay movement in Ukraine is the most developed in the whole post-Soviet space.»

The second event was a conference called «Same-sex Partnership in Ukraine: Today and Tomorrow» that took place in Kyiv in 2017. Zaremba was announced as a participant in one of the panel discussions.

A participant of both events told anOVD-Info journalist that several years prior, Ukrainian activists had lost touch with Oleksandr and that they «do not know whether he is alive.»

Galya Sova

The author thanks Pauliine Lukinmaa, a research associate at the University of Eastern Finland and LGBT-activist Pyotr Voskresensky-Stekanov for their help with the preparation of this material.