Sergey and Anastasia Gordienko live in the Odessa district of Siberian Omsk region, in an abandoned village that’s not even marked on maps. They’re surrounded by ethnically Ukrainian villages. The Gordienko family became outcasts — not just because they live far from everyone, but also due to their anti-war beliefs and the criminal cases filed against them. We also tried to understand why ethnic Ukrainians from the surrounding villages volunteer to fight for the Kremlin.

Chapter One: in which the blizzard begins

Odesskoe village, a roadside cafe. Grumpy. men enter, shaking themselves off, snorting and talking anxiously. They are from Kazakhstan. They crossed the border, 18 kilometres from here, and now the road is closed: a blizzard is about to start. Outside, the wind gathers strength, its icy fingers sweeping through the landscape, and the soft, mournful howl of the impending storm drags swirls of snow along the deserted road.

The village was once called New Odessa — this is how Ukrainian settlers of the early 20th century named it in memory of theirhomeland; later, the first part of the name faded away.

In the early 20th century, during the reforms encouraging industrious peasants to acquire their own land, peasants from Ukraine — then mostly a part of the Russian Empire — settled Russia’s Siberian frontier. The majority of the residents here are ethnically and culturally Ukrainian to this day. They named the surrounding villages after Ukrainian locales — Gannovka, Blagodarivka, Zhelannye, and Bunyakovka. Some of these still exist in Ukraine.

«Welcome to Khokhland! That’s what we call it here!» — Evgeniy appears at the cafe door, wrapping himself tightly; he picked us up from the bus station and brought us here in the car. Kind and stocky Zhenya (short for Evgeniy) chuckles good-naturedly. His late mother was friends with Anastasia Gordienko, who we are visiting today. Zhenya and the local Cossack Ataman [Chieftain] Grisha volunteered to help us with that.

«In some villages here, if you speak Russian, they immediately figure that you aren’t from around here», explains Evgeniy. «In Blagodarivka, children couldn’t understand the young Russian-speaking teachers from the city, so retired teachers had to go back to work».

Zhenya’s family tree is all Cossacks and Molokans in his family tree. He is a farmer and keeps a flock of sheep. He lives alone, and his daughter studies in Tomsk, a major Siberian city, while his ex-wife left for Germany. She quit her job at school because of the war, when teachers were mandated to run compulsory propaganda classes aimed at enforcing the official Kremlin narrative about the war.

«So many from Blagodarivka marched off to war, I am amazed», Zhenya is indignant, «almost all Ukrainians [fighting against Ukraimians]! And many went willingly. I asked them: „Have you lost your mind?“ I even told one: „You idiot, where do you think you’re headed?“ And he answered [in Ukrainian]: „I’ll go fight the Nazis“. „You don’t even speak Russian, what Nazis?!“ And he told me: „I watch ‚Russia 24‘ [a state-funded TV channel], they explain everything there“».

We grab a quick lunch, drink hot tea to warm up in advance, and get ready to leave before the snow blankets the road entirely. We need to get to the spot where Ataman Grisha Ostapchenko will meet us with a snowmobile. There is no other way for us to get to Anastasia and Sergei Gordienko: there is no road to the village of Reshetilovka, as well as there is no school, hospital, or shop in the village. There are no houses there except for the Gordienkos’ home. The village virtually no longer exists.

Chapter Two, in which we drive through a snowstorm

The blizzard is getting stronger. The wind is not howling anymore; it is hissing and whistling, icy and prickly, spiralling into a snow tornado. We can only see a couple of metres ahead. Our car is groaning and spinning its wheels, sending sprays of hard ice flying. Wind-blown snowdrifts are growing like white walls on either side of the road.

Cars ahead of us stall now and then, and drivers shovel them out and pull them on ropes. Our hands and face freeze up at once. The men’s faces are flushed with effort, their eyebrows and eyelashes turned white, drops of moisture freeze on their beards. Nonetheless, everyone is in good spirits. As they work, they huff and puff and curse cheerfully — the storm brings people together.

Suddenly, the veil of snow is sliced by a snowmobile. It comes to an abrupt halt before us, sending up waves of snow. This is Grisha — blue eyes are looking at us through the opening of the frosted balaclava.

«I had been waiting for you, I looked around — and you were nowhere to be seen!» — he says in hoarse Ukrainian.

He takes off his heavy-duty mittens and rubs his huge red hands. We barely manage to open the car door. If you don’t hold the door, it can be blown away in a wind like that; Zhenya says it often happens here. We cram ourselves into the plastic tub attached to the snowmobile with a flimsy rope. The snowmobile jolts, then darts off, and we fly, sputtering ice crumbs and jumping on turns. The white plain around us stretches as far as the eye can see. All at once, the snowmobile brakes to a halt.

«Girls! We’re lost, so I’ll go out to look at the road and you wait here for about an hour!» — Grisha shouts in Ukrainian as he looks back, but seeing our horrified faces, he booms with laughter and the snowmobile jolts into movement again. In a few minutes, a house rises up amidst the wasteland.

Chapter three, in which the story begins

«Holy cow, just look at those shoes!» exclaims Anastasia, staring at our low-rise boots as we enter the house, shaking off the snow. Grisha’s snowmobile roars a goodbye and drives off.

Khazar, a gold-coloured dog, runs to meet us. There is meowing coming from the kitchen.

«This one is called Bureaucrat, this [cat] is Monica, she was born without a paw. Sonya, Yasha, Paramon — Sergey names all the cats», Anastasia introduces the pets to us. «Paramon is banished at the moment though; he has peed all over my curtains. It’s a shame, he is such an indoor cat», she laughs.

Anastasia was born in Sinyavka, a village in the Odessky District about 50 kilometres from the village of Reshetilovka. It is hard to be precise because Sinyavka does not officially exist anymore either. When she was 18, after a course in choir conducting and the accordion, she came to Reshetilovka and started working at the local community centre — this is where she met Sergey. This year marks a milestone — their fiftieth anniversary. They were married at the same community centre.

Sergey soon became a livestock technician, and the young couple moved to the village of Gannovka, where they were offered employment and a flat to call their own. In the meantime, Reshetilovka disappeared. As the USSR in its last years delved further into stagnation, the Reshetilovka collective farm collapsed, the school and the farm were closed. The locals sold off their cattle and moved to neighbouring villages. In 1980, the abandoned village was excluded from all official records. Now, the place where Sergey and Anastasia first met and then married lies in brick ruins — they are visible from their window.

From the window, one can also see a monument to the villagers who died in the Great Patriotic War — a grey arch and several black granite slabs — and a solitary public toilet in the middle of the steppe. All of this appeared here last year, the «official ceremony» took place on June 4th.

«Someone from Gannovka asked me, „Will you come [to the ceremony]?“ I said that if I were to attend, it would only be under the Ukrainian banner! Some villager must’ve snitched, and it all turned into a circus», says Anastasia in Russian.

By «circus» she means the police visit on the eve of the opening ceremony, which coincided with Alexei Navalny’s birthday — the politician turned 47, supporters announced rallies, and Anastasia was heading to Omsk to protest.

«The police came and said „You’re plotting a terrorist attack“. I answered, „Are you completely out of your mind? What terrorist attack?“ Anastasia recalls. „I’m actually planning to go to a rally in Omsk! They issued me a warning [so that I did not participate in 'unauthorised actions']“».

«It’s an anniversary year you know… They might even put you in prison» — Sergei chuckles.

Anastasia has already been under travel restrictions for six months. Now she cannot leave the Odessa region without the investigator’s permission, not even to go to Omsk, or to the nearest hospital. «At the police station, I said, „Your restrictions offended me. I’m 70 years old, raised four children, lived a decent life, and suddenly I’m a threat to the state!“» Anastasia says sharply.

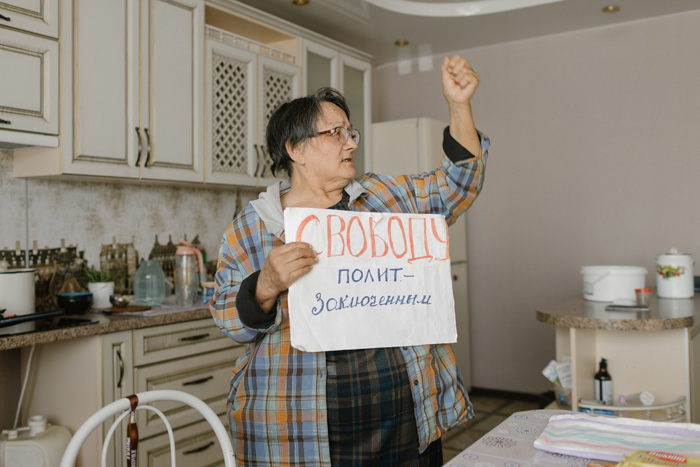

She is suspected of repeatedly discrediting the army (Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) due to her social media posts. She already has a similar administrative charge against her — for an anti-war picket.

Chapter Four, in which «an oppositionist is turned into a revolutionary»

At the monument to Bohdan Khmelnytsky a woman stands in a fall jacket and a green scarf — the video is titled «Police detain an old woman for a poster…» Around her shoulders the woman has a red rope holding a poster with the slogan «Mothers, stop the war!»

Police officers approach the woman, and she screams hysterically: «Rise, o, vast country, rise to mortal combat — against Putin’s dark gang, against the accursed horde!» The next moment they take her by the arms, lift her off the ground, and carry her into a police car amidst the outraged cries of passers-by.

The woman is Anastasia Gordienko, the scene is taking place in Omsk in the early hours of October 26, 2022. At 70 — with a short haircut and only a touch of grey in her hair — she resembles anyone but a quiet old woman.

«I was about to go out [to picket], but my relatives started lamenting: „Oh, they’ll arrest you!“» she says.

Anastasia was unyielding. She feared for her sons (draft had already been announced) and she was ready to fight to the death for them. Both had served their conscription, and her grandson had just turned 21. «I was so depressed when they were in the army, I wasn’t happy about anything, I would milk the cow and cry», Anastasia says. «And that was just conscription service. But now — to fight in Ukraine?!»

In September, she received a call from the village council: «Your eldest son is on the list to receive a draft notice». That’s when Anastasia says she «lost it»: «I called the draft board, I screamed: my sons will not be murderers! Don’t even come close to them, or I’ll blow you up and burn you! They are not going to this war!»

We shed some tears and made a decision: the eldest would leave for Kazakhstan.

After the protest at the Bohdan Khmelnytsky monument, Anastasia was taken to Omsk Police Department No. 9, where she was held for about eight hours. A trial took place on the same day: under the article on allegedly discrediting the Russian army (as per Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code), Anastasia was fined 30,000 rubles (~ US$ 330), and and an additional 2,000 rubles (~ US$ 22) for purportedly resisting arrest (under Article 19.3 of the Administrative Code).

«They told me: „You must’ve been paid, you couldn’t have come up with this idea yourself“, — Anastasia is recalling her stay at the police station, — ‘and you couldn’t afford the poster, who sponsored you? ’. A policewoman said: 'Navalny that you support will croak! ’ And I told her: ‘He will become President! ’»

«Another one said: „Why are we babying her? She’ll be shouting ‚Glory to Ukraine! ‘ any moment now“».

«I immediately responded: „Glory to the heroes!““

«„Fuck!», he exclaimed, grasping his head!»

«I live in a free country; with my time ticking away, must I tremble at every turn? I do not know fear, do you understand?»

The day after the picket, a police car arrived at the Gordienkos’ house. Officers demanded that Anastasia write an explanatory report, stating that she wants to «set someone on fire or blow them up». Astonished, Anastasia didn’t immediately realize that someone had reported the phone call made a month prior. The police threatened to initiate a case under extremist or terrorist charges, but fortunately, they did not.

«I’m already an experienced fighter», Anastasia says triumphantly.

Her husband is no less of a fighter. «I once was in the political opposition but circumstances turned me into a revolutionary», sighs Sergey. «A peasant who’d fed the people all his life became an oppositionist — quite the twist, isn’t it?»

Political disagreements led Sergey to stop speaking to his own brother. His brother lives in the village of Gannovka and, according to Sergey, refers to the Gordienkos as fools while supporting the «Special Military Operation». His grandson headed off to Ukraine as a contract soldier and was awarded for his military service.

«I tell him: one day your grandson will be ashamed of these medals and will hide them. The people of Ukraine curse you for what you have done», sighs Sergey. «Propaganda has played its role, though we scarcely had time to take notice, did its job, but we didn’t have the time to guard from it. Lies and hatred pour from TV screens, but we were raised in this culture: our father is Ukrainian, we read Ukrainian magazines, sang their traditional songs».

Chapter Five, in which the Gordienkos annoy everyone

In 1988, the Gordienkos returned to Reshetilovka, only to find that the village and its only road to the rest of the world had officially ceased to exist. They arrived at a barren land. While building the house, they lived in a tent, managing until the cold set in. They built a farm, acquired livestock — they had fifty cows, as well as pigs, goats, sheep, and poultry. They became a family of six — by that time, Gordienko already had four children — two daughters and two sons, who now live separately with their own families: in Gannovka and Omsk.

For many years, the herd on the Gordienko farm set records for milk production — seven thousand litres of milk per cow each year. Awards marking their achievements are now stacked in the cupboard. In 2010, the family farm was awarded a silver medal from VDNKh (The All-Russian Exhibition Centre in Moscow). The couple fed the entire district with their milk, sour cream, cottage cheese, and eggs.

«We have hardly had a peaceful year here — we’ve had to fight all the time ever since we started farming», says Sergey. — «I wanted to make the farm business adequate, hoping for some assistance from the state. However, with milk prices plummeting, we could barely cover daily expenses, let alone invest in mechanization. So, we turned to loans, purchased equipment, and toiled tirelessly to repay these debts — thirty years of relentless effort».

In the 2000-s they began to travel to Moscow as they attempted to get loans promised by the government under the national project. Then they began to work towaeds an official status with Anastasia even resorting to a hunger strike outside the regional government building. Despite local media reporting that the governor pledged to address the matter, the issue remained unresolved.

«We’re residing in an unlawfully constructed dwelling. While we’re recognized as residents of Gannovka and dutifully pay taxes, we’re denied access to essential services», Anastasia explains. — «We are registered on the land in Gannovka, and our children lived in the house with their grandmother until they graduated from school. Though the house has long been dismantled, correspondence continues to arrive at this address. While our farm is registered, we’re told, „You can work here, but you can’t reside here“».

In late August 2014, the couple embarked on a milk truck journey to Omsk, Siberia’s second-largest city, heading towards the governor’s residence. The vehicle bore a message painted on its side: «Let’s pour milk under the governor’s feet». Ultimately, 500 litres of milk were emptied into a drainage well system.

During another protest calling for the governor’s resignation, the couple arrived with roosters and a goat in tow. The crowd chanted, «The police are against goats! The police won’t let the roosters in!»

During one of the pickets at the regional government’s building, Anastasia, freezing, helped a cleaner break the road ice. As a result, she was reported to «emergency psychiatric help». On her outpatient card, the reason for the call was documented as «snow clearing near the government house».

The doctor said: «You’re annoying them».

The Gordienkos say that they were inspired by European farmers — «we watched them fight for their rights in Germany, then in France».

They began to plan a new protest, intending to bring the governor not milk, but manure. However, their plans were cut short: a month after the milk campaign, a criminal case was initiated against Sergey under the charge of «fraud on a particularly large scale» (Article 159 part 4 of the Russian Criminal Code).

Sergey received a 2.5 million rubles grant for the modernization of his farm. However, in 2012, a drought hit. Faced with the dilemma of whether to slaughter their cattle due to lack of feed and proceed with farm modernization or saving the animals and postponing modernization for at least a year, Sergey chose the latter. Then there was a search in the house, which by law does not exist. During the trial, the prosecutor sought a 10-year prison sentence for «endangering society». As a result, Sergey was given a five-year suspended sentence.

«A farmer who has been feeding the people for 30 years, suddenly gets imprisoned!» Anastasia huffs. — «I repeated it like a mantra: Sergey, we have an acquittal rate of around 0,01%, and you will fall into minuscule fraction».

The family decided to fight back. They filed an appeal to the regional court, which overturned the decision. The family received compensation: 100,000 rubles (~US$ 1080) for moral damage and along with the reimbursement of 300,000 rubles (~US$ 3255) spent on legal fees. However, the toll of the trial weighed heavily on Sergey’s health. He developed asthma, which now forces him to frequently cough and rely on an inhaler.

Keeping the farm afloat became increasingly difficult and in 2017, the Gordienkos sold almost all livestock — Only three cows, two bulls, a piglet, goats, sheep, and poultry remained. The couple’s combined retirement pension amounts to just 17,000 rubles (~US$ 185).

«I hate this state for what it has done to me», Sergei says hoarsely. — «Our authorities are vile and despicable. They destroy people by all means and methods. They destroy people through any means necessary. When they couldn’t break me, they turned to my wife. Yes, she’s audacious and persistent, but she always fights for the truth».

Chapter Six, in which Sailor, Borka and Madame appear

In the mornings and evenings we have to feed and water the cattle, milk the cows, remove the manure, bring coal into the house, and cook food. The Gordienkos, with the help of relatives, built a huge barn. Geese and ducks live by the entrance, and the barn fills with qacking as soon as we enter.

The black bull, Sailor, playfully licks the camera lens with his warm tongue, while his unexpectedly warm horns press against it. Nearby, Madame the cow sports a curly crest, having recently birthed a calf named Sima, who nervously hops about in the cubbyhole on slender legs. In the darkness, the boar, Borka, awakens with an angry grunt, fumbling about with his massive snout. Amidst the commotion, goats and sheep fuss, and cows moo softly.

«I observed the way farmers live in Norway and attempted to be like them, but I couldn’t as the government shamelessly squandered millions», Sergei says, leaning against the wooden frame of a shed. — «I sent my son to Germany, and upon his return, he said: „Daddy, it’s not the same there. While there, work brings joy; here, it brings tears. The peasant is treated like a beast of burden, endlessly toiling in the fields“. The [Russian state] destroyed the village life. Villages lie in ruin, with countless vacant houses haunting the landscape.»»

Due to her husband’s health problems, Anastasia now has to carry around fodder and manure. Previously, a local hospital was within their reach, but now they must rely on an ambulance from Odesskoye. The weather often prevents the EMTs from reaching Reshetilovka, doctors have to walk there. It took eight hours to get to Sergey when he had a bout of intestinal obstruction. At the scene, they realized immediate hospitalization was necessary; a tractor had to clear the road before the car could pass through. This is why the couple are fighting for settlement status for their invisible village as it would mean state funds for a decent road.

«People are dropping like flies and yet still voting Putin», grumbles Sergey. «Our friend’s husband suffered a heart attack, but with no intensive care unit in Odesskoye, we rushed to Omsk, only for him to diepen route. Yet, she insists, „Who else but Putin?“ I told her, „Can’t you see? If there had been an ICU and a hospital in the village, your husband might have survived“».

Chapter Seven: Calm After the Storm

In the morning the invisible Reshetilovka is quiet and empty, with birds singing occasionally. The air is crisp and cold, with temperatures below 36 degrees Celsius outside. The storm has calmed down. Anastasia gets up at dawn and tends to the animals. She comments on our scant clothes: «Freezing your ass off is whatever — but if your ass’ neighbour freezes that’ll be a big problem».

Anastasia trudges through the snow with a crutch, as she had an endoprosthesis surgery on one leg and is waiting for the same on the other. There are 5,769 people ahead of her in the waiting list, with an estimated wait time of five to seven years. After taking care of animals Anastasia heads to the stove. For breakfast, she makes pancakes from fresh cream and homemade cheesecakes from cottage cheese.

Since the previous night, Sergei has been feeling unwell. He didn’t even have the energy to tend to the animals in the morning, weighed down by his somber thoughts and memories.

While Sergei and Anastasia’s children with other relatives occasionally visit their home in the non-existent Reshetilovka, during winter the couple typically find themselves alone. They have a lot of things to do, leaving little time for reading books and news, but both remain well-informed about politics. Anastasia has actively participated in numerous rallies advocating for the release of Alexei Navalny, and in the spring of 2021, she stood with a poster demanding his freedom.

«I sometimes turn on the TV, only to feel disgusted afterward. I prefer watching news on YouTube and subscribing to independent media. Navalny is my hero». Anastasia says. «We’ve had our disagreements with each government: Brezhnev’s, Gorbachev’s, Yeltsin’s, but this one is the most despicable».

In September 2023, police cars arrived at Gordiyenko’s house once more: FSB officers, a local officer from Odesskiy, police officers, and witnesses. Anastasia was informed that she was being accused of repeatedly discrediting the army, under Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code.

«Such an arrogant policeman, waving his badges, comes in and says, „Well, it’s obvious, you stole two and a half million and built a house“. We worked for so many years, and kept so much livestock!» she recalls.

The police demanded handcuffs. The local officer, who know Anastasia, blushed. No handcuffs were found. A state-appointed lawyer arrived in a car with the pro-war Z mark. Upon seeing this, Anastasia glared angrily and firmly stated that she doesn’t need such a lawyer.

The woman now has an OVD-Info affiliate lawyer — Andrey Ognev. According to him, Anastasia is still considered a suspect, there is «no specificity» in the case, and «the investigator has not presented the investigation and [linguistic] expertise for review».

We only know is that the case was initiated due to anti-war comments on «Odnoklassniki» social network. At the onset of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in the village of Gannovka, a «patriotic» car rally was organized. Local residents began weaving camouflage nets, knitting socks for the front lines, and casting trench candles. Meanwhile, in Odesskoye, funds are being raised for «assistance to Russian army soldiers».

Anastasia texted in many local chats, expressing her condemnation and disbelief at how ethnic Ukrainians could support the Russian army’s invasion of Ukraine, referring to them as «barbarians». In response to outrage, she stated that her sons and grandson would never participate in this war: «…we will go underground, become partisans, go to prison!»

«We simply laughed at propaganda and underestimated what it could do», adds Sergey. «They’ve even fallen out with their relatives from Ukraine. And some, like this guy from Generalovka, they call him Lava, he comes and says, „Our guys headed off to participate in the Special Military Operation, well done! Otherwise, we’ll end up washing the Americans' feet“. I say, „You can’t even wash your own feet!““

During a conversation about the war, the Gordienkos recall the son of their acquaintance, Andrey Kisly, who, according to them, didn’t want to go to war but ended up there because he was serving on contract. «He really didn’t want to. He died two months later», sighs Anastasia. Near the school in the village of Gannovka where he studied, graduates installed a memorial plaque. «Funds for it were collected by friends, classmates, and concerned residents».

Evgeny, who picked us up from Odesskoye, urges the couple to leave the country. In her usual manner, Anastasia rebuffs him, saying, — «Oh, go take a hike! I’m not going anywhere». But for Sergey, all of this is very difficult. He worries that his wife will be imprisoned. They both say that it would be a death sentence for him.

Chapter eight, in which «Kalynonka» sings

When the Gordienkos lived in Gannovka, Anastasia worked there as the director of the House of Culture and gathered a Ukrainian song ensemble. At first, it did not have a name, but later it was named «Kalynonka». The members of the ensemble went on tours and performed at the local House of Culture.

We arrive at this House of Culture and notice a reproduction of famous Russian painting «Zaporozhian Cossacks» right at the entrance. It depicts a scene from the 1760s conflict between the Ukrainian Cossacks and the Ottomans. Beneath the painting stands a notice board with the letter Z, the inscription «Heroes of our district», and fourteen sheets with the names and photographs of those who died after February 24, 2022. Ovcharenko, Rudenko, Kisly…

We walk into the recital room to the sound of the Kalynonka performers singing a folk song. Seven elderly women in folk costumes are singing their hearts out, unaware of our presence.

«What if they don’t understand us?» — one of them says to another in Ukrainian.

«They will, why wouldn’t they?» — another one answers, also in Ukrainian.

Practically all of them are ethnic Ukrainians — descendants of settlers who have preserved their native language and culture. Only Maria is Russian, but she says she enjoys singing in the Ukrainian ensemble, even though it’s sometimes difficult to understand all the words. Her Ukrainian husband helps her with that. We don’t immediately realize that she is the wife of Yuri, Sergey Gordienko’s brother, who stopped communicating with him after February 24, 2022.

«Our grandchildren speak mostly Russian, but our children can also speak Ukrainian! As for us, we love both languages», says Valentina Kolbasa. She is talkative and giggly, sitting in the middle. «When I used to go to retreats in Russia, people would encourage me to speak Ukrainian and say that it sounds very interesting!»

From Gannovka, 9 people went to fight in the war, one has already died — Valentina Babak’s nephew. Lyudmila’s son is on the front lines. Maria’s grandson is there now, and Valentina Kolbasa’s grandson-in-law. Valentina Babak helps soldiers — she weaves camouflage nets, while Maria Yakovlevna knits socks for the front lines.

«And what else? My granddaughter Nastya’s husband was taken to the front», — Kolbasa shares, speaking in a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian. «My heart is aching for everyone, but I specifically don’t want to lose someone from my own family. But what else could we do? How could he refuse to go? He’s eligible for military service. It’s better to fight than to be in jail. That’s what I think».

In Ukrainian, she continues: «on TV, they say our troops are killing — what they call — „Banderites“. But how many of our own people are dying! I listen to „60 Minutes“, but I hate Solovyov, forgive me, Lord, for saying so, they’re spreading propaganda. We don’t understand politics and don’t want to get involved, really».

Many here still have relatives in Ukraine, but they barely communicate.

«They’re putting the blame on us», Valentina continues. «The thing is, our people who call Ukraine say they don’t want to talk anymore, like, „You betrayed us, you sold out to the Muscovites“ — they saw „Z“ on our T-shirts».

«They must have such propaganda and politics there that they speak ill of us», someone among the women adds.

They talk of «Banderites» and «the rise of Nazism in Ukraine», recalling TV-programs on the state-owned channel «Russia 1», but then everyone unanimously says that they are eagerly awaiting the end of the war.

«In 2014, they took my son there, he served in the OMON», says Lyudmila Vasilyevna, a woman with black hair peeking out from under her scarf and beautiful deep eyes. «Then in 2022 — there again, he was there for three months, got concussed. Now he’s on a pension — 18,000 rubles (~US$ 185). It’s bleak. He’s been concussed twice. And where do we turn? Mom says, calm down. They told him: you’ll be doing cleanup. They captured the village, and then they needed to clean it up. And their entire unit got bombed. And they didn’t pay them anything. Only the pension».

«That’s what I say: the poor are the ones who have to go to war, and try to earn a living. That’s the truth!»

«No, why, Valya, that’s not true!» — Maria immediately responds. — «They show it in the programme „Nashi“ [Ours] on the second TV channel. It’s my favourite programme, I always watch it, there are so many of our guys fighting there: Kazakhs, Ukrainians. And they all return from there and say: „Look what is happening there, how they have been tormenting people there since 2014“».

«Who do you feel like you identify with more?» — I ask.

«Russians!» — Maria says. — We are Russians».

«And I was and will always be a Khokhol, why would I be Russian?» — Valentina Kolbasa says with a smile.

«What’s that have to do with it! Valya, come on! Why do you even live here then?!» — cries out Maria. And immediately adds: «We have many ethnicities here, all living peacefully. We all live and drink tea together».

When asked about the Gordienko family, she asserts, «There’s never been, nor is there any splits among families in the region». According to her, her husband and brother have not seen each other for a long time: «When should they meet? We have a farm, and they have a farm to take care of».

We continue to talk with the women about the war, culture, their relatives, and rural life. Now they perform less and less often because of ageing, it has already become difficult. But today they’re singing a Ukrainian folk song:

When they found out — they chirped away,

When they found out — they chirped away,

If only they didn’t know happiness.

Close neighbors — hard enemies,

Close neighbors — hard enemies,

Close neighbors — hard enemies.

Chapter Nine, in which we argue with the governer of Gannovka

Marina Sayun is the governess of Gannovka. As Anastasia Gordienko recounts, she and Sayun were once close friends, they used to go to Odesa together, attend theatres together. But then «she went into government—and that was it».

At first, Marina avoids meeting for a long time. Eventually, she reluctantly agrees, albeit briefly and without allowing photography. When we finally meet in her office, she nervously fidgets with the documents on the table and appears visibly uncomfortable.

Sayun has been governing the settlement for 20 years since 1986 when «there were more yards, but then the youth, striving for a better life, began to leave». According to the latest census, 690 people are registered in Gannovka, but according to Sayun, many are only registered here, and no longer live in the village.

«Gordienko? I don’t keep in touch with her», Sayun says. «But I know she held a solitary picket against the „Special Military Operation“. I don’t think that’s quite right».

Once more, familiar themes emerge about «the confrontation between Russia and the West», with references to Vladimir Solovyov and Tucker Carlson’s interview with Vladimir Putin.

«Working is tough», she adds when we discuss life in the village. «If there were sufficient funds in the budget, it would be much easier. But with so many responsibilities and limited resources, it’s challenging. We’d like to accomplish much more».

«And then», — she continues, — «Half of the people here speak Ukrainian. Just go to the store and listen. And they also speak Kazakh. We have many ethnicities here. Speak whatever you want. No one prohibits it, unlike in Ukraine: „Speak only in Ukrainian“. They’re closing Russian schools there. What’s that all about?»

«Wait, but here we are fined for the Ukrainian flag and clothes in [supposedly pro-Ukrainian, blue and yellow] colors».

«No, we don’t have that and never did!» — she raises her voice. — «Where did you get that idea?! We even have a yellow and blue sports uniform, kind of yellow-blue. What’s wrong with that? I don’t understand. We all live in harmony here. No oppression, nothing like that. Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Russians — they sing Ukrainian songs on stage.

«Maybe everyone gets along, but the cops investigate [dissidents] nonetheless».

«In Russia? What nonsense! I don’t even believe it. Where have you seen such a thing? No, we don’t have that, what are you talking about?»

And though she admits she «doesn’t want to get involved in politics», — she bitterly acknowledges that she’s deeply hurt by what’s happening. After all, as she puts it, it’s painful when two brothers end up on opposite sides of the front: «It will take a lot of time because there are so many casualties on both sides. It’s not something that will be forgotten or forgiven in just one year», — she remarks softly.

Epilogue

«Every night I have the same dream. I meet Navalny, hug him, cry, and say, „My son“. It means we’ll meet. I feel everything will be alright, he’ll be released, and I’ll tell him, „I’m happier to see you than ever“. Just like I felt when they were trying Sergey».

These were the words Anastasia Gordienko said to us in mid-February — we arrived at their place on the 14th. On the evening of February 16th, we left Odesskoye towards Omsk. When the mobile connection was restored, we learned that Anastasia would never meet Navalny.

The next day, Zhenya texted us: «Auntie Nastya cried all night yesterday. Sergei started feeling unwell, he’s very down. In the evening, I’ll have to walk over to them».

Text: Marina-Maya Govzman

Photographs: Anya Marchenkova