Over the last months, more and more people persecuted for political cases have been reported to be regularly placed in a punishment cell (a so-called «SHIZO» in Russian). It happened not to Alexei Navalny, who has already spent 226 days in a punishment cell, but also to deputy Alexei Gorinov, politician Vladimir Kara-Murza, left-wing activist Daria Poliudova, journalist Maria Ponomarenko, Alexei Moskalyov (father of Masha Moskalyova), and other convicted people.

Lawyers, human rights activists, and journalists are sounding the alarm: this confirms that treatment of political prisoners has worsened since the war started. OVD-Info gathered all known cases of prisoners placed in a punishment cell in 2023. Learn more about how much time they spent in punishment cells, the «misdemeanours» they were sent there for and how having spent time in a punishment cell can pose a threat even after their release.

Number of people persecuted for political cases placed in a punishment cell

In 2023, at least 40 people sentenced for politically motivated cases were sent to a punishment cell. On average, they spent 15 days there. Many were placed in punishment cells several times over: we are aware of 82 such cases, and the length of time spent in a punishment cell is known for 65 of them. An incomplete total for 2023 is 1,015 days spent by political prisoners in punishment cells; that is, almost three years.

In 2023, defendants in the Hizb ut-Tahrir case were placed in punishment cells most frequently; we know of at least 13 such people. Those sentenced in cases related to Jehovah’s Witnesses were also sent to punishment cells — there were at least 6 such people in 2023. Among the defendants of the «anti-war case, » at least 4 people were sent to a punishment cell, each of them more than once:

- Alexei Moskalyov — 5 times;

- Alexei Gorinov — 3 times;

- Maria Ponomarenko — 3 times;

- Vladimir Kara-Murza — twice.

Even though the maximum allowed term in a punishment cell is 15 days, many prisoners were kept there for months: their terms are regularly prolonged under the pretext of various misdemeanors. For instance, a defendant in the Yalta Hizb ut-Tahrir case Muslim Aliev spent a total of at least 120 days in a punishment cell in 2023. Timur Yalkabov, a defendant in the third Simferopol Hizb ut-Tahrir case, spent around 87 days in a punishment cell.

Vladimir Domnin, a defendant in the «Right Sector» case is among the «record holders: ” he was sentenced to 9 years in a strict regime penal colony, and throughout 2023 he was sent to a punishment cell 8 times for 69 days in total. Former head of Serpukhov district of the Moscow region Alexander Shestun was sent to a punishment cell 6 times for more than 60 days altogether.

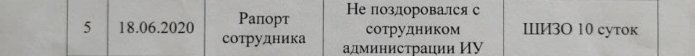

The formal reason for placing an inmate in a punishment cell is the violation of internal regulations; however, in reality the corrections officers would use any pretext to isolate the inmate. Here are the reasons for placing political prisoners in punishment cells in 2023 (based on cases where the reason is known):

It is complicated to collect exact data on placing political prisoners in punishment cells. Inmates often don’t have the opportunity to describe the conditions of imprisonment and the federal institutions are becoming more and more secretive: the Federal Penitentiary Service stopped publishing even archive data on the imprisoned population.

What is a punishment cell (SHIZO): cold, humidity and a toilet under video surveillance

A punishment cell is located in the same penal colony where a person is sent to serve time after being sentenced and going through the appeal process. Inmates are sent there for 3 to 15 days, but the term may be extended many times. What is a punishment cell? Here are the descriptions from political prisoners who have already been released:

- «There was no hot water in my cell. The toilet was next to the eating area, not separated from the main part of the room. Two surveillance cameras kept a watch on the entire cell, including the toilet. There was no button to call the corrections officer on duty. The ventilation malfunctioned, resulting in an uncomfortably hot room temperature. Rodents occasionally found their way into the cell.» This was an excerpt from the complaint filed by civil activist Konstantin Kotov, convicted under the «Dadin» article. He was initially sentenced to four years for participating in peaceful protests. But later his prison term was reduced to one and a half years upon appeal. Kotov was transferred to a labour colony in Pokrov, a town about 100 km away from Moscow. He was subsequently released in December 2020.

- «It is a premise not bigger than your bathroom, just a couple of steps forward and a couple of steps back. My punishment cell was six steps long and four steps wide, ” recalls Andrei Borovikov, former head of Navalny’s headquarters in Arkhangelsk. He had protested against the construction of a landfill at the Shiyes station, located 1,200 kilometres north-east of Moscow. Borovikov was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for sharing Rammstein’s „Pussy“ music video on his social media. He was transferred to Corrective Labour Colony No. 7 in the Arkhangelsk region, where he was regularly placed in a punishment cell. Borovikov was released in May 2023.

- „I could leave my cell for only one hour a day to take a walk in the courtyard, which was not larger than a [punishment] cell, if not smaller. I spent the remaining time in an almost empty cell. There was just a metal table, a stool, and what is usually referred to as a „shkonka”– a type of bed that is folded up against the wall during the day. And that was it. Furthermore, one was not allowed almost any personal belongings except writing materials, soap, toothpaste and a toothbrush, ” says Ivan Astashin, a human rights activist and contributor to the Solidarity Zone project. Back in 2012, he was found guilty in the so-called „ABTO case“, landing him with a 13-year sentence within a strict regime penal colony. His term was later reduced to 9 years and 9 months. Astashin was transferred to Corrective Labour Colony No. 7 in Siberia’s Krasnoyarsk region, where he endured more than 20 stints in solitary confinement. He was released in September 2020.

- «In the cell there was a table, sometimes merely a shelf on the wall, scarcely large enough to fit a plate; a sort of a stool and a bed that could be unfolded from the wall solely during the nighttime. My main issue is a troublesome back. Sitting all day was too painful, as was standing. So, from time to time, I lay down on the floor. The floor remained bitterly cold even in summer, but I had to change my position. Officially, it was prohibited to lie down in a punishment cell during the day, but by then, I couldn’t care less, ” reflects Olga Bendas, a person involved in the „Palace case“. Following a two-year prison sentence, she was transferred to Corrective Labour Colony No. 3 in the Ivanovo region, located around 290 kilometres from Moscow. There she was constantly placed in a punishment cell. Bendas was released in August 2023.

While in a punishment cell, prisoners are not allowed to be visited by their family, nor can they receive parcels, use personal belongings, or seek medical attention. In a punishment cell, it is even forbidden to smoke while walking. As Kotov recalls, «These conditions are among the most restrictive that one can experience within a prison».

All OVD-Info interviewees say that the main difficulty in a punishment cell is the coldness. «The temperature there is about 17-18 degrees Celsius (63-64 degrees Fahrenheit). The trick is that when you spend a day, or two, or three days at this temperature, you really feel how your body freezes. All you want is to warm up, ” says Andrey Borovikov.

Ivan Astashin recalls his days in a punishment cell in the Krasnoyarsk penal colony this way: «First you walk around the cell to warm up your legs. Your feet get warm, but your head becomes cold, so you climb into your jacket with your head down. I warmed my head, but by then my feet got frozen again.»

Crimean journalist and human rights defender Lutfiye Zudiyeva told OVD-Info about what is going on with Emil Dzhemadenov, a defendant in the Simferopol Hizb ut-Tahrir case, who was sentenced to 11.5 years in a strict regime penal colony. «For the 21st century, this sounds very scary. Emil’s wife said that when her husband is in a punishment cell, he is forced to constantly change his socks: they get wet because he is in a damp concrete room. Health rapidly deteriorates in such conditions, ” says Zudiyeva.

One of the few rights of a prisoner that remains in a punishment cell is the chance to meet with an attorney. In addition, in a punishment cell you are allowed to read books and answer letters for an hour a day, says Konstantin Kotov.

Why do people get sent to a punishment cell?

The punishment cell is a tool to put prisoners under pressure. «The administration of penal colonies wants inmates to submit to any, even illegal, demands and not try to defend their rights, ” explains the head of the „Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial“ project Sergei Davidis. This is also evidenced by Olga Bendas: in her words, she was regularly sent to a punishment cell for „denying the regime.“ She deliberately refused to work for the Federal Penitentiary Service for an average salary of 200 rubles per month.

It is easy for penal colony staff to find a pretext to place a prisoner in a punishment cell. Often very minor violations are used for this. For instance, Andrei Borovikov was sent to a punishment cell for drinking water for too long and putting a half-eaten piece of bread in his pocket, and Konstantin Kotov for incorrectly introducing himself. «It is precisely for such reasons that people are formally sent to a punishment cell. In fact, almost no one fulfils these requirements: there are so many of them and it is so difficult to keep track of them that they get violated all the time. But if the [penal colony] administration wants to find fault with you and make your conditions worse, they will take advantage of this, ” says Kotov.

The specific criteria by which one can assess the severity of a violation and decide whether to send a person to a punishment cell are not laid out anywhere, explains OVD-Info lawyer Vladimir Bilienko, who defends Alexei Moskalev. «This is decided by a corrections officer who writes a report and sends it to the commission, where they make decisions about sending the prisoner to a punishment cell. How the „violation“ is assessed is highly subjective. An officer, especially if he was specially instructed by his boss, can turn the life of a prisoner into a kind of hell, ” says Bilienko.

«Particularly ‘inconvenient’ prisoners can be tortured by being repeatedly sent to a punishment cell at the request of high-ranking bosses, including those in the government and law enforcement agencies, ” suggests a staff member of the „Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial“ project, who wished to remain anonymous. „Perhaps this is a request from the leadership: in the case of Navalny and Kara-Murza, this may be directly related to Putin. Or maybe with other high-ranking people who had problems due to anti-corruption investigations or for being put under sanctions. In some cases, perhaps these are some agency’s interests, as with [deputy Alexey] Gorinov and [Moscow State University PhD student Azat] Miftakhov. You can initiate more and more new criminal cases, but the easiest way is to place them in a punishment cell and report that the person has been repressed to the maximum extent possible, ” notes the human rights defender.

Staff of the penal colonies are wary of inmates with media prominence and public support, says Sergey Davidis: «They’re always on guard in case something happens, in case they get in trouble for a public statement made by someone from the colony. Often, as a preventive measure, as was in the case of Vladimir Kara-Murza, they send the inmate to a punishment cell. This probably demonstrates that they don’t condone [the prisoner’s communication with the outside world] and have taken all possible measures, ” suggested the human rights defender.

Another purpose of sending someone to a punishment cell is to worsen the inmates’ confinement conditions. If an inmate is frequently placed in a punishment cell, they may be declared a «persistent violator» and face stricter confinement conditions.

This is what happened to Andrey Borovikov. He was sent to a punishment cell four times for minor «violations» that other inmates committed without consequences. Subsequently, he was placed under strict confinement conditions («SUS» in Russian). There, inmates spend up to 9 months: they are kept in separate cells of a barrack, separated from the residential area, and cannot apply for parole.

«The administration staff said: ‘It’s an order from above; sorry, Andrey. We were told to place you under strict confinement conditions so that, upon release, you would be under supervision.’ And they got their way, ” Borovikov emphasised.

Other ways of worsening the conditions of detention include placement in a cell-type room («PKT»), and then in a single cell-type room («EPKT»). The single cell-type room is often called a «prison within a prison: ” „It’s a separate ‘roofed’ area for ‘persistent violators’ that is set up and operates under its own set of rules, ” as described in „Novaya Gazeta. Europe.“

The repercussions of being sent to a punishment cell, SUS, PKT, and EPKT haunt the convict even after their release: it becomes grounds for administrative supervision. For instance, Andrey Borovikov has been given two years of supervision: he visits the police twice a month to check in. Ivan Astashin was assigned administrative supervision for 8 years. After his release, the pressure on Astashin continued: he was interrogated by officers from the Center for Combating Extremism, and the police visited both his parents and the landlady of the room he rented.

Women in punishment cells

Before the war in Ukraine, the Russian state tried not to imprison women persecuted for political reasons, notes Sergey Davidis, the head of the «Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial» project. Now, this happens more frequently.

«With the onset of the war, patriarchal standards of some leniency towards women began to crumble. And since a woman, just like a man, poses a threat to the authorities, these sentiments are discarded: women too are being imprisoned for long terms, ” says the human rights defender.

There is a difference between punishment cells in male and female colonies — and a significant one. «Male and female colonies are simply worlds apart. The female colony is hell in the literal sense of the word, and the punishment cell in a female penal colony is hell within hell, ” says Olga Bendas, a defendant in the „Palace Case.“

While men are allowed to stay in a punishment cell in their clothes, women are literally undressed there: according to Bendas, they are in underwear, a shirt and rubber slippers. «Imagine being thrown outside for 15 days in winter in your underwear and a shirt. The temperature [in the punishment cell] is absolutely the same, ” she says. This is how the woman describes the next 15 days in a punishment cell, which were her most terrible period of time during her stay in the colony:

«It was May. It seemed to be warming up a bit, so the heating was turned off — that’s it, spring. And then the snow falls, and we are back to winter weather. In the living area, everyone put on fofan (warm jackets), warm scarves, and boots. And they shut me in the punishment cell: on the second day, I was already saying goodbye to life. To say that it was cold would be an understatement.

You can’t sit on anything, because everything is icy: a metal stool and a metal table screwed to the floor. The fact that you don’t move makes your body swell, your blood stops circulating — it doesn’t warm you. I had cramps all over my body, I couldn’t bend over: I was curled up on my knees and sat like that for 15 days.

After lights out, they bring in a mattress, you go to bed. But everything is icy to such an extent that the problem [with cold] is not really solved. We were given two waffle towels together with this shirt, about 30 by 30 centimetres. And I tried to wrap these towels around my feet to keep warm, so that at least at night I wouldn’t get cramps. I would wrap them up, and then I would lie down, but everything would unravel — and so the whole night I did nothing but wrap towels around my feet. It was the worst 15 days: I was really carried out of that place.

Another problem that can be encountered in a punishment cell is violence. Video cameras do not help, says Olga Bendas: «We are always under surveillance cameras, but they can do anything to you and then just erase the tape. Who are you going to prove anything to? These cameras are not for us, these cameras are for them.»

Sasha Graf, author of the Zhenskiy Srok («Women’s Prison Time») podcast, notes that less is known about the extent of violence in female prisons than in male ones because women have less support. «About as little as five percent have paid lawyers who can regularly visit a prisoner and defend her rights. It is difficult for women to do this on their own; if you write a complaint, the administration will find out, and you may be sent to a punishment cell. Women are left helpless against the FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service) system, they have nothing with which to counter the huge machinery, ” says Graf.

According to her, the most common reason for putting women in punishment cells is their refusal to work. «It should be understood that the prisoners [women] are in fact in slavery of the FSIN; they work in two shifts, receive pennies, and work to exhaustion. At some point, their organism simply cannot stand it, and if you dare to defy the staff, it’s a direct way to a punitive cell, ” explains the author of Zhenskiy Srok (Female Prison Term).

Another reason for sending women to punishment cells is to intimidate prisoners who are in romantic relationships, says Graf: «Usually, staff turn a blind eye to this, especially since women often manage to hide. But at the right moment, staff can use this as a motive. Also, the threat of a punishment cell or being placed in one can put pressure on the prisoner’s partner.»

In 2023, at least two women who are being persecuted for political reasons were placed in punishment cells: Daria Polyudova, the creator of Left Resistance, and Maria Ponomarenko, a journalist with the RusNews project.

Poliudova is serving 9 years in Corrective Labour Colony No. 4 in Kabardino-Balkaria (a region in southern Russia). She said that a razor was planted in her belongings upon her arrival in the prison; this is why she went on a hunger strike. The activist was nevertheless placed in a punishment cell — for the razor and for one more violation, says Tatiana Poliudova (Daria’s mother). All this led to Daria being placed under strict confinement conditions for six months.

During her recent conversation with OVD-Info, Tatiana Poliudova shared some details about her latest visit to her daughter. Daria talked about the planted razor and the punishment cell. Tatiana conveys Daria’s words: «Mom, I’ve never seen how they make razors [in prison], they must take something apart to get them, shaving razors probably, I don’t know.»

Political activist and journalist Maria Ponomarenko was sentenced to 6 years in prison for distributing «war fakes» (subsection «e» of Part 2 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code). The grounds for charges against her was a social media post about the bombing of the Dramatic Theatre in Mariupol by the Russian military.

During her time in pre-trial detention, she was unlawfully placed in a psychiatric hospital and a punishment cell, and also survived a mental breakdown and a suicide attempt. Upon her arrival in Corrective Labour Colony No. 6 of Altai Krai (a region in southwestern Siberia), she was placed in a punishment cell for three prison rule violations reported by corrections officers. The first time, Maria reportedly insulted the corrections officers. Ponomarenko fainted, and this was considered a second violation: that happened when, according to the corrections officers, she was resting during the daytime and thus violated the prison rules. Ponomarenko did not get any medical attention after she fainted and fell. The third «violation» was the journalist’s inability to get up from her bed upon a corrections officer’s demand due to severe pain in her lower back.

First, Ponomarenko was placed in a punishment cell for 15 days, then for another ten. In addition, she is not given letters, medical care, and is not allowed to submit complaints about violations by the colony staff to her lawyer Dmitry Shitov, who cooperates with OVD-Info. On October 17, the journalist was reported to have been placed in a punishment cell for 15 days again.

Defendants in Hizb ut-Tahrir cases are regularly placed in punishment cells

Hizb ut-Tahrir is an Islamist party which the Supreme Court recognised as terrorist in 2003. Human rights activists emphasise that the court decision does not contain any evidence of terrorist activities committed by the association. The decision became a reason to prosecute its alleged followers in Russia and annexed Crimea. In particular, it affected the Crimean Tatars. At least 335 people are being prosecuted for their probable involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, reports «Support for prisoners. Memorial». Most of them — 271 — have already been convicted: 128 received sentences of 10 to 15 years, and 115 received sentences of 15 years or more.

According to OVD-Info, in 2023, the defendants in Hizb ut-Tahrir cases were placed in punishment cells almost every month: some of them were not released from there for months, with the authorities regularly extending their detention periods.

First reports about placing the participants of the Crimean Hizb ut-Tahrir cases in punishment cells began to appear as early as 2019-2020, says a local journalist and human rights activist Lutfiye Zudiyeva. «These were the stories of Teymur Abdullayev and Emil Dzhemadenov, and their lawyers tried to challenge [their placement in the punishment cell] for a long time. And these were the first cases of such practices in penal colonies. It has now become practically everyday life. We regularly receive reports from relatives and lawyers of prisoners in this category of cases that they are placed in punishment cells. I believe that after 2022 this practice has become tougher, ” Zudieva said.

The defendants in Hizb ut-Tahrir cases are usually tried under a serious article on participating in a terrorist organisation (Parts 1 and 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code), so it’s easier to place them in punishment cells: this is how corrections officers report to the secret services that the inmates are under special control, and at the same time fulfil the «stick» on the number of inmates sent to the punishment cell, Zudieva said.

In her words, placement in a punishment cell may be related to a refusal to cooperate with the secret services: this was the case with Teymur Abdullaev, who has been in custody since 2016. He was sentenced to 16.5 years in a strict regime colony and was transferred to Corrective Labour Colony No. 2 in Bashkortostan. When FSB officers came to Abdullaev’s colony and demanded that he testify against other Crimean residents, he refused. After that, they began regularly sending him to a punishment cell. As of October 26, 2023, Abdullaev had spent 874 days in a punishment cell, specifies Holod, whose journalists reported about the persecution of the Crimean Tatar. Lutfiye Zudiyeva adds: «He practically lives in the punishment cell. He is taken out for some time when publications start appearing in the media and when there is a certain resonance in the society, with human rights activists getting involved. As soon as this attention fades, they put him back in there.»

Is it possible to appeal one’s placement in a punishment cell?

Both human rights activists and former inmates concur that seeking to appeal their placement in a punishment cell often turns out to be ineffective. By the time a hearing is arranged, the assigned time in a punishment cell has often already passed, and the courts tend to rule against the inmates. At the same time, each year sees a rising number of efforts to seek compensation for an unlawful placement in a punishment cell, as reported by Novaya Gazeta. However, Russian courts tend to consistently dismiss such complaints filed by inmates. Journalists have calculated that from 2012 to 2021, the courts have ruled in favour of only one claim in its entirety.

Nonetheless, offering help with appealing one’s placement in a punishment cell and providing other forms of support conveys to the prison administration that the inmates have not been abandoned. Sergei Davidis, the head of the «Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial» project, explains: «[At Memorial], we are actively engaged in offering legal aid to political prisoners, assisting them in challenging those placements in punishment cells. This is not always effective and often turns out to be rather ineffective, but it serves as an important gesture of moral support. This also acts as a certain constraining factor for the administration. Clearly, this strategy isn’t effective in Navalny’s case due to the involvement of the main state apparatus, but it may have a more positive impact for others.»

Lawyer Vladimir Bilienko stresses the significance of support, saying, «Whenever possible, it is better to visit the client in prison occasionally — to offer legal assistance and moral support.» Bilienko points out that this sends a clear signal to the administration that the individual has not been forgotten and that they must exercise greater care in their treatment.

It is crucial to file an appeal against having been placed in a punishment cell after release. In these instances, the court may sometimes rule in favour of the inmates. Additionally, it is important to document the violations by the Federal Penitentiary Service in court, as highlighted by Konstantin Kotov. His legal proceedings regarding the conditions of detention have been ongoing for three years. In one of the rulings, he was awarded 30,000 rubles (≈USD 320) as compensation.

Andrei Borovikov lodged appeals against his two instances of having been placed in a punishment cell, seeking compensation of 100,000 rubles (equivalent to approximately USD 1,068) for unjust persecution. The court acknowledged violations in both cases but only awarded a compensation that was 20 times less that amount — 5,000 rubles (about USD 53). In response to this, Borovikov wrote, «They refused, claiming I’m asking for too much. These… why don’t they serve those 10 days [in a punishment cell] themselves, and I’d happily give them 5,000 [rubles].»

How can we help?

Placing prisoners in a punishment cell is a long-standing and well-established systemic practice. According to individuals interviewed by OVD-Info, achieving substantial changes in this regard is impossible without an overhaul of the penitentiary system and, more broadly, without transformative shifts in the country’s political landscape.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t imply that prisoners, including those facing persecution for political reasons, should be left unsupported. Publicity remains crucial as it provides prisoners with a platform to voice their concerns and draw attention to the issue. Appeals to authorities responsible for overseeing detention facilities can also help.

Sending letters to prisoners can be a meaningful form of support. As the inmates themselves attest, in prison it’s very important to know that you haven’t been forgotten. Andrei Borovikov described the letters he received as a form of doping, stating, «When I didn’t feel well, when I was sick, I read the letters and was filled with energy.» He cherished all the letters he received and even took them with him after his release, saying, «I replied to all those letters, and there were several thousand of them.»

You can write to a political prisoner, among other means, using a Telegram bot created by Memorial, MediaZona, and the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK). This bot is built based on data provided by OVD-Info. It was launched on the eve of October 30, recognized as the Day of Political Prisoners. Human rights activists emphasise, «As of today, there are 610 political prisoners on our lists. Unfortunately, not every political prisoner has a high profile or a network of support. You can step in as a patron and join a network of support for some of them.»