Date of publication: June, 7, 2022

Текст на русском: Блокировки интернет-ресурсов как инструмент политической цензуры

Over the past ten years, blocking has become one of the largest tools for restricting access to information and freedom of expression. Although the first legislative changes expanding the possibilities of blocking and simplifying this procedure appeared back in 2012, there have still been very few studies and reports on the situation, and it has not received wide public coverage outside narrow human rights and expert circles for a long time. The lack of proper documentation of violations of international norms and human rights standards only contributes to the current situation — de facto complete Internet censorship in relation to alternative sources of information.

As has been repeatedly emphasized by various experts and institutions, the Internet is one of the key technologies for the rapid and decentralized exchange of information, where responsibility for the content of publications is also distributed among different units. This makes the Internet fundamentally different from traditional media. This, as well as the availability of technology to ordinary users, have made the web the main means of expressing opinions at the present time. Nevertheless, the authorities of different countries, including Russia, are trying to appropriate control over the Internet within state borders — they restrict the use of foreign servers, force large IT companies to open offices in the country, place equipment at cross-border exchange points that blocks certain sources of information, etc.

In this report, we consider blocking Internet resources as a tool of political censorship, connected, on the one hand, with the general policy of bans on freedom of speech in Russia, and on the other, with network technologies that are fundamentally different from traditional media. We consider online censorship in its dynamics: we compare the current situation of the war and the radical measures implemented to restrict freedom of speech in Russia, with the beginning of 2022, when all the main tools of online censorship have already developed, and also trace the history of the formation of legislative instruments and law enforcement practice of the last ten years.

The report is based on the following sources:

- Legislation of the Russian Federation affecting freedom of speech on the Internet (laws «On Information», «On the protection of children from harmful Information», «On the media», «On measures to influence persons involved in violations of fundamental human rights and freedoms» and others);

- Roskomnadzor documents (activity reports, press releases, etc.);

- The European Convention on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and other international documents;

- Practice of the European Court of Human Rights, opinions of the Venice Commission;

- Documents of the UN Human Rights Committee, the UN Human Rights Council, UN Special Rapporteurs, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the European Union, the Organization of American States, the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and other international organizations;

- The OVD-Info report «No to war. How Russian authorities are suppressing anti-war protests, » and other materials and data from OVD-Info;

- Reports of Russian and international NGOs on freedom of speech and blocks, other documents and statements (the project «Misuse of Anti-extremism» of the SOVA Center, the Net Freedoms Project of the Agora International Human Rights Group, as well as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Civil Rights Defenders, Reporters Without Borders, Accessnow, CIVICUS, Article 19, Freedom House, Censored Planet, and others);

- Data of the Roskomsvoboda project (register of blocked resources, news, expert comments);

- Publications of the Mass Media Defence Center;

- Publications in the media (RBC, Cnews.ru, news section of the OVD-Info website);

- A closed round table organized by OVD-Info with the participation of experts from the projects SOVA, Roskomsvoboda, Net Freedoms Project, and Mass Media Defence Center.

Blocking Internet resources in Russia

One of the main and obvious problems of resource blocking in Russia is its constantly growing scale. It was not always associated with political censorship, but it seriously affected the general possibility of expressing opinions and the development of civil society. The trend is perfectly traced by the increase in the number of blocked resources, as well as the reasons for such blocks. In fact, according to the Roskomsvoboda project, 261 resources were blocked in 2012, whereas in 2021, 63 554 resources were blocked at the request of the courts, and another 8421 — at the request of Roskomnadzor.

According to the Network Freedoms project, in 2021, there were more than 450 thousand specific cases of interference with Internet freedom in Russia (most of them — blocks) and more than 90 general initiatives on restrictions and bans on the Internet. These figures are enough to understand that blocks are a large-scale measure, the indicators of which have been constantly growing since 2012 and until February 24, 2022, when an avalanche of blocks actually destroyed direct access from Russia to non-state socio-political media. Moreover, the trends of recent years include not only an increase in the number of blocks, but also the criminalization of online activity, as the Net Freedoms Project writes in the report on Internet freedoms for 2020. Users are increasingly receiving fines and prison sentences for their texts, reposting other people’s materials and even likes.

The situation only worsened with the outbreak of the war. From February 24 to May 5, according to Roskomsvoboda, more than 3,000 sites were censored in connection with publications about the war (it is important that this statistic does not include blocking on other grounds). New bills restricting freedom of speech for both the media and citizens were introduced and came into force; many media outlets were blocked or dissolved; social networks were «slowed down» or declared «extremist» and banned. According to Roskomnadzor, about 120 thousand resources were also blocked, among which the RKN allegedly found not only «fakes, » but also sites with «Ukrainian nationalist propaganda with a total audience of over 202 million users.»

According to the list of blocked resources of Roskomsvoboda, the number of blocks from February 24 to May 26, 2022 increased for almost all agencies compared to the same period in 2021. In particular, a large increase is due to blocking by the decision of the Prosecutor General’s Office, that is, as a rule, related to the restriction of political freedoms.

The state information policy is still formally based on legislation, but the range of laws adopted in recent years allows authorities to block almost any page, website or media. The latest amendments proposed to the State Duma, if they are adopted, will allow Roskomnadzor to do this without a court decision, only at the request of the Prosecutor General’s Office — that is, lightning fast.

Blocking may not be the most painful way of infringing on freedoms, but it is definitely the most widespread. According to our roundtable experts, as well as to the results of the study of the most notable cases of blocking over the past two years, one can consider purely political the bans on «calls to participate in mass (public) events held in violation of the established procedure, » on the publication of materials of «undesirable organizations, » and after the outbreak of the war, on publication of «unreliable socially significant information» (for more information, see the chapter «Blocking and civil liberties»). Most of the other justifications listed in the law «On information» can be used both to ban child pornography or drug sales, and for political repression. According to experts, blocking by the decision of the Prosecutor General’s Office (in particular, under Article 15.3 of the Law «On information») is more often a restriction of political freedoms than blocking on other grounds — such as illegal sale of alcohol or documents, information about drugs, publications about suicide, or pornography involving minors. This is how the lawyer and legal analyst of the Agora group, Damir Gainutdinov, describes these mechanisms: «Generally, in all prosecutor’s blockings the resource shutdown comes first, and only then the website owner is notifiedand gets the opportunity to exit the Unified Domain Name Registry and plead for unblocking. That is, prosecutors are engaged in the most socially dangerous and important decisions on blocks. Where we are talking about drugs, suicide, pornography and alike, authorities first notify the owner of the resource, then wait a day until the owner deletes the banned information, and only then put the site in the Registry if it is not deleted. And if the resource is blocked by prosecutors, they immediately put it into the Register and block it, and only after that the owner of the resource is notified. The prosecutors' topics are calls for protests, fake news, and so on.»

The blocking of publications by political opposition institutions (and not individual pages or websites) is usually the result of centralized political decisions. In this case, the bans are not related to the content of specific publications, but to their belonging to an institution that has become a target of political repression — Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), Open Russia, Team 29, Project, etc. Such blocks are always accompanied by other restrictions, up to criminal cases. Galina Arapova (Mass Media Defense Center) gives an example of the understanding of the term «mirror», which is used by Russian courts and the Prosecutor General’s Office: «Law enforcement agencies and courts understand „mirrors“ a little awry, » says Arapova.«It doesn’t matter what content is there, but if a site has a connection with an organization that they want to block, then it is considered a mirror. Even if it is called differently and the content on it is different. This makes it possible to apply quite arbitrarily to new sites the decision that was made earlier on another occasion and for other content.»

Since 2012, the Russian authorities have been creating and developing a legislative framework for the possibility of unlimited blocking — only to the law «On Information, » 84 amendments have been made over the past two years. Simultaneously, the regulators (Roskomnadzor and others) ordered the development of technologies for automated control over the dissemination of information on the Internet. Finally, the mechanisms of blocking (judicial and extrajudicial) were worked out — for individual pages, entire sites and domains; with the possibility of unblocking, «slowing down» and full domain revocation, etc.

If until February 24, 2022, the blocks could take place in different ways — with and without notification, with the ability to delete content and retain access to the resource — then immediately after the outbreak of the war, most of the blocks began to occur immediately and extrajudicially, on the basis of Article 15.3 of the law «On Information».

Internet and censorship

In February 2016, the then head of Roskomnadzor, Alexander Zharov, commented on the frequent accusations of censorship against the agency: «Censorship involves reviewing an article or other information even before it is broadcast or printed. And we react after the fact. Therefore, we do not have any censorship.» According to the Constitution of the Russian Federation, which Zharov also quoted, censorship is prohibited in Russia. The question, however, is how exactly it is defined. The Law «On Mass Media» of 1991 (Article 3) provides the following definition: «… the requirement from the editorial office of a mass media outlet on the part of officials, state bodies, organizations, institutions, or public associations, to pre-coordinate messages and materials (except in cases when the official is the author or the interviewee), as well as the imposition of a ban on the distribution of messages and materials, their individual parts…».

The «requirement… to pre-coordinate messages» refers to the Soviet censorship system and, accordingly, to the traditional press — television, radio and newspapers. This algorithm is technically unrealizable in the case of publications on the Internet: access to it is democratic, and total control of the content of messages before their publication is impossible. However, the second part of the definition from the same article, namely «the imposition of a ban on the distribution of messages and materials, » can be understood as a separate type of censorship, which directly refers to the blocking of Internet resources. In 2010, the Supreme Court issued the plenum resolution «On the practice of application by courts of the Law of the Russian Federation „On Information“, » in which it defined written warnings, as well as the imposition by the court of a ban on the production and release of mass media as «not censorship.» According to the resolution, such bans are «established by federal laws in order to prevent abuse of freedom of the media.» Thus, it can be said that there is systematic censorship in Russia, which is carried out by the authorities and which is not recognized by them as such.

Without calling its own actions «censorship, » the state, nevertheless, uses this term to define the policy of global Internet platforms that restrict access to official Russian channels and accounts. Thus, the word «censorship» appears in the explanatory note to the bill «On Amendments to the Federal Law „On Measures of Influence on Persons Involved in Violations of Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms, the Rights and Freedoms of Citizens of the Russian Federation“» (adopted in December 2020 under the number 481-FZ):

«In fact, since April 2020, the authorized agencies of the Russian Federation have been recording complaints from the editorial offices of the media outlets about the facts of censorship of their accounts by foreign Internet platforms Twitter, Facebook and Youtube. Such media outlets as Russia Today, RIA Novosti, Crimea 24, were censored. In total, about 20 facts of discrimination were recorded.»

This is not really about state censorship, but about the policy of commercial corporations. However, it has a special definition in the law «on censorship»: «… a restriction by the owner of an Internet resource on the dissemination by users of… socially significant information on the territory of the Russian Federation» if it «violates the right of citizens of the Russian Federation to freely seek, receive, transmit, produce and distribute information.» In response to such «censorship» Roskomnadzor blocks foreign Internet sites and social networks.

If in Russia the concept of «censorship» is used only in relation to foreign platforms, then in European and, more broadly, Western judicial practice it occurs in the context of Russian information policy. In the case OOO Flavus and Others v. Russia, in which the ECHR in 2020 decided that the Russian law «On Information» and the practice of blocks violates two articles of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms at once, one of the invited experts in his commentary («third-party intervention») calls widespread blocking of sites «digital censorship.» However, this is rather an exception — in the decisions of the court itself on cases of blocks in Russia, the term «censorship» is not used.

This term is much more common in international human rights practice. For example, Special Rapporteurs on freedom of expression in their declarations label as «pre-censorship» the Internet content filtering systems that are not controlled by end users (p. 88). International human rights NGOs and activists in the field of freedom of speech understand this term even more broadly and actively use it in reports on Russian policy towards the Internet.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, monitoring and reports focused on the routine practice of Roskomnadzor. Thus, the terms «censorship», «online censorship», «Internet censorship», etc. have appeared in Human Rights Watch’s 2017, 2020 and 2021 reports, as well as in Freedom House and Censored Planet reports. In particular, the authors of Censored Planet noted that against the background of the growth of cyber censorship around the world, «including in reportedly „free“ countries, » the Russian example is particularly noteworthy: «A country that once had very little censorship has been thrust into the spotlight due to… their steadily growing blocklist.»

The policy of the Russian authorities towards the Internet contradicts its technological essence. As the authors of the report on the Russian regulation of the Internet by the Censored Planet project note, the distribution and decentralization of networks is no longer a guarantee of the protection of freedom of speech. «It was long thought that large-scale censorship on decentralized networks like Russia, United States, India and the United Kingdom was prohibitively difficult, » they write. «Our exhaustive study of Russia’s censorship infrastructure shows that that is not the case.» In their opinion, «naive» censorship gave way to advanced technologies when Roskomnadzor became able to centrally manage traffic routing thanks to the law «on the sovereign Runet» (see the chapter «The Sovereign Runet»).

Experts of the Roskomsvoboda project disagree with the authors of the report. In fact, at a closed round table on Internet blocks held by OVD-Info on February 8, 2022, the head of Roskomsvoboda, Artem Kozlyuk, expressed a different position from Censored Planet. «The Internet was specially created using such protocols to avoid unnecessary limits and blocks, » Kozlyuk said. «So that each bit reaches the end it is intended for. If there are any restrictions on the path of this bit, it will still try to reach the endpoint. Online censorship contradicts the principle of the Internet. Yes, there will be a struggle of technologies, but banned information will always be distributed — if not through one, then through other channels.»

After February 24, when mass blocking of media outlets, individual posts and accounts of activists and human rights defenders began, and new articles of the Administrative Offense Codes and the Criminal Code were adopted, making it liable offenses to «discredit» and «distribute unreliable information» about the Russian armed forces, many experts and observers began to talk about «military censorship.» In fact, in the latest ranking of freedom of speech, the authors of Reporters Without Borders separately pay attention to the situation in Russia, which has dropped from 150th place to 155th: «In Russia, the government has taken complete control of news and information by establishing extensive wartime censorship, blocking the media, and pursuing non-compliant journalists, forcing many of them into exile.»

The Network Freedoms project has created a map of Russian cities where people were held liable under the new Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses, calling it a «Map of military censorship.» The Roskomsvoboda project also describes the situation, publishing data on the blocks of websites for «fakes» about the Russian army (as of May 5, 2022, there were 3,000 such blocks).

Legislation on Internet blocking

From amendments to the law «On the Protection of Children from Information» to the complete isolation of the Runet

Formal conditions for the start of the Internet resource blocking were created in 2012 by amendments to the law «On the Protection of Children from Information Harmful to their Health and Development» (139-FZ). Then definitions of Internet-related terms («website, » «page, » «domain name, » «network address, » «hosting provider, » «site owner») were introduced into the legislation, " and the Unified Register» and the agency responsible for it, Roskomnadzor, were created. In 2012, the thematic definition of materials, access to which should be blocked by a court decision (Article 15.1, dedicated to the Register), was limited to pornography involving minors, information about ways to commit suicide, as well as about the manufacture or purchase of drugs. However, even then a clause was formulated that did not relate to the protection of children: «information prohibited for dissemination in the Russian Federation on the basis of a court decision that entered into force on the recognition of information as prohibited for dissemination.» That is, information recognized by the court as extremist and included in the Federal List of Extremist Materials.

Although it was about the protection of children, which implied a public consensus, activists and experts expressed concern about the new law, which, in their opinion, could be used to restrict freedom of speech. In addition, together with this law, a number of other laws were passed restricting political freedoms — from a sharp increase in fines for participating in «unauthorized rallies» to the law on «foreign agents.»

Indeed, after a number of amendments, the law 149-FZ «On Information» began to be used to block a wide range of resources. The most radical changes were made at the end of 2013 by the Lugovoi Law (398-FZ). Then Article 15.3 appeared, which introduced extrajudicial blocking for «extremism, » namely, for «information containing calls for mass riots, extremist activities, participation in mass (public) events held in violation of the established procedure…» Thus, a ban on the dissemination of certain types of information that was introduced in order to protect children, gradually turned into a multi-tool for restricting freedoms.

The Lugovoi Law also described the blocking mechanism, which includes a long chain: at the request of the Prosecutor General or his deputies, Roskomnadzor requires the erasure of information from the telecom operator and notifies the hosting provider; the operator restricts access to the resource, and the hosting provider informs the owner of the resource about the requirement to delete information; after the information is deleted and Roskomnadzor is notified about it, the agency allows the telecom operator to unblock the resource. At the same time, there was no clear indication in the law what exactly is being blocked — a page, domain or IP. As a result, other resources that are thematically unrelated to the object of the ban and belong to other people were often blocked by domain and IP.

Employees of organizations and site owners either did not receive any notifications at all, or received letters from Roskomnadzor, which did not specify which information published on the site contradicts the law. Moreover, such a norm was originally laid down in the Lugovoi Law, according to which the Prosecutor General is not obliged to inform the owners about the reasons for which their sites were blocked.

According to the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, among the first fifteen resources blocked under the Lugovoi Law in 2014, together with the Islamist sites (Hunafa.info, VDagestan.com, Daymohk), there were online publications Yezhednevnyy Zhurnal, Kasparov.ru and Grani.ru, several websites with news about the march for the federalization of Siberia, the article «The Appeal of Right Sector to the peoples of Russia, » as well as the blog of Alexei Navalny and its 28 mirrors.

By 2021, Lugovoi Law had become the main legislative instrument of censorship: for example, the wording «calls for mass riots, extremist activities» from Article 15.3 allowed the blocking by the decision of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the sites of the «Team 29», several sites supported by Mikhail Khodorkovsky («Open Media», «MBH Media», «Pravozashita Otkrytki, » duma.vote), as well as dozens of sites related to the activities of Alexey Navalny (Lyubov Sobol’s and Navalny LIVE channel, Georgy Alburov’s, Leonid Volkov’s and Vladimir Milov’s, even earlier, in 2018 — navalny.com).

In 2017, the law on «Mass Media-foreign agents» (327-FZ) amended the law «On Mass Media» — the concept of «foreign mass media performing the functions of a foreign agent» appeared in Article 6. The same law also made further amendments to the law «On Information»: the list of grounds for extrajudicial blockages (Article 15.3) was supplemented with the wording «information materials of a foreign or international non-governmental organization whose activities are recognized as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation» (the law on «undesirable organizations» (129-FZ) was adopted two years earlier, in 2015). Under this pretext — the materials of an «undesirable organization» — in 2021, the pages with investigations of the «Project» and «Open Media» were blocked. In addition, the following wording also appeared in Article 15.3: «information allowing access to the specified information or materials.» What kind of information, the law did not specify, and experts interpreted it as ordinary hyperlinks. In the expert opinion of the Human Rights Council on the law on «Media-foreign agents», the director of the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, Alexander Verkhovsky, noted that such wording could lead to mass blocking of any pages, websites, as well as blogs and social networks. Media outlets, bloggers and ordinary users of social networks for many years published links to the materials of organizations that were not considered «undesirable» at that time. «Thus, » Verkhovsky writes, «the introduction of this rule means giving the Prosecutor General’s Office an almost unlimited opportunity to block access to a huge number, possibly to the majority, of websites and blogs, at least of socio-political subjects. But such powers of extrajudicial sanctions cannot in any way be considered proportional to the issues that, according to the explanatory note, the bill is intended to solve.»

In the same year, 2017, but a few months earlier, other amendments to the law «On Information» (276-FZ) were adopted, introducing Article 15.8. It described «measures aimed at countering the use of information and telecommunication networks and information resources on the territory of the Russian Federation, through which access is provided to information resources and information and telecommunication networks, access to which is restricted on the territory of the Russian Federation.» Both the press and Roskomnadzor perceived this as a ban on the use of VPNs and anonymizers to bypass blocks. Shortly after the publication of the law, Roskomnadzor demanded from companies that provide the possibility of using VPNs and anonymizers to register in the FGIS system, which provides access to the register of prohibited Internet resources. This allows one to track whether anonymizers add addresses of blocked sites to the blacklist.

Almost 10 years of legislative activity were spent on amendments to the law «On Information», which continued to expand the list of prohibited types of information, describe and codify those responsible for its publication and blocking, and also toughened penalties for violating the law:

- In 2018, Law 472-FZ introduced another «children’s» clause into Article 15.1 (on the register) — on «inciting minors to commit illegal actions.» In 2021, this wording allowed the Investigative Committee to open a criminal case against Leonid Volkov for calling for participation in «unauthorized» rallies in support of Alexei Navalny.

- On March 18, 2019, the law 30-FZ was adopted, amending the law «On Information». The new article 15.1.1 is called «The procedure for restricting access to information expressing in an indecent form, that offends human dignity and public morality, obvious disrespect for society, the state, official state symbols of the Russian Federation, the Constitution of the Russian Federation, or bodies exercising state power in the Russian Federation.» In fact, this has become an extension of the scope of the «Lugovoi Law», since the mechanism for blocking websites, pages and blogs under this article does not differ from the mechanism for blocking «extremist» materials: access restriction occurs at the request of the Prosecutor General or their deputies, and Roskomnadzor is responsible for it. The Mass Media Defence Center notes that this wording is extremely vague and does not give an understanding of what exactly can be considered an «indecent form, » as well as what exactly is meant by «bodies exercising state power.» For example, in the 2019 case of insulting the governor of the Arkhangelsk Region, the Supreme Court clarified that «the president, the Federal Assembly (the State Duma and the Federation Council), the government and the courts are considered to be [such] bodies. In the regions, local authorities — assemblies of deputies and governments — are added to them.» That is, governors do not belong to this list — however, courts in their practice often include the police and the FSB in the concept of «bodies exercising state power.»

- On the same day, Law 31-FZ was adopted, which introduced the concept of «unreliable socially significant information, » the dissemination of which is also punished by extrajudicial blocking (under Article 15.3). Moreover, this wording applies only to online publications, which do not include, for example, «news aggregators» and traditional media, but include the sites of these media, as well as sites registered as online publications. In this case, the materials are blocked according to a special algorithm: the Prosecutor General informs Roskomnadzor, the latter informs the editorial office of the online publication, and the telecom operator appears in the chain only if the editorial office has not deleted the material and it needs to be blocked. Both the press and the legislators themselves called this law the «Fake News Law.» At the same time, amendments were made to the Administrative Offense Codes (part 9 of Article 13.15), which introduced fines for publishing «unreliable socially significant information» (the penalties were tightened next year). After February 24, this law, with subsequent amendments to the Administrative Offense Codes and the Criminal Code, became the main instrument of military censorship.

According to Damir Gainutdinov, the law on «fakes» was in practice not used until 2020 — then it began to be massively applied against resources publishing «false information» about the coronavirus: «During this time, practice has developed, explanations of the Supreme Court have appeared on how to apply it, and now on this basis it is applied to information about the war.» A signature case is the blocking of the resource «Taiga.info» two weeks before the start of the war: the site published an article about food shortages in the village of Khatanga on Taimyr, after which this text was blocked on the grounds of violating the article on «fakes.» The Agora group managed to appeal this blocking, but two weeks later the website «Taiga.info» was blocked completely — with the same justification, but this time for covering the war.

- In the same 2019, Law 426-FZ introduced the requirement of mandatory labeling of «foreign agents, » the absence of which may also be punished by blocking of the resource (Article 15.8).

- In 2020, four new laws were adopted, which introduced 64 amendments to the law «On Information, » but most of these edits were devoted to financial security (FZ 479), information on the illegal sale of medicines (FZ 105), and other topics not directly related to political rights. In December of the same year, the «law on censorship» (482-FZ) was adopted, which allowed Roskomnadzor to block or slow down Internet platforms if they restrict the dissemination of «socially significant information.»

The last changes in the substantive part of the law (that is, in the enumeration of the types of information, the publication of which may lead to a block) were made already in 2021:

- Law 43-FZ introduced a new article 15.3-1, according to which websites with election campaigning and other election information may be subject to extrajudicial blocking if the content contradicts the law. In this case, the election commission has the right to initiate blocking by making a request to Roskomnadzor, which, in its turn, makes a request to a telecom operator. That is, the site is blocked at first, and only afterwards its owner can delete the information and request unblocking.

- Law 260-FZ for 2021 introduced a new article 15.1-2: «The procedure for restricting access to false information that discredits the honor and dignity of a citizen (individual) or undermines their reputation and is associated with the accusation of a citizen (individual) of committing a crime.» The article describes the mechanism: a citizen who finds false information about themselves writes a plea addressed to the prosecutor, after which the prosecutor’s office checks the information for authenticity and, in case of violation, sends a notification to Roskomnadzor, which notifies the hosting provider, and the provider, in turn, notifies the site owner. If the information is not deleted by the owner within a day, the site is blocked by the telecom operator.

- Law 288-FZ, adopted on the same day as the previous one (260-FZ), added to Article 15.1 (on the register) another type of information for which a website or page is blocked: confidential information about judges, officials, and law enforcement agencies.

- Law 250-FZ added to Article 15.3 (on extrajudicial blocking) a clause on the resources of financial fraudsters — such as imitation of official bank websites, as well as sites that «encourage participation in financial pyramids.» In this case, the blocking may occur at the initiative of the Bank of Russia.

- In December 2021, Law 441-FZ was adopted, which expanded the grounds for extrajudicial blocks (Article 15.3) by introducing four new points: from that moment on, not only «calls for mass riots and the carrying of extremist activities» were banned, but also «justification and (or) rationale for the carrying of extremist activities, including terrorist activities»; «false reports of acts of terrorism»; materials of organizations recognized as terrorist or extremist and links to them; as well as «an offer to purchase a forged document granting rights or releasing from obligations.»

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the state information policy sharply tightened. However, most of the legislative tools for quickly blocking unwanted publications had already been created by this time, so between February 24 and May 28, mainly those bills were submitted to the State Duma and adopted that clarified the wordings and introduced new penalties for publications — fines and prison terms.

So, on March 4, 2022, laws 31 FZ and 32 FZ were adopted, which added to the Administrative Offense Code and the Criminal Code articles on «discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, » «calls for the introduction of restrictive measures against the Russian Federation» (that is, sanctions), as well as on «public dissemination of deliberately false information about the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation» (Articles 20.3.3 and 20.3.4 of the Code of Administrative offenses; Articles 280.3 and 284.2 of the Criminal Code). On March 22, 2022, amendments were made to these articles, which added to the list of illegal actions «discreditation» and «dissemination of false information about the work of Russian state bodies abroad.» If the «public dissemination of deliberately false information» about the use of the Russian army or about the actions of state bodies abroad entailed «grave consequences, » then the punishment can be up to 15 years in prison — this is the toughest of the laws adopted after February 24, 2022. In practice, this led to the fact that individual authors and entire editorial offices deleted their publications themselves or announced a complete refusal to cover military operations.

On April 6, a bill on the extrajudicial termination of the work of media outlets by the decision of the Prosecutor General’s Office was introduced in the State Duma, giving the Prosecutor General’s Office the right to close Russian media outlets without judicial intervention and initiate a ban on foreign media working in Russia. The initiators of the bill called these measures «mirroring, » referring to the blocking of official Russian media on foreign platforms (Youtube, Facebook, etc.) that have become more frequent after the outbreak of the war. At the time of writing, this bill has been approved in the first reading.

According to the bill, the Prosecutor General’s Office will be able to declare the registration of any media invalid if it is found to:

- spread «fakes» or information that «offends human dignity and public morality»;

- «express obvious disrespect for society, the state, official state symbols of the Russian Federation, the Constitution, state authorities»;

- disseminate information containing «calls to participate in unauthorized public events» or to impose sanctions;

- contain propaganda, justification or defence of «extremist activity».

In this case, the activities of the media outlet will be banned, and employees will lose their accreditation.

Moreover, this bill provides for the extrajudicial blocking of websites containing «false information disseminated under the guise of reliable reports» about the use of the armed forces, the activities of government agencies abroad, as well as their discreditation or calls for sanctions. After the adoption of the new amendments, the Prosecutor General’s Office, with the «repeated dissemination of such information, » will have the right to send a request to Roskomnadzor for the immediate blocking of the site, as well as resources «confusingly similar to it.»

On April 25, a bill «On control over the activities of persons under foreign influence, » or rather, amendments to the legislation on «foreign agents, » was introduced to the State Duma. This draft law provides for the possibility of extrajudicial blocking of an information resource of a «foreign agent» in case of violation of the legislation on «foreign agents» (for example, for lack of labeling). The law also expanded the definition of this term, and hence the grounds on which Roskomnadzor can block the website of a person or organization recognized as a «foreign agent.» From this moment on, any person or structure (except for public authorities, state-owned companies and state corporations) can be considered a «foreign agent» if they not only receive foreign funding, but also are «under foreign influence» — with the widest possibilities for interpreting this definition. The first reading of the bill is scheduled for June 2022.

Who is punished

In 2012, when the first law on blocking was adopted, the main actors of the Internet were considered to be «hosting provider, » «site owner, » as well as «telecom operator» (the latter term was taken from the law «On Communications»: in Article 46 «Responsibilities of telecom operators» the Internet has been added to the traditional radio, telephone and television).

Organizers of information dissemination

- In 2014, the term «organizer of information dissemination» was introduced (97 FZ, Article 10.1). According to the law, it is.».an entity carrying out activities to ensure the functioning of information systems and (or) programs for electronic computers that are intended and (or) used for receiving, transmitting, delivering and (or) processing electronic messages of Internet users.» That is, an «organizer of information dissemination» is a website, platform, service or application that allows users to exchange messages or publish their own content.

According to the law, the «organizer» is obliged, firstly, to enter themselves in the appropriate register; secondly, to store information about the exchange of messages between users and information about users themselves for six months (this information should be stored only on the territory of the Russian Federation); thirdly, to provide this information to security and investigative agencies and keep the secret of the activities of these bodies.

- In 2016, the obligation to store the messages themselves was added to this list, as well as to provide the security and investigative agencies with means of decoding messages (374 FZ). The history of blocking of the Telegram app began with this point: Pavel Durov unsuccessfully tried to explain to the «authorities» that Telegram does not have access to encryption keys.

Hundreds of services and platforms that allow users to exchange messages and emails, publish their own information or even just comments, are in the register of «organizers of information dissemination, » which is maintained by Roskomnadzor. These can be both mail services and interactive maps, dating services, news sites, social networks, as well as any sites and applications if they allow the user to participate in the creation of content. In February 2022, the first 15 items of the register included the following «organizers of information dissemination»: several services of Yandex, Rambler and Mail.ru, Odnoklassniki, VKontakte, ICQ, Habrahabr, the dating site mamba.ru, a news site with a comment feature «Roem», km.ru, www.liveinternet.ru, wikimapia.org, medianetworks.ru, a website about fire safety www.0-1.ru, the website «Moscow Tatar Free Word», etc. If the «organizer» refuses to enter the resource in the registry, access to it is restricted — it is blocked.

In April 2018, Article 10.1 became the reason for which the Zello app was blocked. It isa voice messenger that allows you to create thematic groups and which was used by truckers during protests against the introduction of the «Plato System» (a system for charging cars with a maximum permissible weight of over 12 tons). At the time of blocking, there were more than 14 thousand subscribers in the «Truckers» group (and in total about 400 thousand people used Zello in Russia, of which, according to RBC, about 100 thousand were in the «Debate» group, where they discussed politics and economics, and about the same number were in the «Religion and Politics» group). Roskomnadzor sent a request to Zello to register as an «organizer of information dissemination» within three days, threatening to block it. Inclusion in the registry automatically led to another requirement — according to the «Yarovaya Law», the «organizer of information dissemination» must store user data for a year and provide them at the request of law enforcement agencies along with encryption keys. However, voice messages are transmitted by Zello in real time and are not stored on the server for a long time. Zello developer Alexey Gavrilov (the company is registered and operates in Austin, Texas) commented on this requirement as follows: «We would have signed up for the registry, but we can’t store information about users in Russia… We only have 10% of users from Russia, and now we have to store everyone’s data? This is nonsense.»

The app was blocked, however, during 2017 and the spring of 2018, truckers continued to use Zello due to the block bypass technologies built into it in 2014. Then Roskomnadzor blocked the servers that were used by the app. Among the 36 blocked servers, 26 were owned by Amazon, which asked Zello to stop using its servers to bypass the blocks. The developers agreed, but a few months later Roskomnadzor discovered that Zello was now using Google’s servers and blocked them. In a letter to the operators, as Meduza writes, Roskomnadzor reported that blocking subnets (in particular, Google servers) was an «experiment.» Such «experiments» took place for several years and were the result of the activities of a special department created by Roskomnadzor in 2017 to develop technologies for blocking prohibited Internet resources.

Search engine, news aggregator, owner of an audio-visual service, owner of a social network

- In 2015, the concepts of «search engine» and «search engine operator» (264 FZ) are introduced. Among other duties, the operator must, at the request of any citizen, remove access to «false information» (the so-called «right to be forgotten»).

- In 2016, the law introduced the concept of «news aggregator» (208 FZ). This is a Russian legal entity or a citizen of the Russian Federation who are «owners of a computer program, owners of a website and (or) a website page on the Internet» with the following conditions: these sites or pages publish information in Russian or the national languages of the Russian Federation and they have at least 1 million views per day. Like the «organizer of information dissemination, » the «news aggregator» is obliged to enter themselves in the appropriate register and store information about users for 6 months.

- In 2017, the law introduces the concept of «owner of an audiovisual service» (87 FZ) — a website, application, etc., which provides access to content «for a fee and (or) subject to viewing advertising aimed at attracting the attention of consumers located on the territory of the Russian Federation.» To have the right to distribute audiovisual content, the owner of the service must have an audience of more than 100 thousand users per day, talking only about those who are located on the territory of the Russian Federation. The owners of the audiovisual services also have their own registry and their responsibilities also include storing information about users for six months.

- Finally, in 2020, in addition to dozens of other amendments, the law «On Information» introduces the concept of «owner of a social network» (530 FZ). This is the owner of a website with 500 thousand or more users per day located on the territory of the Russian Federation. The «owners of social networks» also have their own registry and responsibilities, including not only storing information about users and their messages, but also compiling annual reports, and constantly monitoring the content of social networks.

- According to the draft law of 2022 «On control over the activities of persons under foreign influence, » information resources of «foreign agents» can also be blocked regardless of their type (website, social media account, etc.).

Defining state borders on the Internet

The explanatory note to the bill on the «sovereign Runet» begins with a mention of «the aggressive nature of the US National Cybersecurity Strategy adopted in September 2018.»

According to the explanatory note, the objectives of the new law are:

- «minimizing the transfer abroad of data exchanged between Russian users»;

- «control over cross-border communication lines and traffic exchange points»;

- introduction of a system of «centralized traffic management.»

To do this, the law provides for the installation of technical means which will make possible to restrict access to resources with banned information not only by network addresses, but also by prohibiting the passage of passing traffic. We are talking about communication lines that cross the state border of the Russian Federation: in these places, telecom operators are required to install «technical means of countering threats» (TMCT). Further orders and other documents clarify that we are talking about software for deep content filtering. According to the Roskomnadzor report for 2020, TMCT are installed on 100% of mobile devices and 50% of stationary ones.

The Law 90-FZ also introduced a new Article 14.2 of the law «On Information», which presupposes the creation of a «national domain name system.» The Roskomnadzor order issued a few months later identified the domain names included in the national system:

- domain names included in the top-level domain.RU;

- domain names included in the top-level domain.РФ;

- domain names included in the top-level domain.SU;

- domain names included in the top-level domain managed by a Russian legal entity.

In fact, we are talking about the nationalization of those Internet domain zones that have traditionally been Russian-speaking, although they were not under the direct control of the Russian Federation. The press wrote about the threat of full state control over the Coordination Center of National Domains back in 2016. Then, according to the journalists of the newspaper Kommersant, at a meeting in the Ministry of Communications with the participation of representatives of the FSB, the Ministry of Finance, the Federal Tax Service and Roskomnadzor, it was proposed «to de facto eliminate» the CC «in favor of the design formulated in the so-called bill on the «autonomous system of the Russian Internet.» That is, the actions of the Russian authorities in relation to the Internet have been logical and consistent, at least since 2016, given that the goal was isolation and control over the network.

The Sovereign Runet

Vladimir Putin clearly stated for the first time that the Internet is «dangerous» for Russian society and needs state control in April 2014, during a media forum in St. Petersburg. According to the president, «the Internet emerged as a special project of the US CIA, and is developing in the same vein»; the press of that period wrote about the plans of the Russian authorities to strengthen the country’s information security. In particular, regarding the placement of servers of large national Internet resources on the territory of Russia — this measure was presented as necessary, since «the Americans control the information flows» passing through their servers.

A couple of months before the media forum, the issue of control over the Internet was actively discussed in the State Duma and in the press: in February, amendments were made to the law «On Information» (adopted in April 2014 under the number 97 FZ), which equated bloggers with the media and obliged owners of Internet resources to store on the territory of Russia for six months information about users and the exchange of messages between them, as well as provide this information to security and investigative agencies. The accompanying amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses provided for fines of up to 200 thousand rubles (for legal entities) for non-compliance with the requirements of this law. Large Russian IT companies, such as, for example, Mail.Ru Group, as well as human rights activists and experts criticized the new bill. The former pointed out that the implementation of the project would entail large financial losses, the latter claimed that the law could easily turn into an instrument of censorship.

One of the initiators of the bill, MP Irina Yarovaya, commented on it as follows:

«The organizers of the dissemination of information… will store information about the facts of the connection, but not the messages themselves. It is important to emphasize that bloggers are not required to store such information, since it is the prerogative of those who ensure the functioning of the information system or program. Thus, the norms of international law are not violated.» Law 97-FZ became part of the so-called «anti-terrorist package, » which also included laws expanding the powers of the FSB in the fight against terrorist threats and limiting non-personalized payments. Commenting on his initiative, Andrei Lugovoy mentioned the «events in Ukraine, » during which, according to him, «all sorts of Western transfers for a penny inside the country merged into a multimillion-dollar stream of support for extremism and fired on the Maidan.»

The following «anti-terrorist» laws, also initiated by Yarovaya in 2016, increased the storage period of information to one year and obliged site owners to store, in addition to information about the fact of messaging, also the content of these messages.

Thus, 2014 was the beginning of a large campaign to create a system of total control over the Russian segment of the Internet. To do this, the Russian authorities needed to develop ways to isolate this segment from the global Internet, which they understand as predominantly American. Three framework documents — the «Information Security Doctrine» (2016), the «Strategy for Countering Extremism» (2020) and the «National Security Strategy of Russia» (2021) — in combination with the laws «on the sovereign Runet» (2019) and «on landing» (2021) have created a legal basis for isolating the Russian segment of the network.

- «The Information Security Doctrine» appeared in December 2016 (the previous one was published in 2000). The main threats mentioned in it were: foreign intelligence services and the military; the technological lagging of the Russian Federation; terrorists; fraudsters; as well as two points that were not in the previous version of 2000 — discrimination of the Russian media in the West and «extremism.» Technically, the main danger, according to the doctrine, is the cross-border circulation of information — between users located on the territory of Russia and outside it.

- In «Strategy for Countering Extremism» (2020), the dissemination of information on the Internet, for example, calls for «unauthorized» rallies, is listed among the «most dangerous manifestations of extremism.»

- In «The National Security Strategy of Russia» (2021), special attention was paid to the issues of information security and the main factors threatening this security. According to the strategy, the Internet is an instrument of «interference in the internal affairs of the state» by foreign intelligence services, as well as control over information resources by transnational corporations. On the one hand, these corporations and states, «destructive forces abroad and within the country, » are engaged in «censorship and blocking of alternative Internet platforms, » that is, Russian media abroad. On the other hand, they «impose a distorted view of historical facts» and encroach on the foundations of the constitutional system of the Russian Federation, human and civil rights and freedoms, including by inspiring «color revolutions.»

The head of the Roskomsvoboda project, Artem Kozlyuk, in an interview for Novaya Gazeta, stressed that the «National Security Strategy of Russia» is an extension of the law «on the sovereign Runet»: «So, the aggressive points of this strategy are not surprising and generally fall into the trend of the state towards aggression towards the Internet space and communications. Our state focuses its attention on the Internet not as an instrument of progress, creation, information exchange, but as an instrument of propaganda, politicization, dissemination of Western influence, etc.»

The above-mentioned framework documents developed the concept of isolation of the Russian segment of the Internet — and at the same time new legislative initiatives introduced regular amendments to the laws «On Information», «On Communications», the Criminal Code and the Code of Administrative Offenses. In fact, in 2019, the law on the «sovereign Runet» (90-FZ) was adopted, in which the idea of American control over the Internet was reworked into the concept of the «sovereign Runet» — an isolated information system with special control over cross-border communication lines. And in 2021, the law «on landing» (236-FZ), or «On the activities of foreign persons in the Internet information and telecommunications network on the territory of the Russian Federation» was adopted, according to which all large foreign companies must open their offices in Russia under threat of blocking.

IT giants

Throughout 2020, the Government of the Russian Federation, Roskomnadzor, the Ministry of Digital Development and other agencies have been developing rules and technologies for isolating the Russian segment of the Internet in accordance with Law 90-FZ. According to the experts of the Net Freedoms Project, «in 2020, regulatory support for the isolation of the Runet was generally completed, » since the government approved the rules for «centralized network management» and the regulations for the installation of TMCT (technical means of countering threats), and Roskomnadzor began to introduce them into the industry. Net Freedoms Project separately noted that «threats, in particular, include not only [the likelihood of] violation of confidentiality and integrity of communications, but also the possibility of access to information or resources prohibited in the country.» That is, the law formally adopted to create a stable system in case of «disconnecting Russia from the Internet» led to the development of a system for controlling or banning information, including blocking websites.

All this time, experts, activists and journalists wondered how the Russian authorities were going to influence the IT giants — Google, Facebook, Twitter, and other corporations whose owners and management were difficult to convince to follow Russian laws. In mid-2021, to solve this problem, the law «On the activities of foreign persons in the Internet information and telecommunications network on the territory of the Russian Federation» was adopted. The initiator of the law, Member of Parliament Alexander Khinshtein, calls it «the law on landing, » and experts of the Roskomsvoboda project — «the law on hostages.» The bottom line is that large foreign Internet corporations are obligated to open representative offices on the territory of the Russian Federation, which will be held liable before the Russian state — including for limiting the dissemination of banned information.

The law defines Internet corporations subject to new regulation as companies that:

- were founded abroad by citizens of other countries;

- have at least 500 thousand users from Russia;

- distribute information in Russian or the official languages of Russian Federation subjects;

- distribute Russian-oriented advertising;

- process information about users from Russia;

- receive money from Russian citizens and legal entities.

The law stipulates the following measures of coercion in case of refusal of these companies to open a representative office in the Russian Federation:

- informing Russian users about violations of the law;

- prohibition on the transfer of Russian money to a foreign entity;

- a ban on the cross-border transfer of personal data of Russian users (Russians and Russian organizations will not have the right to transfer such data, so, in fact, it is a partial block);

- complete blocking on the territory of Russia.

In 2021 alone, foreign IT giants received fines of more than 9.4 billion rubles for refusing to delete content and localize user data. Experts of the Net Freedoms Project in the report on the state of Internet freedom for 2021 (according to data for the first 9 months) listed foreign Internet companies that already got into the Unified Register: Youtube, Facebook, WhatsApp, Zoom, Telegram, Viber, Spotify, TikTok, Twitch, Pinterest, as well as Apple. «This means, » the report says, «that each of the services is legally one step away from being slowed down or blocked, as happened with Twitter. Installation of Runet isolation equipment on communication networks (TMCT) already allows it.»

Roskomnadzor blocks especially often content related to major opposition movements or organizations. For example, in January 2021, 12 materials on Youtube were blocked, «containing the same video with calls to participate in unauthorized rallies in January 2021.» Google LLC sued Roskomnadzor because there were no references to specific materials at all in the request of the Deputy Prosecutor General, but a video published in TikTok was mentioned. The Arbitration Court of Moscow dismissed the claim of Google LLC, ruling that the measures of Roskomnadzor were «prophylactic and preventive in nature.» In general, IT giants are trying to follow the new legislation — they meet with the Commission to investigate the facts of foreign interference in the internal affairs of Russia, pay fines, promise to remove banned information and apps (for example, in September 2021, Apple and Google LLC removed the Navalny app from their stores, and Google LLC also removed «smart voting» from the browser search results). In addition, Google LLC responds to requests from different states for the removal of certain materials and publishes data on these requests. In 2021, Russia was in first place in terms of the number of such requests (Turkey was in second place, followed by India and the USA). And according to the data for the period from 2002 to 2021, it is clearly visible how the appetites of the Russian authorities grew — especially in the column «Criticism of the government».

On the other hand, Roskomnadzor controls the availability of official (and close to official) channels. The above-mentioned «censorship law» of 2020 was introduced to the State Duma the day after the Youtube channel «Solovyov LIVE» stopped appearing in the ‘trends’ section. Roskomnadzor accused Google LLC of «restricting the distribution of materials by a popular Russian author, preventing the growth of his audience.» In addition, Roskomnadzor sent a request to Google LLC about the reasons for the removal of Vladimir Putin’s address from the NTV Youtube channel, a request to Twitter about the reasons for the absence of the RIA Novosti account in the search results, as well as general requests to several platforms at once, such as «stop censorship of Russian media» (RIA Novosti, RT, Sputnik and «Russia-1»). «In the end, » as the authors of the report «Internet Freedom 2020: the second wave of repression» (the Network Freedoms project) write, «Roskomnadzor announced that it was a «purposeful policy by foreign platforms to influence Russians' access to objective information, » and recommended «Russian media and information resources to maintain the possibility of reliable and quick access to content by posting video materials on the platforms of Russian Internet companies.» Simultaneously, Roskomnadzor initiated an administrative offense case against Google LLC and fined the company for 3 million rubles (this was the third fine).

After February 24, 2022, the situation for most IT giants has changed. Meta corporation has been declared extremist, and social networks Instagram and Facebook belonging to it have been blocked in Russia. Google and Youtube are still available, but they regularly receive threats from Roskomnadzor and from Member of Parliament who initiate most of the bills related to blocking.

How blocks work

Banned information gets into the Unified Register in different ways. The blocking of sites associated with «undesirable organizations» occurs manually and is associated with other methods of repression aimed at the opposition or the media; that is, sites, pages and accounts of individual activists may be blocked not for content, but as a repressive measure. «Some face administrative and criminal prosecution for the fact that they are actually activists, especially in regions where an investigator, prosecutor or employee of the Centre for Combating Extremism decided that they are too loud and it’s time to charge them with something,» said head of the Roskomsvoboda project Artem Kozlyuk at the OVD-Info round table.

In addition, according to the observations of Roskomsvoboda, many departments have a reporting system for the number of blocked resources. «It makes sense to consider each category of banned information separately, » says Kozlyuk. «We have a dozen departments responsible for different pieces of censorship on the web, and they may have their own „ticking system“ arranged differently. The tax service is now in the first place in terms of the number of blocks. This means that they may have a KPI for the number of resources blocked per month.»

There are government agencies that respond to requests for blocking from users themselves, but, according to Roskomsvoboda, «pseudo-public organizations like the League for Safe Internet, cyber vigilantes, cyber Cossacks, cyber guards, » etc. are most often engaged in this. Moreover, a motivation system may exist within these organizations, for example, a «board of honor» with information about the number of complaints sent and the number of resources banned due to them —one, according to Kozlyuk, exists at the «Media Guard» (the project of the «Young Guard of United Russia»).

District prosecutor’s offices, which report on the number of blocked materials, also have some kind of specialization. This new trend was noticed by legal analyst and head of the NetFreedoms Project Damir Gainutdinov: «One district prosecutor’s office specializes in electric fishing rods and illegal fishing gear, someone specializes in devices that help deceive electric meters, and someone — in the sale of alcohol.» According to Gainutdinov, sometimes agencies overlap on topics — as in the case of online alcohol sales, where Rosalkogolregulirovanie (The Federal Service for Alcohol Market Regulation) competes with district prosecutors.

He also notes that in 2021, for the first time, the police initiated some of the blocks. We are talking about sites blocked in connection with cases of administrative offenses. «Previously, everything was limited to the fact that a person was held liable, and now the Ministry of Internal Affairs also requests to block materials, » Gainutdinov says.«And prosecutors now report in their press releases: a person has been brought to criminal responsibility, and materials have been deleted or blocked.»

In May 2022, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there were much more blocks with obvious political justification. Damir Gainutdinov adds: «Now I have a feeling that there is nothing but war… For example, there have been no non-war-related calls to our hotline in recent months. Previously, a dozen a week, at least: prohibited symbols, extremist materials, etc.» Despite this, according to his observations, «departmental blockages» continue, usually not directly related to political statements — for example, sites specializing in the illegal sale of alcohol or documents.

Finally, a noticeable (although small in percentage terms) number of blocks is the result of a direct political decision of the authorities. In such cases, all existing legislative norms are often used at once. Experts conditionally divide the blocks into ‘mass’ and ‘targeted’. The first ones are rather «daily functioning» and are similar to «ordinary house cleaning» for the state, they have already become routine work and occur automatically. «And there are, of course, politically motivated decisions, » says Damir Gainutdinov, «which are taken on the highest levels in relation to certain subjects, be they media or activists.» Such blocks are separate cases, the result of the «order from above.» «Then all laws are applied at once, » explains the director and leading lawyer of the Mass Media Defence Center Galina Arapova. «The organization is recognized as „undesirable“ or „foreign agent“ and all its content is cut out. The most striking example is the blocking of investigations of the „Project“, „Team 29“, FBK. They can be seen as exceptional, and they are clearly political in nature. Here, the whole complex of legislation was adjusted to a specific client, which allowed burning everything down to the ground.»

Alexey Navalny’s projects

In Russia, the largest number of blocks for various reasons, apparently, is connected to portals and publications related to Alexei Navalny and his projects. Over the years, his LiveJournal, investigations, videos on YouTube channels, the Smart Voting project, etc. have been blocked. At the moment, in Russia access is blocked to the site navalny.com, the page of the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), to all the sites of Navalny’s regional offices, and the pages of some of the politician’s associates.

LiveJournal: court decision, calls to participate in protests. Blocking the entire blog instead of individual pages

The first time the politician’s team faced blocks was in 2014: Roskomnadzor blocked Navalny’s personal page in Livejournal. The opposition politician’s blog was included in the unified register of banned information at the request of the Prosecutor General’s Office. The formal reason was that Navalny was then under house arrest as part of the investigation into the Yves Rocher case. It was impossible for a politician to use the Internet, but blog posts continued to appear — the texts were written on his behalf by Navalny’s wife or his associates. «The functioning of this Internet page violates the provisions of the court decision on the election of a preventive measure to a citizen against whom a criminal case has been initiated, » Roskomnadzor said at the time.

However, it is not by chance that the first major blocks of portals related to the coverage of political events began in the same period: the sites of Grani.ru, Kasparov.ru and «Yezhednevnyy Zhurnal» were included in the Unified Register. At the same time, a copy of Navalny’s blog, which was published on Echo of Moscow, was blocked — and the entire website of the radio station was unavailable for some time.

A few weeks later, the Prosecutor General’s Office expressed its position, explaining the blocking of Navalny’s blog differently — not by violating a court decision, but by calling for citizens to participate in «unauthorized mass events.» According to the law on information protection, the first ground — violation of a court decision — does not allow sites to be included in the register of banned information, while «calls» allow this to be done. Probably, the new public position of the Prosecutor General’s Office was connected with this circumstance.

The agency explained that the «calls» appeared in an open group on VKontakte, which was called «The War against Corruption — support for Alexei Navalny.» From the photos and video materials posted in the group, it was allegedly «seen that during the events held, there was resistance to the legitimate demands of police officers.» The materials in the politician’s blog, according to the Prosecutor General’s Office, had a «single thematic focus» with such calls and formed «an opinion on the acceptability of the above actions.»

The group «War against Corruption — support for Alexei Navalny» was demanded to be blocked by United Russia’s Alexander Sidyakin, and on March 13, the day Navalny’s page was blocked in LJ, he received a response from the Prosecutor General’s Office that this request would be satisfied. However, at the time of the release of the department’s statement (April 2), the VKontakte group continued to open, but Navalny’s blog did not.

A few months later, on July 28, the Moscow City Court rejected Navalny’s complaint about the blocking. The court heard explanations of publications in connections with which the blog was blocked. Two entries were given as reasons: the first was dedicated to the events in Ukraine, but contained a call to come to support the defendants in the Bolotnaya Square case, and in the second readers were invited to come to court, where the verdict was to be announced in the same case.

Answering the question about the expediency of blocking the entire blog due to two entries, the Prosecutor General’s Office stated that the law does not oblige it to specify particular blog pages when making a decision on blocking. Roskomnadzor also explained that technically the blocking was carried out by the administration of LiveJournal, and they might not have been able to close access to individual blog entries.

Navalny deleted two specific entries that the Prosecutor General’s Office referred to, but his blog in LiveJournal was unblocked only after a year and a half. According to the opposition politician, he did not understand why the block was not lifted, so at some point he decided to simply delete all the existing entries. After that, on November 11, 2015, the blog was unblocked, and the politician began to fill it in again. Simultaneously, Navalny’s blog appeared on a new domain: navalny.com.

2018: blocks amid elections

The next round of pressure on Navalny and his team with the help of blocking occurred in 2018 and 2019, and, apparently, could be associated with the vigorous activity of the politician in connection with the presidential elections.

To understand the context of the blocks of these years, it is important to take into account that in 2016, Navalny announced his intention to participate in the presidential elections of 2018, after which he conducted a large-scale election campaign during 2017, which was accompanied by regular administrative arrests of a politician (or, for example, attacks by pro-government groups) and some of his associates. In the same year, mass protests «He Is Not Dimon to You» took place in Russia. However, at the end of 2017, the Central Election Commission refused to register Navalny as a candidate for the elections due to an outstanding criminal record in the Kirovles case. In response, the opposition politician launched a campaign calling for a boycott of the elections.

On February 15, 2018, after another rally organized by Navalny, the «Strike of Voters», at which he was detained, Roskomnadzor began blocking the politician’s website navalny.com. The formal reason was Navalny’s refusal to remove the FBK investigation dedicated to Vice President Sergei Prikhodko and businessman Oleg Deripaska from the site.

The investigation was published on the portal navalny.com on February 8, and the very next day, Roskomnadzor, by decision of the Ust-Labinsk District Court of the Krasnodar Territory, entered into the Unified Register of Prohibited Sites the address of the investigation on Navalny’s website, its version on the YouTube channel and a number of news publications covering it. The court made the decision as part of the lawsuit of entrepreneur Oleg Deripaska against model Nastya Rybka (Anastasia Vashukevich) and writer Alex Leslie (Alexander Kirillov) for publishing materials about his personal life without permission: Navalny’s investigation included data from open sources, including from the book and the Instagram account of Rybka, according to which the model was vacationing on a yacht in Norway in the company of Sergei Prikhodko and Deripaska himself.

As interim measures on the claim, the court ruled for the removal of the materials within three days, warning that otherwise the sites on which they are posted will be blocked. In addition, on the day the site navalny.com was blocked, Navalny was broadcasting on YouTube — immediately after the end, the platform blocked the recording, citing copyright infringement.

Navalny filed a lawsuit against Roskomnadzor in connection with the blocking, but it was not satisfied. Soon the politician’s team removed the investigation from the site navalny.com, and after 5 days it was unblocked. «We believe that we resisted the blocking finely and the exercises were successful, » the opposition figure said, commenting on the decision to remove the material.

The «exercises» of Navalny’s team came in handy really soon. In parallel with the campaign to boycott the presidential elections, the politician launched the Smart Voting project in early 2018 — his strategy aimed at the protest electorate was to reduce the number of victories of United Russia candidates in municipal elections scheduled for 2019. In December 2018, the project’s website on domain 2019.vote was blocked by Roskomnadzor.

The head of the supervisory agency, Vadim Ampelonsky, said that the department had allegedly received complaints from several people that the site «illegally processes their data.» The formal reason was precisely this: according to Roskomnadzor, the privacy policy for processing personal data was not spelled out on the site.

Navalny filed a complaint about the blocking, and during its consideration, the opposition members explained that they do not work with personal data at all. However, representatives of the agency stated: information about users who did not register on the site was processed through Google Analytics and Yandex.Metrica services. At the same time, «the collected data was held on Google servers located in the USA» — from the point of view of Roskomnadzor, the site administrator in this case had to either provide the agency with a certified consent to the processing of personal data, or store the information on Russian servers. After blocking, the Smart Voting website moved to the domain appspot.com — a cloud platform supported by Google.

2021: recognition as extremist organizations, mass blocks

Against the background of Navalny’s poisoning in August 2020, his return to Russia in 2021, the publication of the «Palace for Putin» investigation, the replacement of the politician’s suspended sentence with a real one and the protests associated with all these events, the blocks again became an additional tool of pressure on the opposition politician and his associates. By the beginning of 2022, all sites affiliated with Navalny and his team had been blocked in Russia.

The blocks of 2021 can be divided into two streams: some were part of the process of combating Navalny’s structures themselves and recognizing them as extremist organizations; others, apparently, served to deprive potential voters of access to the Smart Voting website.

Interestingly, the Smart Voting project was blocked even before the FBK and Navalny’s regional offices were recognized as extremist organizations (this happened on June 9). For example, on May 6, YouTube sent out warnings to platform channel owners Vladimir Milov, Denis Styazhin and Ilya Yashin, as well as to Novaya Gazeta and SOTA media outlets about the prospect of blocking due to links to «Smart Voting», which the organization regarded as «spam, lies and fraud.» However, on the same day, the platform recognized the claims as erroneous, restored the deleted content and apologized to users.

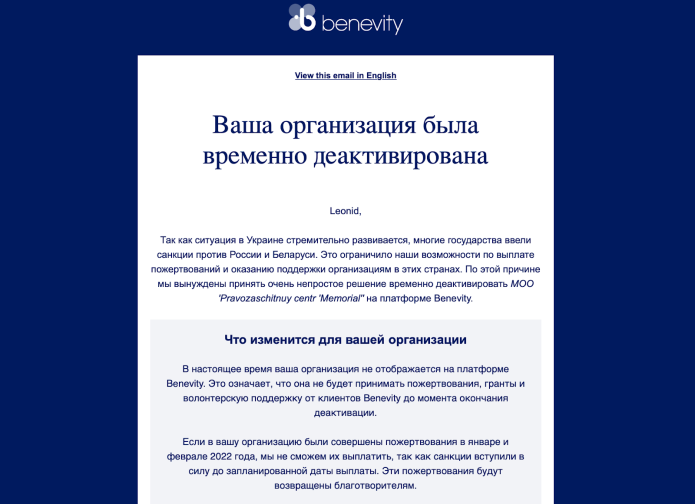

By July 26, 2021, after Navalny’s structures were recognized as extremist, almost all sites associated with them had been blocked. Among them is the website of the opposition figure himself, navalny.com, the pages of the FBK and Navalny’s regional offices, the websites of his associates Leonid Volkov, Lyubov Sobol and Oleg Stepanov, the pages of the RosYama and RosZhKH projects, as well as the website of the Alliance of Doctors (which was not formally connected with Navalny in any way), and others. Leonid Volkov named the total number of blocked portals — 49 (according to Roskomsvoboda — 54).