This article was produced in a collaboration with Daraj Media. Read the Arabic version of the article on their website or check out their English-language page.

When I was a kid, I had to keep a big secret: I couldn’t tell anyone that my dad is Arab and Muslim.

I grew up in a tiny town in central Russia where most people were ethnically Russian and Orthodox Christians. Until I turned 17 and moved to Moscow for university, my mom made me keep this one part of my identity hidden, even from my closest friends. I cannot blame her — she wanted to protect me. And I understand her better with time.

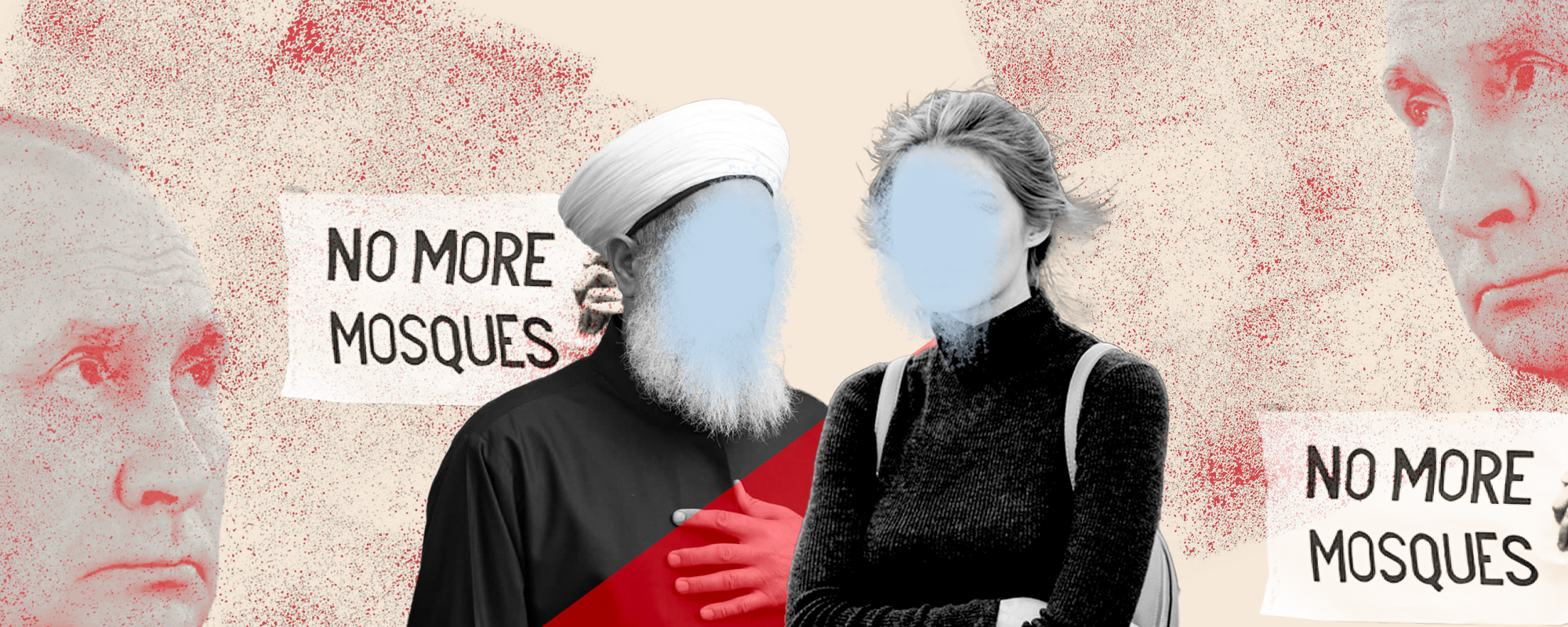

Despite Russia’s official talk about multiculturalism and interfaith harmony — the narrative often touted by the government — the reality on the ground in the 1990s and 2000s was very different. Even after the Soviet era, with its proclaimed «friendship of peoples,» the Russian society was largely xenophobic and Islamophobic.

You might ask if things have improved over the past twenty years. Sadly, the answer is no — if anything, they’ve worsened. Why? Among the reasons, the Russian state fuels Islamophobia, promotes aggressive Russification and, what this article looks into, persecutes Muslims — usually behind the scenes and with little media attention.

Islam and Muslims in Russia: What You Need to Know

Did you know that Islam is no less prominent in Russia than Orthodox Christianity? In fact, Russia is home to the largest Muslim population in Europe.

«It is openly said that Russia is not only an Orthodox, but also a Muslim country. Living in the country today are more than 20 million Muslims, including members of more than 30 indigenous Russian nations,» said Talib Saidbaev, advisor to the Head Mufti of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Russia. Over 15% of Russians are Muslims, which makes Islam the second-largest religion after Russian Orthodoxy.

In 2019, Chief Mufti Ravil Gainutdin predicted that by 2030, one-third of Russia’s population could be Muslim. The 2020 census showed a 4,9% decrease in the ethnically Russian population compared to ten years earlier. At the same time, populations in predominantly Muslim regions like Chechnya have been growing, with Chechens increasing by 17,1% during the same period.

Muslims are spread all over Russia but are mostly concentrated in several regions. The largest communities live in the North Caucasus region — particularly Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia. Many Muslims also reside in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, republics in the Volga region. Russian Muslims come from various ethnic groups, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Chechens, Ingush, Avars, and many others.

Most Russian Muslims follow Sunni Islam, especially the Hanafi school, but Sufism also has a strong presence, especially in the North Caucasus. Sunni Muslims are represented by the Council of Muftis of Russia, which brings followers together to talk about their faith and discuss community issues — like religious freedom, or how Islam fits into modern Russian society.

Islam has been a part of Russia’s history for over a thousand years. During the Soviet era, though, religion — including Islam — was repressed. The officially atheist government closed mosques, shut down religious schools, and generally tried to suppress Islamic practices. Despite this, many Muslim communities kept their faith alive in secret. Since the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, Islam has made a big comeback in Russia. New mosques have been built, and Islamic education has seen a revival. None of this would have been possible without the new Russian Constitution, which officially recognizes freedom of conscience and religion, paving the way for religious and cultural diversity.

Russian Legislation: Multiconfessionalism and Multinationalism

«We, the multinational people of the Russian Federation» — this is how the 1993 Russian Constitution begins. It’s fitting since Russia is officially one of the world’s largest multinational countries, home to over 190 ethnic groups.

The Constitution, adopted after the Soviet Union collapsed, drew from best practices of democratic countries’ constitutions and was heavily based on international law standards. It promises equal rights for different ethnic groups and guarantees respect for human rights regardless of race, nationality, language, origin, or religious affiliation, prohibiting any form of discrimination. Article 26 states that everyone has a right to determine and indicate their nationality — a significant shift from the Soviet era when indicating nationality on passports was mandatory.

Article 28 ensures freedom of conscience and religion, allowing everyone to practice any religion or none at all. This provision supports Russia’s rich diversity of faiths, including Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, and more. Legally, Russia backs its multicultural promise with laws such as the Federal Law on Indigenous Peoples' Rights. These laws protect indigenous groups and other minorities, preserving their cultural heritage and granting some autonomy.

While everything looks good on paper, there is a significant gap between law and practice. For Russian minorities, it’s not just a matter of lax enforcement — discrimination is a consistent state policy.

In Breach of the Constitution: Suppression of National Cultures and Russification to Combat Separatism

While the Russian constitution promises to protect native languages and cultural heritage, ethnic minorities often find themselves at a disadvantage. State schools usually prioritize Russian over minority languages, which slowly but steadily erodes linguistic diversity in the country. In many places, teaching native languages is minimal or even non-existent, even though the law says it should be protected.

The Russian government covertly implements a Russification policy by promoting a single Russian national identity at the expense of minority cultures and languages. The state purposely imposes the Russian language and mainstream culture to overshadow minority traditions and customs. This not only undermines Russian vibrant cultural diversity but also breeds resentment and alienation among ethnic minorities, creating fertile ground for separatist movements. Yet, the Kremlin made it clear for all ethnic minorities: crush any separatist ideas or your cities will be reduced to rubble — like Grozny, the capital of Chechnya.

In the 1990-s and 2000-s Russia witnessed some of the most violent conflicts on its territory. However, the Kremlin discourages Russians from calling them wars — they are commonly referred to as Chechen campaigns. The First Chechen War (1994-1996) started as a separatist conflict after Chechnya declared independence from Russia and ended with a tense ceasefire, where the central government did not fully withdraw the troops. The Second Chechen War (1999-2000), in contrast, was waged under the slogan of a «counterterrorism operation.» There is documented evidence that this «operation» not only targeted terrorists, as identified by the Kremlin, but was in essence a large-scale military campaign, which included heavy indiscriminate bombings of civilians. Human rights organizations documented widespread abuses, including torture, disappearances, and extrajudicial killings — from both sides.

Under Putin, the Kremlin gained control over the republic. To quell separatism, root out radical Islamism and preserve stability in the region, he chose the notorious Ramzan Kadyrov as the future leader of the Chechen republic. Many Muslims around the world know him as a champion of Islam and rights of Muslims in Russia. In reality, he might be the greatest threat for Chechens, if not for all Russian Muslims. Kadyrov aggressively targets «Wahhabis,» a term he loosely uses for any Muslims who oppose his regime. He tortures and kills Russian Muslims, and Chechens in particular, while portraying them as violent, brutal and ruthless. In doing so Kadyrov and Putin sen a clear message to the world: accepting Chechens as refugees is dangerous. Chechens should reside in Chechnya. A Chechen guerilla leader was even killed in Berlin by a Kremlin agent.

After the Chechen wars, Muslims in Russia were treated with particular caution. If the Chechens were the main scapegoats for the Russian government before 2014, after the annexation of Crimea the Kremlin has found a new convenient victim — Crimean Tatars, a Turkic ethnic group, the majority of whom are Muslim.

Crimean Tatars: Persecution on Religious and Political Grounds. Or Both?

10 years after the annexation of Crimea, there are around 180 political prisoners on the peninsula. Over 110 of them are Crimean Tatars.

Pay attention to these sentences: 18 years for reading religious texts or talking about Islam — whether in the kitchen or in the mosque. 8 years for protesting against the Russian annexation of Crimea.

Most prosecutions on the peninsula target Crimean Tatars affiliated with «Hizb ut-Tahrir,» (Islamist political organization), branded in Russia a terrorist group. Yet, «Hizb ut-Tahrir» remains legal in Ukraine; meaning that with the arrival of Russia in Crimea, members of «Hizb ut-Tahrir» overnight became terrorists. And not only supporters of the organization: post-annexation, the peninsula has regularly seen searches on independent journalists, civil activists, activists of the Crimean Tatar national movement, members of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, as well as any Crimean Muslims suspected of having connections with «Hizb ut-Tahrir.»

Most Crimean Tatars, or «paper terrorists,» as wittily named by Crimean lawyer Emil Kurbedinov, have never held weapons in their hands. In fact, in Crimea, anyone who practices Islam and has an active civic position can fall under the «anti-terrorist roller.» It is not just prison sentences either — a dozen Crimean Tatar activists have been abducted, and none of them have been found to this day. The local government brazenly asserts that «there are no mass disappearances of Crimean Tatars on the peninsula.»

Mass persecutions have also affected Crimean Tatar women. For instance, in August 2018, poet Alie Kenjalieva was accused of «rehabilitating Nazism» for a poem where she condemned the war in Donbass. Many Crimean Tatar women are accused of «inciting hatred or enmity» — just for speaking up.

The war in Ukraine exacerbated the situation. Crimean Tatars see conscription into the Russian army as genocide. While Russian authorities do not disclose exact data on the number of conscripts mobilized in Crimea, local human rights activists claim that Crimean Tatars were disproportionately issued more draft notices than the Slavic population of Crimea. According to calculations by human rights activists from «Crimea SOS,» about 90% of draft notices in Crimea were issued to Crimean Tatars. As Crimean villages empty out, Crimean Tatars are pushed to fight against Ukraine — a country they used to call home just 8 years ago. Actually, many of them still do.

Since many Crimean Tatars indeed opposed the annexation of Crimea, the Kremlin initially tried to negotiate with the Crimean Mejlis and even co-opt it, but this did not work out. Then, the Mejlis was declared an «extremist organization» in Russia. Natalia Poklonskaya — known for targeting Crimean Tatars as the former chief prosecutor— called the Mejlis leaders «puppets in the hands of large Western puppeteers» who use the Crimean Tatar people «as bargaining chips.» According to Poklonskaya, the Mejlis was «exclusively geared towards anti-Russian activities.» Eventually, after the outlawing of the Mejlis, the Kremlin used intimidation and blackmail to negotiate with Crimean spiritual leaders, who now mainly serve to legitimize Russian presence on the peninsula.

The Russian government is trying to create a façade of normalcy and prosperity among Crimean Tatars with lots of money flowing into the republic. But can building new mosques make up for mass persecution?

Epilogue

Ironically, this Russian façade of normalcy extends even to Muslim-majority and Arab nations. Putin succeeds in portraying Russia as an anti-colonial force, contrasting it with the West, yet suppresses its own ethnic and religious minorities. Neither Putin nor, heaven forbid, Kadyrov champion the rights of Russian Muslims — quite the contrary. They weaponize Islamophobia, exploit Islam and its followers for personal gain while relentlessly oppressing Muslim communities and trampling on their rights.

I am not a Crimean Tatar and here in 2024, I can somewhat freely say that my dad is Muslim. But the shadow looms: I live in a constant fear that one day they might come after us, people like me, simply for practicing our faith, for reading our religious texts.

Does my Arab father, who immigrated to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, suspect any of this? I doubt it. Like many around the world, he listens to Russian propaganda that boasts about Russia being so tolerant and harmonious between religions.

But I refuse to let anyone, including Muslims, fall for this facade.

Inna Bondarenko