According to OVD-Info data, the three months of the enforcement of the law on «fakes» about the Russian army have resulted in at least 59 criminal cases and two sentences in different regions of Russia. Reposts on social media, anti-war flyers and even phone conversations can be considered «fakes». OVD-Info analysed how Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code works in practice.

On March 25th, Ingush journalist Isabella Yevloeva got off a plane in a European country, switched off airplane mode on her phone only to receive a flood of messages with words of support from her friends and colleagues. They told her to «remain brave and strong» and expressed their sympathy.

«I got scared that something had happened to my family. In a situation like this, you always think of your greatest fear. Once I realised that this is just a criminal case and everyone is alive and well, I relaxed, ” — the journalist recalls.

This is how Yevloeva learned that she was facing a charge in connection with the article on «fakes» about the Russian army. One month later, they launched another case against Yevloeva. Once again, she learned about it from a messaging app when journalists asked her to comment.

The journalist was prepared for criminal prosecution. She had extensively covered the protests in her republic that started in the fall of 2018 after the heads of Ingushetia and Chechnya signed an agreement on changing the borders. At that time Yevloeva was employed at the national television and radio company «Ingushetia» and was on maternity leave. She was not into politics and dreamt of a children’s project where cartoons would be translated into the Ingush language. However, the silence in the local media about the issue bothered Yevloyeva so much that she started to write about it on her social media. Her accounts became a very rare source of information about the protests against the land transfer. The journalist also attended demonstrations, gathered information and sent it to Russian and international media. She knew the protesters well and shared their stance. With time, Yevloyeva’s social media accounts transformed into an independent media organization called Fortanga and Yevloyeva became its editor-in-chief.

«In the ‘Ingush case’ that led to the sentencing of my associates, I am listed as a participant of an extremist organisation. This is why [the prosecution] was a mere question of time. I, of course, could not have imagined that I would be charged with this particular article, ” says the journalist.

When the criminal charges against Magas protestors were brought forward, Yevloeva was outside of Russia. Fearing her arrest, she decided to stay abroad but to continue covering Ingushetia news.

When the war started, Fortanga started to write about the soldiers from Ingushetia who were sent to Ukraine and to publish lists of those killed and wounded, finding their names in Ukrainian sources. Evloeva says that Fortanga readers did not support the war: «We did an opinion poll. The general sentiment was that this is not our war and there is no sense in the Ingush participating. We have always suffered from the colonial attitude of Russia, so our people can empathise with Ukranians.»

Very quickly, Roskomnadzor started to block any media that wrote about the war not referencing official Russian sources. The editors of Fortanga tried to avoid being blocked and deleted all materials about Ukraine from their website. However, Evloeva continued to post them in her private Telegram channel. These were the posts that resulted in the criminal charges.

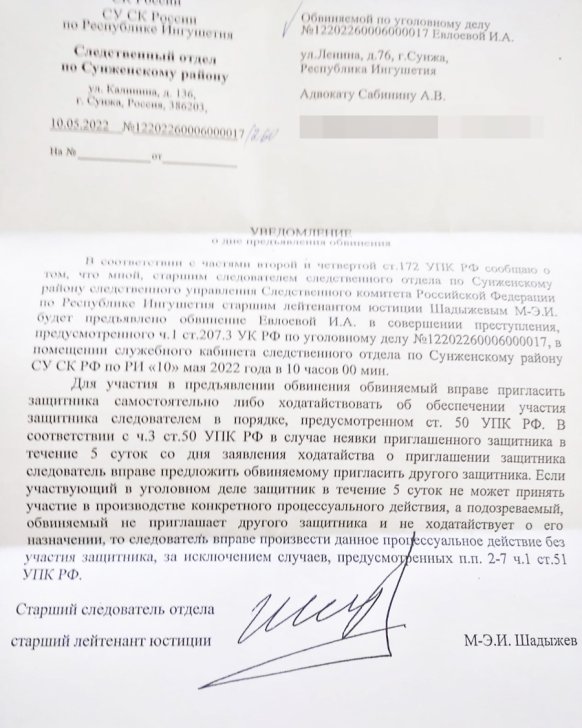

At first, the media reported that the grounds for the first criminal charge was a post made on Yevloyeva’s Telegram channel on March 23rd, where she called the Z sign «synonymous with aggression, death, pain, and unconscionable manipulation.» However, the decision to initiate criminal proceedings (OVD-Info is in possession of the document) mentions two posts that were made between March 5th and 9th. In that period, Yevloyeva twice wrote about Ingushetia residents who were taken hostage by Ukrainian troops, and twice posted the loss reports, as well as her own text about the residents of Ingushetia who died in the war. There was also a post about an open letter with reflections on the situation in Ukraine that might have been authored by an FSB officer. The journalist believes that the police became interested in some or all of these publications. The investigators refuse to reveal the details to Yevloeva’s lawyer, Andrey Sabinin, since his defendant is outside of Russia.

The second case was launched a month later. This time it was concerning a repost of a photo from Bucha with a comment: «The Russian soldiers rape women and girls in Ukraine, kill civilians, rob and loot. When I watch the news, I get so many flashbacks. Nothing has changed since the Chechen war. It is all the same.»

Despite all the precautions, Fortanga was blocked at the end of March. Yevloyeva says the editors still have not received an explanation. In April, the father and the 22 year-old daughter of the journalist were interrogated by the Investigative Committee. The security forces were interested in Yevloeva’s whereabouts and contact details, in the family’s attitude to her activities, and why she was still registered at a house where she had not lived for many years. At around the same time, the government-related Ingush Telegram channels reported that the journalist was put on an international wanted list because of her relation to a case on an extremist organisation. One of the channels wrote: «At the moment Yevloeva is mass producing Ukro-fakes. She thinks the letter ‘Z’ is a new swastika. Let us visit Yevloeva in her dumpster of fakes.» However, the information about her placement on the international wanted list remained unconfirmed. The journalist believes this was merely an attempt to threaten her.

«I don’t really understand the point of launching two identical criminal cases against a person who does not reside in Russia. Probably, this is for threatening others. I think the government is trying to get rid of everyone who speaks up. For instance, we have received a list of 12 names of Ingush residents who were killed in action, while the official media have reported only 4. Our articles have a lot of resonance so they demonstratively start these criminal cases, ” says the journalist.

«So Society Understands»

Several hours after the Russian President announced the start of the war in Ukraine, Roskomnadzor announced that any writing about the war, which must exclusively be called a «special military operation, ” could only use official government sources. The agency threatened to block the websites of, and fine up to 5 million rubles, anyone who did not comply.

This was followed by increased censorship–on February 26, Roskomnadzor demanded that 10 independent media outlets delete publications about the war, threatening to block their websites if they did not comply. Since then, over 3,000 websites have been blocked (as of May 5th, according to data from Roskomsvoboda). Through mid-April, Roskomnadzor had blocked over 117,000 «fakes» about the war, according to a report by the agency’s head.

On March 4, a week after the war began, the Duma increased wartime censorship by passing a packet of amendments to the Code of Administrative Violations and the Criminal Code. These changes created punishments for any statements about the war and the Russian military. In the Criminal Code, a new article was introduced, 207.3–”Public dissemination of knowingly false information about the use of the Russian Federation’s military.» The amendments were placed in a bill from 2018 which had already gone through a first reading. The law went through its remaining two readings in one day, and was immediately unanimously approved by the Federation Council and signed by the President. The law went into effect that same day.

During the discussions of the law, the Speaker of the Duma, Vyacheslav Volodin noted «It’s possible that literally tomorrow those who lie and make statements discrediting our military, will be punished [by the new laws], and very harshly. I want everyone to understand–and society to understand–that we are doing this to protect our soldiers and officers, to protect the truth.»

On April 6, further amendments were made to Criminal Code Article 207.3 to extend criminal responsibility to any false statements about Russian state agencies operating abroad. According to a senior partner of the «Net Freedoms Project«-- a human rights project that has provided defense representation in over 20 cases of «fakes”--the amendments work as follows: «So you write something, for example, about [The Foreign Minister] Lavrov, who is somewhere outside of the country–now this can be grounds for opening a criminal case. But if you write about him before he gets on the plane and leaves the Russian border, then there’s no basis for a criminal case.»

The punishment for disseminating «fakes» ranges from 1.5 million rubles, to a year of community service, to three years of compulsory labor to three years in prison. If the «fakes» are distributed using someone’s official position (section A, part 2), by a group (section B, part 2), with falsified evidence (section V, part 2), motivated by financial gain (section G, part 2), or motivated by hatred or animosity (section D, part 2), the fine increases to 5 million rubles, compulsory labor up to five years, or imprisonment up to 10 years. The most severe punishment is for «fakes» that have grave consequences–up to 15 years imprisonment. The law does not specify what qualifies as grave consequences. To date, there are no known criminal cases being investigated under this part of the code.

The first criminal cases under the new code occured on March 16–two cases were opened in the Tomsk region and one in Moscow. As of June 14, there are at least 59 cases with respect to 58 defendants. The first sentence was handed down on May 30 by a court in the Zabaikal region. Peter Mylnikov, a resident of the village Olovyannaya, was fined 1 million rubles. According to the investigation, he distributed two documents on a Viber chat which contained information that turned out to be false–in one, it said that they would send Young Army Cadets to Ukraine when they reached 18, and in the other, that bodies of soldiers killed in action would be burned. Mylnikov admitted his guilt, although he did not deny that he did not support the war.

The second sentence was handed down on June 3 in Crimea to Andrey Samodurov, an employee of the Ministry of Emergency Situations. Based on information from the Telegram channel «Baza, ” he allegedly went door-to-door announcing an emergency evacuation to Yalta residents saying that «The US has already sent rockets and planes» because of the war in Ukraine. His punishment was not announced. Based on the information from the court website, his case was heard in its entirety in one hearing. Usually court hearings that brief indicate that the defendant has agreed to a special procedure [plea bargain] for hearing the case.

According to Stanislav Seleznev, the Investigative Committee uses the same practice for cases under Article 207.3 as they did for cases about «coronavirus fakes» (Article 207.1–”Public dissemination of knowingly false information about circumstances that pose a threat to the life and safety of citizens»). Convictions under this article were also determined in a special procedure if the defendant admitted guilt.

«Investigative work on these cases has a key feature: immediately after the arrest, or during the first interview of a witness, or interrogation of a suspect, they try to convince the person to admit that they made the statement. As a rule, almost no one denies this. And then with that done, they propose that the person sign a voluntary confession and also confess to the rest of the ‘bouquet’–including that the statement was made ‘knowingly’ and ‘falsely.’ The person, suddenly realizing what has happened, decides to formally confess to the police themselves. And only after they receive the voluntary confession do they invite in the lawyer, as a rule, a court-appointed one, ” explains Seleznev.

«Discrediting» or «Fakes»?

In addition to the statute on «fakes, ” another law was also passed on March 4th prohibiting «discrediting the Russian armed forces.» The first «discrediting» offense receives an administrative punishment, whereas the second becomes criminal. The problem is that frequently, similar activities are considered by the authorities to constitute both «discrediting» the army and also «fakes» about the army. The guiding criteria for police and investigators are opaque.

Like Isabella Yevloyeva, media manager Ilya Krasilshik also published a post about Russian soldiers killing civilians in Bucha. A criminal case was also opened against him for «fakes.»

OVD-Info is aware of at least 18 instances when people were charged with «discrediting» for posts about what happened in Bucha. For example, a Moscow man reposted a long entry on his VKontakte page which contained the following text: «On Sunday, all of America learned about the monstrous crimes against humanity committed by Russian barbarians in Bucha, about a genocide–a mass murder of people for one reason only, because they were Ukrainian, citizens of a free Ukraine.» He was fined 45,000 rubles for the administrative violation of «discrediting» (OVD-Info is in possession of the court decision).

Among the criminal cases charged under the statute on «fakes» at least four have been for posts about the number of Russian soldiers killed in the war. At least three administrative cases for «discrediting» have been opened for posts on the same topic.

One Ulyanovsk resident sent several messages in a closed group chat including: «They are shooting at kindergartens and maternity hospitals. More than 60 children have already died, ” and «Our Ulyanovsk battalion, located near Kiev, has almost been completely destroyed. 300 dead bodies have already been transported out.» He was fined 30,000 rubles (OVD-Info is in possession of the court decision).

Dmitrii Baev, a deacon of the Ioann Predtechi Church of the Nativity, published a post on VKontakte stating that Ukrainian soldiers had «sent 17,500 orks to the underworld, ” and also called Russian soldiers occupiers. A criminal case was opened against him. Information about the number of Russian soldiers killed in action was also posted on social media by Kostroma resident Alexander Zykov. Citing Alexey Arestovich, advisor to the Ukrainian President, he wrote about the destruction of the 331st Guard Airborne Assault Regiment from Kostroma. A criminal case was also opened against him.

In total, OVD-Info reviewed 900 available decisions on the «discrediting the army» statute. In around 100 of them, judges cite the unreliability of the information being distributed, but classify the offense as administrative. There is no clear delineation between the application of Criminal Code Article 207.3 and Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Violations, notes Daria Korolenko, a lawyer at OVD-Info: «It appears that whichever agency finds it first, that’s the type of case they’ll open.» Currently the analysts at OVD-Info are researching the implementation of these statutes and have published preliminary findings on their Telegram channel.

«At first we thought that criminal cases would be mostly used for publications on the most difficult topics, for example posts on Mariupol or Bucha. Those criminal cases certainly do exist, but at the same time, people are charged with ‘discrediting’ for almost identical posts, ” said Korolenko.

She believes that one of the biggest problems with the statute on «fakes» is its vague terminology: «Over half, if not all, of the criminal cases under 207.3 could have easily been considered discrediting. The wording in the text of the law is too broad. It’s possible that when there is more court practice on these laws that some sort of logic will become clear. However, I am sure that it’s completely random, which creates additional danger: you post something on the internet and don’t know whether a criminal investigator or a beat cop will knock on your door.»

A recent interview with Sergey Kiriukhin, an investigator from the Lipetsk region’s Investigative Committee, published on the agency’s website supports this: «Speaking in simple terms, any publicly available publication on social media, news media, or the internet saying anything about the activities of the Russian army that is not confirmed by the Ministry of Defense or some other official source (President, government, ministries and agencies), can be considered knowingly false information, the distribution of which can lead to criminal liability.»

The logic of the statutes on «fakes» and discrediting the army is that the first punishes for disseminating facts and the second, for opinions, says Stanislav Seleznev. At the same time, there are cases where the new norms are applied arbitrarily: «If we say there is no such division, we need to admit that cases are opened chaotically. Perhaps this is not entirely true. There are isolated incidents, because investigators have not yet learned the methods for investigating them, especially since under Criminal Code Article 207.1 [«coronavirus fakes”], there were few cases throughout the country. There were also quite a few errors that popped up, and they had to either reclassify the cases or close them.»

Phones and OMON–what else counts as «fake»?

The first known defendant in a criminal case on «fakes» who has been jailed was a driver for the Moscow MVD Sergei Klokov. He was born in Irpin and lived for some time in Bucha. His relatives and friends are still in Ukraine and at the beginning of the war, Klokov’s father evacuated from the Chernigov region to Germany.

According to the investigation, while on the phone with a police colleague, Sergei Klokov said that Russia was underreporting the numbers of soldiers killed in action and wounded soldiers evacuated to Belarus, that Russian soldiers were killing civilians in Ukraine and that Ukraine «is not run by Nazis.»

Klokov was charged with spreading knowingly false information about the Russian military by a group of people, using his official position, and motivated by hatred (Criminal Code Article 207.3, section 2, parts a, b, and d) and arrested. According to the investigators, the hatred contained in Klokov’s actions was directed towards the «Russian people.»

According to his lawyer Daniil Berman, the evidentiary base of the case rested on a wiretap of Klokov’s telephone, which law enforcement started listening in on several months before the war began. These investigative actions were carried out in connection with a criminal case opened in the early 2000s, which Klokov had nothing to do with.

The investigators considered three phone conversations with different people in one day to constitute public dissemination of information. «The logic is the following: if you make three phone calls, that means you have disseminated it to three people, which is more than two, and that means the information was disseminated publicly, ” explains Berman.

During the first interrogation, Klokov refused to admit guilt, but during the second interrogation he did. Berman thinks that his defendant was pressured to confess.

After his arrest, lawyer Vladimir Markov came to visit Klokov in the police station and told him that he would represent his interests for free. According to Berman, Makarov was not a court-appointed lawyer, since the case materials contain an order which shows that he was individually contracted: «This lawyer recommended that [Klokov] admit guilt and not make a scene, otherwise things would be worse. He went to court with that lawyer for the pre-trial detention hearing and the judge decided to keep him in pre-trial detention. The lawyer’s speech in the courtroom was accusatory in tone.»

Specifically, Makarov said that Klokov was in a «compromised» mental state, and that the Criminal Code article that he was being charged with was «necessary as a warning» because he had «acted poorly» towards his people and «been a burden» to them.

«Klokov’s ‘our guy, ’ he’s a Soviet guy, he’s not an enemy of the people. Did he mess up? Yes, but not out of malice, he ‘lost his mind, ’ his psyche couldn’t stand it. Throughout the past few days the investigators and I both saw that he was disoriented, zombified, that his psyche was distorted and his perceptions inflamed. We had to take it slowly to even talk to him. And so, the fact that he needed to cooperate with the investigation, that he needed to say that what he did was wrong, he didn’t understand that, he had different information in his head, ” stated Makarov in court.

Several days after his arrest, Klokov’s mother contacted Berman and asked him to take the case. In the temporary detention facility, Berman was first told that Klokov had refused his services without presenting any documentation of the refusal. Finally, Klokov separated from his first lawyer and signed a contract with Berman.

Klokov also told his new lawyer that police threatened to open a criminal case against his mother and wife as collaborators. Their bank cards were confiscated during the search of his home and then blocked. According to Berman, the investigators did not explain why the cards were blocked.

The lawyer thinks that there will be a conviction despite all of the violations: «I’m certain that if nothing in the country changes, in a global sense, then all of the accused or at least the majority of them, including Sergei, will be convicted. At this point it’s impossible to say what kind of sentences they’ll receive, but they’ll all be found guilty. They didn’t pass this law only to later acquit people and dismiss criminal cases.»

If in Klokov’s case the public dissemination was the result of a personal conversation, in the case of Khakassia journalist Mikhail Afanasev, the «fakes» about the army were actually about OMON and Rosgvardia. An article entitled «‘Refuseniks’ or why 11 Khakassia OMON and Rosgvardia officers refused to participate in the ‘special operation’ in Ukraine» was published in Novyi Focus at the beginning of April.

Several days later law enforcement came to editor-in-chief Mikhail Afanasev’s, home to conduct a search. It soon became clear that there had been a criminal case opened against the journalist for disseminating «fakes» using his official position (Criminal Code Art. 207.3, section 2, part a). Afanasev was arrested. Any media outlets that reprinted the article from Novyi Focus were blocked by Roskomnadzor.

Even though the material did not contain any information on the military, Afanasev was charged with «fakes» about the army. At the time the article was published, the statute on «fakes» only covered the Russian military. The broader formulation, which includes «state agencies, ” was not yet in use.

«The basis for the criminal investigation was a report from a well-known expert witness, Olga Yakotsuts, who has proven to be controversial, for example in the case of Svetlana Prokopyeva. To the question of whether Afanasev’s publication contained statements about the Russian army, the expert answered that yes, there are statements about the Russian army in the form of descriptions about OMON. The level of her reasoning was outrageous. One line and nothing more. I mean, a linguist is not required to know the laws on defense and how to differentiate between different troops. Nevertheless, exceeding the boundaries of her credentials, she answered the question in the affirmative, ” explained Stanislav Seleznev.

«To Silence Everyone»

On June 7, the house belonging to Isabella Yevloyeva’s 70-year-old parents in Sunzha was searched. This wasn’t the first time. In 2019, the police spent six hours searching the home of the journalist’s mother and father, surrounded their house with military vehicles, and blocked entry. By then, the threats to Yevloyeva’s family had already caused her to resign from her position as Fortanga’s editor-in-chief and emigrate from Russia.

«They told me then that my children would have problems, ” Yevloyeva said. «They were in Russia, while I was already in Europe. But then [the head of Ingushetia Yunus-bek] Yevkurov resigned. During that time, I managed to get my [three youngest] children out of the country and to return to my profession. Now they are pressuring me through my parents, searching and interrogating them, ” said Yevloyeva.

The pretext for the new search was a case on «fakes». The police confiscated the Yevloyevs’ phones and, once again, asked them about their daughter’s whereabouts, the reason why she was registered at this address, and their thoughts about her work. In her Telegram channel, the journalist wrote that after the encounter with the police her parents stopped responding. She later learned that her mother had had a hypertension emergency and was transported to the hospital after the search was finished.

«My Mom has had high blood pressure every day since then. She is a trooper. She hangs in there and keeps it together. But her body responds to the stress. It’s not just the search though. My parents live in constant fear for my life. They know that my colleagues are in prison and understand that I should be there with them but that, by pure accident, I ended up abroad, ” Yevloyeva said.

The journalist does not consider herself guilty and insists that she has not disseminated any false information. All the information that Fortanga reported and Yevloyeva posted in her Telegram channel went through multiple rounds of fact checks. She said that the information about the war casualties and prisoners came from valid sources: «I had the names of servicemen, the military regiments they served in, their years of birth, and all the other information about these people. I fact-checked everything. I didn’t make it up. This is ridiculous. There are indeed people who deliberately spread false information in Russia. It’s our government, our president. They know that they’ve been lying to us for many years, and they keep doing it. They accuse other people, ordinary people, of all the things that they do themselves.»

According to senior partner of the Net Freedoms Project Stanislav Seleznev, in the cases on «fakes, ” the investigators do not try to prove that the information is «knowingly false.» «To prove the ‘knowingly’ part, they need to prove a whole set of circumstances—that the person was absolutely sure that the information was false and spread it to misrepresent the facts. Instead, the investigators urge suspects to plead guilty, ” he explains.

Investigations are based on the law stating that accurate information can only come from government sources and the rest is «fake.» Seleznev notes that there are only two ways to prove that the information is not false—to prove that the Ministry of Defense is lying or to prove that the author of a publication had no doubt that their information was accurate.

The first option is hardly realistic under the current circumstances. And the second option is interesting, because it requires subjective evaluation. For some people, only the Ministry of Defense posts can be trusted, while other people think that the BBC offers truthful information. The problem is that [these sources] often contradict each other. During the war, this is completely expected, considering that the Ministry of Defense is one of the sides of the conflict. Ultimately, the arguments during criminal case hearings on «fakes» end up being about ‘posts vs. posts, ’» the lawyer said.

Aside from Isabella Yevloyeva’s two cases, the article on «fakes» has been used in Ingushetia against blogger Islam Belokiyev. He talks about the problems in the region in his accounts on YouTube and Telegram, criticizes the Russian and Ingush authorities, and opposes the war in Ukraine.

«For the smallest republic in Russia, three ‘fake-news’ criminal cases are a lot, ” Yevloyeva said. «In the neighboring regions everything has been suppressed; in comparison, there was still some life in Ingushetia. Some protest mood remained after the wave of repression against our society. That’s why they want to shut us up, to silence everyone. And, overall, they are succeeding. Fortanga is the only media outlet in the region that reported on hot topics, but now they want to shut it up as well.»

Since the police search, Yevloyeva has not published any new posts on her channel. The journalist said that she’d been told through a relative that as long as she writes about Ingushetia, her parents won’t be left alone.

«My family has been taken hostage. Their well-being and peace of mind is being traded [for my silence]. I am being forced to stop writing and to practice journalism. I think about it all day every day, and I can’t make a decision. First, I think I should agree to their conditions for the sake of my family. Then I think that I can’t do it because it is unfair. I understand that the world is unfair. But when you know that you are right, and when you are being blackmailed and pressured in such a despicable way, it is very difficult to make a decision, ” the journalist said.

Yevloyeva emphasized that her family does not intend to leave Russia, and Fortanga will keep operating even without her: «My Mom and Dad say that they are too old to leave, that they don’t have much time left and want to stay on their native soil. It may be hard to understand for some people, but our people are very attached to their land. And then, even if they leave, there’ll be my daughter with her family, and she will have a baby soon. There’ll be my brothers. Fortanga is a grassroots publication, created by activists during popular protests. Whatever decision I make, there will be people who will continue the work.»