Доклад на русском языке: Нерешенные в 2020 году проблемы со свободой собраний в России

Introduction

General

1. On 20 April 2020, Human Rights Centre Memorial (hereinafter, «Memorial») and OVD-Info filed a submission under Rule 9.2 to the Committee of Ministers on the implementation of the general measures in case № 57 818/09 «Lashmankin and others v. Russia, ” (hereinafter, «Lashmankin»). In that submission Memorial and OVD-Info provided a detailed description of the problems existing in Russian law and practice concerning the issue of freedom of assembly. Memorial and OVD-Info have also made a detailed list of recommendations.

2. The current submission is an update to the submission of 20 April 2020. This submission has been prepared by the following Russian NGOs working, inter alia, on the issue of the freedom of assembly in Russia and related issues:

- Human Rights Center Memorial,

- OVD-Info,

- Committee against Torture, and

- Public Verdict Foundation.

3. In this submission we will mainly focus on Lashmankin’s case but will also examine some related issues from other cases, including «Tomov and others v. Russia», «Fedotov v. Russia», «Mikheyev v. Russia», «Atyukov v. Russia». The details about these issues are submitted in the Annexes and will aso be submitted separately under the relevant groups.

4. Below we will:

- describe the developments of the situation in law regarding freedom of assembly in Russia that occurred between April 2020 and April 2021

- describe the development of the situation in practice

- describe the efforts that we have undertaken at a domestic level to implement the ECHR’s judgment in Lashmankin and the authorities' reaction to these efforts

- provide our further recommendations.

Summary

5. We state that many problems, indicated by the ECHR in Lashmankin, have not been tackled by Russian authorities. Furthermore, the situation with regard to freedom of assembly in Russia, in both law and practice, has become more severe.

6. The 2020 Amendments to the Public Events Act created more restrictions; new criminal liabilities were enacted for participants of gatherings, and in January and February 2021, protesters faced unprecedented crackdowns all over Russia.

7. The facts that will be described in this submission demonstrate that problems with freedom of assembly in Russia are not an unintended side effect of reforms meant to implement the ECHR’s findings in Lashmankin. Russian authorities have deliberately implemented additional restrictions to send a message of intolerance regarding peaceful assemblies.

8. The Committee of Ministers has twice provided the Russian government with recommendations for the implementation of the ECHR’s judgment in Lashmankin. The recommendations included legislative reforms and changes to the practices of relevant municipal authorities, the police, and the domestic courts.

9. Instead of reform, the action plans of the Russian government were primarily limited to the following:

- translation and dissemination of the ECHR Judgment in the case of Lashmankin;

- discussions, meetings, conferences, and workshops on this issue;

- preparation of methodical recommendations and so on.

10. We definitely welcome such measures, but it is clear that they are insufficient. In its action plans, the Russian government also mentioned the Constitutional court judgment concerning territorial bans for public events and the resulting liberalisation of relevant regional legislation, as well as the Resolution of the Supreme Court Plenum on public events dated 26 June 2018.

11. Below we provide data that depict the mixed result of the Constitutional court judgments. Moreover, not all regional legislators consistently implement the liberal findings of the Constitutional Court in their legislation (see Section 2(d) below).

12. The problems with the Resolution of the Supreme Court Plenum on public events and its real implementation are analysed in detail in Memorial and OVD-Info’s previous submission.

13. We believe that to improve the situation and to implement the Court’s findings in the Lashmankin case, the Government should change restrictive laws and law enforcement practices. We present our suggestions on this issue below.

Communication following the submission of 20 April 2020

14. On 20 April 2020, with the assistance of European Implementation Network (hereinafter — EIN), «Memorial» and OVD-Info filed a Rule 9.2 submission on the implementation of the general measures in Lashmankin.

15. On 3 September 2020, the Committee of Ministers issued a decision with an assessment of the implementation of Lashmankin by Russian authorities. It stated that the few positive measures taken by Russian authorities were insufficient to achieve tangible progress.

16. The Committee of Ministers has also provided some recommendations to the Russian authorities. It recommended reducing local authorities’ discretion on planning assemblies, demonstrating tolerance to peaceful assemblies, repealing laws that mandate criminal charges against the participants of peaceful assemblies, legislating reasonable fines, and not applying the same restrictions to solo demonstrations as to mass demonstrations. The Committee of Ministers has also decided to return to the examination of this issue in June 2021.

17. After the Committee of Ministers’ decision was issued, Memorial and OVD-Info began to gather a coalition of NGOs to appeal to the Ministry of Justice. On 3 December 2020, eleven Russian NGOs dealing with freedom of assembly submitted their suggestions to the Russian Ministry of Justice. In particular, they asked for the creation of an expert group to advise the Ministry on general measures aimed at ensuring the full realization of the right to freedom of assembly in Russia.

18. However, in its response, the Ministry of Justice rejected any help.

19. Memorial and OVD-Info sent a request to support their proposals to the Russian Commissioner for Human Rights, to all parliamentary parties, and to the large non-parliamentary parties, so that they could participate in resolving the problems identified in the Lashmankin case, and invited them to tackle the problem at the level at which they have representatives (in regional and municipal representative bodies). The Russian Commissioner for Human Rights has not responded to this request directly yet. At the same time, she issued the yearly report in which she raised some issues related to freedom of assembly. In particular, she suggested improving the notification procedure for holding public events, as well as reducing territorial bans for public events in the regional legislation. Additionally, the Russian Commissioner mentioned that article 212.1 of the Criminal Code (repeated holding or organizing of unauthorized protests) should be amended.

20. To date, no initiatives or suggestions for communication have been made by the Russian official bodies.

1. Legislation on freedom of assembly

Necessary reforms not adopted

21. To date, Russian authorities have not adopted any changes in legislation necessary for the implementation of the Lashmankin judgment. For instance, the following measures still have not been taken:

- Spontaneous assemblies are still not authorised in Russia, even if they are peaceful, involve few participants, and create only minimal or no disruption of ordinary life.

- The time-limits within which organisers should notify authorities about public events is still not flexible.

- The authorities still have wide discretion to refuse to approve assemblies in many regions. There are still no legislative criteria as to what constitutes a well-reasoned rationale for a refusal to approve a public assembly. The law still does not provide that assemblies may be refused only if «necessary in a democratic society», and therefore does not require any assessment of the proportionality of the non-approval, which leaves a wide discretion to the authorities.

- The regional norms often remain restrictive.

- The police still have the right to detain individuals for participation in peaceful spontaneous assemblies not authorised by the authorities.

- The administrative fines for participation in peaceful assemblies not authorised by authorities are still very high.

- The courts still have the right to sentence people to administrative arrest for participation in peaceful assemblies not authorised by authorities.

- There is still criminal liability for participating in multiple peaceful assemblies not authorised by authorities, although this issue was considered several times by the Russian Constitutional Court.

Additional restrictive laws

22. During the last year, several new laws were adopted in Russia that additionally restrict freedom of assembly. The following new restrictions have been adopted:

- Foreign and anonymous funding of public events have been completely prohibited, as well as funding from the Russian NGOs recognised as foreign agents. There is now a requirement to provide additional financial statements indicating the organizer’s bank account details when submitting a notice regarding a rally with more than 500 participants. It is also obligatory to provide passport details when transferring funds to organize such a rally. A liability has been introduced for rallies’ organizers and donors who have violated the regulations regarding the prohibition on foreign and anonymous funding of rallies.

- The organizer of a rally is obliged either to agree with an alternative place and time proposed by the authorities, or to not conduct said rally.

- The period within which the authorities must respond to the notification regarding a public event has been extended for cases in which the deadline for reply is on the week-end.

- Additional territorial bans have been introduced on holding rallies near buildings occupied by emergency response services, which include the police and the federal security service (FSB). Moreover, a complete list of such services is established not by law, but by local government order.

- A uniform press badge, approved by the authorities, has been introduced, which must be worn during a public event. There is also now a liability for journalists for the illegitimate wearing of the press badge during rallies, which creates grounds to prosecute journalists under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code in case of repeated violations.

- The right to call for participation in a public event has been limited. Social network owners are obligated to block information about unauthorized public events and there is an administrative liability for violation of this requirement.

- The courts have been given discretion to recognize a picket line or rotating solo demonstrations as an unauthorized collective public event.

- The punishment has become harsher for defiance of a police officer’s legitimate order under article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative procedure.

- Amendments to Article 267 of the Criminal Code («Interfering with Transport Vehicles or Communications») have been made. Due to changes in this article, criminal liability is now possible even for formal violations without the occurrence of negative consequences. Moreover, this Article may be applied not only in cases of blocking roads for cars, but also for pedestrians. The authorities have already enforced this Article in numerous cases.

- Article 213 of the Criminal Code («Hooliganism») has been amended, and now provides for the application of this article in the case of a gross violation of public order «with the use or threat of violence against citizens». The fear is that «threat of violence» is a vague term, and it is not clear what it will mean in practice. In addition, the second part of this article will also extend to the actions of a «group of persons». Prior to the amendments, the law referred only to a group of persons acting in concert by prior arrangement or to an organized group, which implied that the initial intention of those charged was the commission of unlawful acts. Now it may apply to any group of citizens, not united by an unlawful purpose, but who nonetheless violate public order.

Draft laws under consideration

23. Some deputies of the Russian Parliament proposed several draft laws that could potentially improve the situation with regard to freedom of assembly in Russia. For instance, they made the following proposals:

- To abolish Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code that allows criminal prosecution of individuals for participating in multiple non-authorised peaceful assemblies.

- Not to punish individuals whose only violation was participating in a non-authorised assembly.

- To abolish Article 20.2.2 of the Administrative Code that allows the punishment of individuals for their simultaneous presence in a single place, which can be considered participation in a mass assembly.

- To authorize the wearing of masks by participants in mass assemblies, as well as other gear designed to protect individuals against COVID-19 which is forbidden under current legislation.

- To introduce administrative responsibility for authorities’ refusals to allow mass assemblies.

24. Unfortunately these positive proposals are not currently supported by the majority of the Russian parliament.

Practice of the Constitutional Court and its consequences

25. The rulings of the Russian Constitutional’s Court on the freedom of assembly are quite contradictory.

Assemblies in hyde parks only — additional restriction by Constitutional Court

26. The Constitutional Court made an adverse reinterpretation of the role of specially designated areas for public events (so-called «hyde parks») regulated by regional authorities. The Court said that public events should be held principally in such areas, unless the event organizers prove that the event could not be held there for objective reasons. We consider that this is an additional restriction to the right of the organizers of assemblies to choose the place of the assembly. A draft law introducing such a restriction was discussed in the regional parliament of the Kirov region. It was not adopted but this was a dangerous precedent.

Bans on assemblies in certain places — partially removed

27. In its ruling of 4 June 2020, the Constitutional Court stated that regional restrictions should not be abstract in nature (i.e., generalized). The Court did not prohibit the introduction of regional bans but stated that such bans should not be absolute. The Court prohibited the introduction of absolute bans on gatherings near the schools, hospitals, military facilities, and places of worship. This ruling of the Constitutional Court has been narrowly interpreted by some of the regional parliaments to mean that a regional parliament cannot introduce absolute bans near the facilities specifically mentioned by the Constitutional Court but can introduce absolute bans near other facilities.

28. During the last year, Russian regional parliaments responded to the Russian Constitutional Сourt’s rulings. The bans on rallies in front of the public buildings have been removed in forty-three regions but have been retained in three regions. The bans on rallies in front of hospitals, schools, and military facilities have been removed in thirty-four regions but have been retained in twenty-six regions. The bans on the rallies at particular addresses have been removed in four regions but have been retained in four other regions. We welcome these positive changes to regional laws, but we believe reform should continue until all unreasonable bans have been eliminated.

Criminal responsibility for several protests — still takes place

29. The ruling of the Constitutional Court has not prevented application by the Russian courts of the criminal code concerning criminal liability for participation in the numerous non-approved assemblies (Article 212.1). For example, after the Constitutional Court’s decision on the Konstantin Kotov case, his sentence was reduced from four to one and a half years in prison (this sentence was completed in 2020.) Despite the reduced sentence, this conviction is still disproportionate to the «crime» committed and unfair. In December of 2020, Yulia Galiamina was also convicted under this article to a suspended sentence. Because of Russian legal requirements (under Article 212.1), Ms Galiamina was also forced to leave her posts as a university professor and municipal deputy.

Restrictions on pickets lines — case ongoing

30. The Constitutional Court is currently examining new amendments to the law that allowed lower courts to recognize a picket line or rotating solo demonstrations as an unauthorized public event. We think it is very important to adopt a decision qualifying the new legal restrictions as a violation of the right to freedom of assembly and freedom of expression.

Restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic

31. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic some temporary restrictions on the freedom of assembly have also been introduced in Russia.

Long-standing restrictions

32. The new restrictions were introduced in March 2020 and apply to date. By September 2020, these restrictions had been imposed in thirty-five Russian regions. In twenty-six regions (including Moscow and St. Petersburg), all public events are banned, regardless of the number of participants. Even solo protests are prohibited.

No alternative provided

33. The authorities did not facilitate freedom of expression by providing alternatives for assemblies during the pandemic. On the contrary, Russian authorities suppressed such alternatives. For example, in March 2020, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) banned the website devoted to the opposition campaign against amendments to the Constitution. In April 2020, mass media reported that users of maps apps had started «online assemblies» (they posted political comments that further reflected in the map). The application’s owner deleted these comments and the authorities failed to do anything about it.

Discriminative and non-proportional

34. The main problem with these measures is that they are applied in a discriminative and non-proportional way. These measures apply even when, according to the Russian authorities, the situation with the pandemic is stable. While authorities prohibit protests they authorise non-political mass assemblies (for example, sport’s, cultural, and advertising mass events).

35. Based on the above, we believe that these restrictions are applied to suppress political opposition rather than to protect citizens against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Police’s own non-compliance with anti-Covid restrictions

36. In addition, the law authorises the police to undertake mass arrests and detentions during non-authorised assemblies. This fact creates additional risks for the detained people to contract COVID-19.

37. There is extensive photo and video evidence publicly available, indicating that there was not enough space at police stations and detention facilities to hold all persons detained on 23 and 31 January 2021, and that many detainees were confined for hours to paddy wagons, in breach of health and infection control standards. No masks and gloves were provided by police; no social distancing was facilitated. The Public Verdict Foundation selected seven of the most egregious cases and filed a crime report citing these cases with the investigating authorities on 3 February 2021. Two months later, as of 31 March 2021, Public Verdict Foundation only know that its appeal has been forwarded to the Ministry of Interior’s Main Directorate for the city of Moscow, but not a single criminal case has been initiated against the law enforcement officials for violation of health and infection control regulations (Art. 236 of the Russian Criminal Code).

2. Freedom of assembly in practice

Problems with the approval

38. The available official statistics shows that Russian authorities still tend to refuse to authorise public assemblies.

39. Russian officials still do not publish their decisions regarding the authorisation of assemblies or the respective statistics. The only available set of federal statistics is the judicial one — concerning challenges of refusals. It does not show the whole picture, since not all the refusals are challenged in courts.

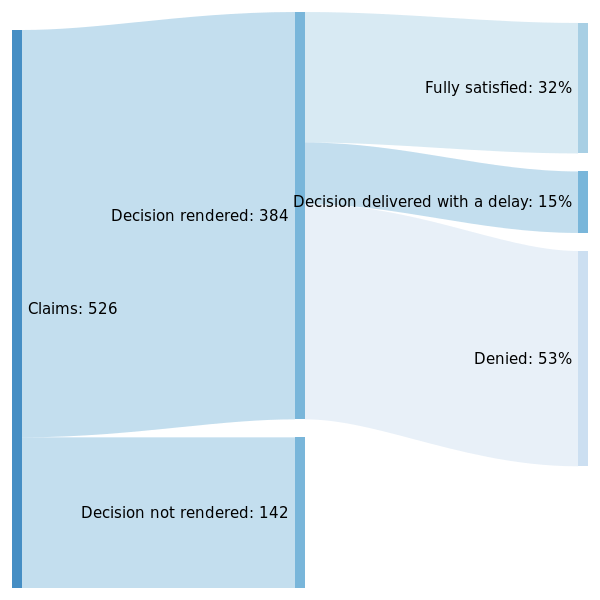

40. However, judicial statistics may demonstrate that:

- there are numerous claims by organisers, which means there were at least as many, if not more, refusals (526 in the first six months of 2020),

- in most cases courts either close cases on formal grounds, or reject claims;

- in cases in which courts satisfy claims, decisions often come too late (i.e., after the planned date of assemblies).

41. In addition, local statistics are sometimes available. The ombudsman in Saint-Petersburg published the statistics that showed similar unsatisfactory results:

- In cases where the number of participants was over 500 or where the venue was within the city limits, authorities approved only 15% out of 91 notifications in 2020, 40% out of 383 notifications in 2019.

- In cases where the number of participants was up to 500 or where the venue was out of the city limits, authorities approved 57% out of 317 in 2020, and 60% out of 1976 notifications in 2019.

Suppression of public events and detentions

42.Russian authorities still pursue a zero tolerance policy against “non-authorised” assemblies. Mass detentions have not stopped. On the contrary, the number of such detentions has increased dramatically.

43. In January and February 2021, a series of protests took place in no less than 185 cities throughout Russia and in the territory of the Crimean peninsula. These protests were accompanied by detentions on an unprecedented scale. More than 11,000 people in more than 125 cities were detained at the actions on 23 and 31 January, as well as on 2 February.

44. In 2020, OVD-Info was informed of 2,435 detentions in fifty-six regions of Russia. At least 799 (one-third) of these detentions occurred during solitary pickets. Most 2020 detentions were recorded in Moscow (1,322) and St. Petersburg (288). The largest numbers of detentions were recorded at events against the authorities (749) and against political repression (511 people).

45. Most detentions happened during the period from April till the end of 2020: 2,048 detentions were reported during 473 actions in fifty-three regions, mostly in Moscow (1,108) and St. Petersburg (189). Of these, at least 586 people were detained during solitary pickets. On 15 July in Moscow, at least 147 people were detained during a march against the new amendments to the Constitution.

46. This statistic does not take into account the post-factum and preventive detention of protesters. The practice of detaining protesters, not at the rallies themselves, but between them (on the street, at home, at work) was actively used in Khabarovsk, where protests have been regularly held since mid-July 2020. From 11 July to 1 December 2020, at least 64 people were detained at rallies in Khabarovsk, and almost twice as many, at least 121 people, were detained between rallies.

47. In addition, in Moscow, authorities began using face recognition technology to search for participants in unauthorized actions and bring them to administrative responsibility. In 2020-2021, these technologies had been introduced to track movements in order to ensure quarantine.

Violence, torture, and threats by the police

General

48. Cases of violence by police are still frequently reported during mass protests. The latest example is the violent suppression of peaceful opposition protests on 23 January and 31 January 2021.

49. During these protests, in many cities, the police detained unarmed and peaceful citizens using unjustified and excessive violence, and there were cases of targeted beatings both at the rallies and during detention. People were beaten on the head with batons, thrown onto the floor of a police van, kicked, and forced to sit and lie on the snow. The use of stun guns was reported.

50. Cases of beatings and torture inside police stations were also reported. In several Moscow precincts, detainees were taken to separate rooms and beaten (often with special tools) until they agreed to fingerprinting. Detainees were also denied telephone access. Similar cases were reported by detainees in St. Petersburg and Voronezh.

51. The detainees routinely faced pressure. They were threatened with physical and sexual violence, extension of the detention period, arrest, criminal proceedings, and various other punitive measurements.

Investigation of violence

52. After the above events, some individuals filed crime reports requesting investigation into their cases and prosecution of officials responsible for the illegal use of violence. However, investigative bodies tend to refuse considering such applications. Contrary to law, investigators do not register such applications as crime reports and do not perform a pre-investigation inquiry as prescribed by the Russian Criminal Procedure Code. In Exhibit No. 7 we provide information about the crime reports filed by the Committee Against Torture and the Public Veridict Foundation and the results of the examination of it.

Inhumane transportation conditions

53. The manner in which the detained protesters were transported in Moscow during January and February 2021 indicates that the law enforcement officials in charge of detention and transportation procedures do not prioritise compliance with prisoner (detainee) rights and transportation standards, resulting in massive and widespread violations affecting persons detained during protests. The detained people were transported over long distances in overcrowded vehicles without access to drinking water, food, or toilets. Some detainees spent 40 hours in prisoner transport vehicles and were denied even basic needs. See more details about the inhuman transportation conditions in Exhibit No. 8.

Violation of defense rights and other rights

54. After the detentions on 23 and 31 January many individuals were not authorised to see their counsels. They were also illegally deprived of their phones and pressed to submit to fingerprinting or photographing. See more details about these violations in Exhibits No. 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Administrative prosecution

55. After detentions, protesters are prosecuted in administrative court proceedings.

56. Official statistics show that:

- the number of administrative cases against protesters constantly increases dramatically. After the 23 January 2021 protest, 5,716 administrative cases were initiated in Moscow. In comparison, during the whole 2018 there were 1,039 cases initiated in Moscow, in 2019 — 3,275.

In St. Petersburg, the district courts received 1,659 cases under part 1 of article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation and 314 cases under Part 6.1 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation.

- the share of arrests has increased substantially as well: in the first two thousand administrative cases for violation of the procedure for holding a public event in Moscow, the courts imposed an arrest in 43% of cases and a fine in 56%; judges imposed arrest sentences 1,251 people, and fined 2,500 people.

In comparison, during 2019, when actions were also held in Moscow, accompanied by mass arrests, the share of arrests was only 4% of all indictments.

Criminal prosecution

57. Criminal prosecutions of protesters have continued in 2020 and in 2021: some of them continued from the past years, others just started in this period.

Continued collective prosecution

- During 2020, in progress was the so-called Ingushetian case: dozens of criminal cases against participants in mass protests against the revision of an administrative border between two regions of the Russian Federation, Ingushetia and Chechnya, in 2018 and 2019. Mostly, protesters from Ingushetia were charged with the use of violence against a law enforcement officer, or with organising an extremist community. Some of the protesters, who faced the accusation with the use of force, were sentenced to 3.5 years imprisonment, others are still in the process of prosecution (mostly those accused of organizing the use of violence or organizing an extremist community). Russian human rights organisations, e.g., HRC Memorial, stated that these criminal cases may be politically motivated. These issues were raised in applications to the ECHR, for instance in the application “Sautiyeva v. Russia” (application No. 8936/20).

- Another collective ongoing criminal case was the so-called Moscow case: a series of criminal cases brought from late July to late October 2019 after public events and social media publications protested the prohibition of independent candidates for elections to the Moscow City Duma.

New collective prosecution

- Vladikavkaz case: dozens of participants in protests in Vladikavkaz in April 2020 against mandatory self-isolation during the coronavirus pandemic and worsening economic conditions, were accused of, at least, hooliganism and violence against law enforcement officers. Unfortunately, there is a lack of detailed information about these cases in the public sphere. Human rights activists are afraid that such non-transparent prosecution could conceal human rights violations.

- Criminal cases against participants of the protests in Khabarovsk, which took place in the second half of 2020. The protest began as an expression of support for the ex-governor of the Khabarovsk region, Sergey Furgal, who had been criminally charged. Several people were charged with the use of violence against or insult to a law enforcement officer, as well as with repeated violation of the established procedure for the organization or holding public events. Nowadays, many of the cases have been closed, and in some cases the preliminary investigation ended with a refusal to initiate a criminal case. However, in different Russian cities, new criminal cases are still being brought against participants in public events in solidarity with the Khabarovsk protest. For example, in December 2020 in Novosibirsk, Darya Gorbyleva was charged with a use of violence against a police officer.

- The Palace case consisted of almost a hundred criminal cases following the unprecedented crackdown on peaceful protest in support of Russian opposition politician, Alexey Navalny, and against corruption in January and February 2021. Protesters all over Russia have been charged with a use of violence against police officers, blocking roads and pedestrian walkways, calls for mass riots, violation of sanitary and epidemiological rules, involvement of minors in illegal activities that pose a risk to their lives, and several other offences. In this case, protesters faced many new or dramatically amended criminal articles, on which law enforcement seems to be unclear and unpredictable (e.g. the violation of sanitary and epidemiological rules, as well as blocking of roads and pavements). By mid-April 2021, about 20 relevant court judgments had already been made.

58. In 2020, there were also cases of charging event organizers and participants with the repeated violation of the established procedure for the organization or holding of public events (Article 212.1 of the Russian Criminal Code). For instance, in December 2020 Russian politician, Yulia Galyamina, received a suspended sentence of two years. Earlier in 2020, activist Konstantin Kotov was serving a sentence of real imprisonment under the same article of the Criminal Code for a peaceful unauthorised protest. In the Kotov case, the Russian Constitutional Court re-examined the issue of the constitutionality of Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. The article was declared constitutional, but the Kotov case was sent for revision, as a result of which, the sentence was reduced from four years of imprisonment to a year and a half. Therefore, the legal problem was not resolved, and there are other similar cases in progress.

59. It is also important to mention, that there has not been a single criminal case against Russian officials concerning illegal obstruction of the holding of or participation in public events, or compulsion to take part in them (article 149 of the Russian Criminal Code). Moreover, we do not know of any suсh cases in the entire history of the existence of this criminal article. There are also many problems with investigation of police violence during public events (see section c( ii) above).

Other methods of pressure

60. A campaign to discredit the protests and intimidate participants, as well as potential participants, has grown. Authorities use various preventive measures: including threats of expulsion from university or dismissal from jobs. Protesters faced prosecution on charges with different offences, e.g., traffic violation and so on. Protesters were placed in psychiatric hospitals or in mandatory self-isolation. Protesters and their relatives may be visited by police officers: the formal reason is a “preventive talk” in order to prevent violations, however it is apparent that such visits are aimed at intimidation of protesters.

61. In preparation for rallies, police block central streets and metro stations, and restrict the operation of cafes and shops. City video surveillance and face recognition systems are used to identify protesters. All these measures take both chilling effects on exercising freedom of assembly: firstly, they intimidate and deter people from participating in the protest, secondly, they create an image of protest as something bad, dangerous and illegal. Moreover, often there are no effective remedies in the national legal system to challenge such interference.

Limitation of information about assemblies

62. The main problems in this sphere are detention and prosecution of journalists before, during, and after public events.

- The Russian Union of Journalists recorded over 200 violations of the rights of journalists who worked at protest rallies on 23 and 31 January and 2 February, in 40 regions of Russia. OVD-Info is aware of more than 150 arrests of journalists covering the protests. Some journalists were beaten by police officers with batons or stun guns, and some received head injuries.

- From the beginning of 2020 to 19 March, 2021, at least 71 cases were published by Russian courts under Article 20.2 of the Administrative Offence Code against journalists covering protests. These are cases from 16 regions (30 from the Khabarovsk region and 18 from Moscow). Out of 71 cases, 67 cases ended in a conviction. The maximum fine was 150,000 rubles (approximately 1,630 EUR on 13 April, 2021); the maximum sentence was 15 days.

63. Additionally, there are widespread practices of blocking and threat of blocking web-sites for publishing information about protests, as well as discrediting protest and freedom of assembly in the pro-state media.

Minors

64. Minors detained during the January and February 2021 protests were held for many hours in police vehicles while no formal records of their detention were made. The police failed to notify legal representatives when minors were brought to police stations. The minors were questioned without the parents. See more details in Exhibit 20.

3. Civil society’s initiatives and relations with the government

65. Russian human rights NGOs take various steps in order to improve the situation with respect to freedom of assembly in Russia. The NGOs sent individual complaints to national courts and to the ECHR as well as promoted legal and media campaigns against restrictive laws and bans. See the information about these initiatives in Exhibit 21.

66. However, only the Russian Government has the power and resources to fully implement the Lashmankin judgment, by repealing restrictive laws, draft laws, and controlling the reaction of police and other authorities to peaceful protests. Despite our efforts and suggestions, the Government is not communicating with us or taking real action aimed at the protection of the right to freedom of assembly in Russia.

67. Furthermore, human rights organisations dedicated to protecting the rights of protesters do not receive financial or other support from the Government; on the contrary, their efforts have been obstructed by governmental bodies. Memorial, the Committee against Torture, and the Public Verdict Foundation have been oficially labeled as “foreign agents”, which has resulted in additional restrictions and fines on these organizations.

4. Recommendations

68. In light of the above, we would like to propose to the Committee of Ministers the following measures:

- To adopt an interim resolution recognising that the case of Lashmankin has not been implemented by Russian authorities.

- To remind the authorities about the necessity of adopting the recommendations made by the Committee of Ministers in its previous decision.

- To propose to the authorities the adoption of the list of recommendations made by “Memorial” and OVD-Info in their previous submission to the Committee of Ministers on 20 April 2020.

- To remind the authorities that the most important reforms deriving from the case of Lashmankin (see Section 1(a) above) have still not been adopted by the authorities and to urge them to adopt these reforms.

- To condemn the new restrictive laws adopted by Russian authorities during the last year (see Section 1(b) above) and to state that the authorities must withdraw these laws.

- To welcome some positive drafts laws proposed by Russian deputies (see Section 1(c) above) and to encourage the authorities to adopt these drafts laws.

- To indicate that the practice of the Constitutional Court and regional laws must be more consistent and fully follow the findings of the ECHR in the Lashmankin case.

- To indicate that the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic must not be applied in a discriminative and non-proportional way.

- To condemn the mass arrests and prosecutions of participants in peaceful assemblies, perpetrated by the authorities during the last year.

- To propose that authorities create a working group at a federal level consisting of experts and civil society to discuss the reforms necessary for the implementation of the Lashmankin case.

- To decide to consider again the Lashmankin case during the next session of the Committee of Ministers together with the cases dealing with the related issues including “Tomov and others v. Russia”, “Fedotov v. Russia”, “Mikheyev v. Russia”, “Atyukov v. Russia”, “Zakharov and Varzhabetyan v. Russia”.

Скачать файл (.pdf)

Скачать файл (.pdf)