This article originally appeared in Meduza on Apr. 20, 2023

In 2011, after grossly falsified parliamentary elections triggered mass protests and a wave of political arrests in Russia, journalist Grigory Okhotin and software engineer Daniil Beilinson began publishing data about nationwide political persecutions. The project, dubbed «OVD-Info», is now one of Russia’s key civil-liberties advocacy organizations, providing both information and pro-bono legal services to people faced with real or potential political persecution. After more than a decade of observing protest dynamics in the country, Okhotin is convinced that depriving citizens of basic rights threatens not only the country’s well-being but also the safety and prosperity of the outside world. In an essay for Meduza, Okhotin reflects on more than two decades of Putin’s policies and explains how the consistent erosion of the Russians’ political rights ultimately resulted in the invasion of Russia’s closest neighbor, Ukraine.

Why the hegemony of executive power leads to persecution

At the turn of the millennium, and with the Second Chechen War in the backdrop, Vladimir Putin became the acting president of the Russian Federation. Today, more than two decades later, it is clear that, under the pretext of terrorism and other war-related external threats, Putin at the start of his presidency embarked on a quarter-century-long crusade against civil liberties in Russia.

Russia’s independent press closely covered the First Chechen war of 1994–1996, confronting the public and the government with a healthy stream of uncensored information. Journalists, human rights advocates, and civil activists organizing street protests all played important roles in ending that war. All this unfolded before a presidential election, and the Kremlin took to heart the lesson of just how inconvenient this civil activity could be.

In January 2000 (Putin’s first month in power), Russian law enforcement abducted Radio Liberty reporter Andrey Babitsky, signaling to the rest of the Russian media that things were about to change. Then, in June, TV executive and Media-Most holding company owner Vladimir Gusinsky was arrested and jailed in Moscow’s notorious Butyrskaya prison. After three days at the «Butyrka», he sold all of his media assets to Gazprom and fled the country. Gazprom’s acquisitions included NTV, an independent television channel that was key to covering the First Chechen War. As a result of this substantial media shift, the Russian news media’s coverage of the Second Chechen War largely adopted the state’s official perspective.

It wasn’t just the media that caused the Kremlin anxiety. However flawed, democratic competition was also a source of trouble. Moscow’s political and financial weakness, coupled with fairly open and competitive elections at all levels of government had by then resulted in the successful emergence of regional elites, paralleled by the creation of an industrial and finance lobby embodied by the oligarchs.

In the 1990s, these elites influenced not only the economy but also political life itself, including the outcomes of parliamentary and presidential elections. Then, in 2003, Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s arrest once again marked a sea change, whose essence was a tacit policy of Putin’s that the oligarchs would from now on take part in political projects only with the Kremlin’s permission and blessing. Regional elites, meanwhile, lost their influence as a result of reforms to elections for seats in the State Duma, which excluded single-mandate (winner-take-all) districts from parliamentary elections. The second factor compounding this was that regional governors ceased to be elected in 2004.

These changes cleared the way for the unobstructed growth of the federal government’s executive branch, headed by the president, and ultimately for that branch’s hegemony over all others.

The very first Putin-era parliamentary election robbed pro-democracy voters of representation. As a result, the two liberal parties that had been particularly vocal about the value of checks and balances — the Union of Right Forces and the Yabloko party — were simply booted from the Duma. The pro-Putin United Russia party, on the other hand, strengthened and has since continued to grow in both size and power. With time, the Putin regime gradually exerted more and more control over elections, always operating in its own interests.

This required legislative manipulations too: election campaigns in post-Soviet Russia never followed the same set of rules twice. Since 2009, lawmakers have introduced 266 changes to Russia’s election laws. Along with administrative methods for excluding the opposition from elections, direct falsifications have also become standard practice. Gradually, the opposition was shut out of public politics on the federal, regional, and municipal levels.

As the government’s legislative branch, the parliament ceased to be independent and became, functionally, a part of the executive branch tasked with transforming the president’s and the administration’s decisions into law. The contrast is plain to see — while only 11 percent of the legislation considered by the State Duma in the last pre-Putin convocation originated with the president’s administration, this proportion rose to nearly a third during the seventh convocation (2016–2021). Even more strikingly, close to 100 percent of the legislation that the administration had, in one way or another, placed in the hopper was ultimately adopted and enacted.

At the same time, deputies now consider and vote on legislation far more rapidly than before. While the Third Convocation State Duma passed 327 laws on an «expedited basis», the sixth convocation (2011–2016) saw 1,182 bills passed under the parliament’s expedited protocol.

The repressive legislation that, in effect, introduced military censorship immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 was passed in all readings and was signed into law by the president himself on a single day, March 4, 2022.

In April 2023, lawmakers ignored numerous violations of official protocol when adopting legislation that now permits the military to send draft summonses electronically, barring those summoned from leaving the country. (The violations include the substitution of a text passed in the second reading before the invasion with a different draft of the same bill.)

Bad omens in South Ossetia

The early 2000s confronted the Kremlin with new, post-Yeltsin challenges, particularly the emergence of a more radical anti-Kremlin opposition. On the one hand, Russia’s ruling elites immediately and broadly saw threats to their own power in foreign events like Georgia’s Rose Revolution in 2003, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004, and the 2005 Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan. On the other hand, the slow but steady eviction of the political competition from Russia’s parliament and other public offices led to the radicalization of Russia’s extra-parliamentary opposition — and to an awakening among Russia’s civil society.

The Kremlin’s response to these trends was to embark on a campaign against the «orange plague.» In 2004–2006, it devoted itself to suppressing Eduard Limonov’s National Bolshevik Party that favored direct-action campaigns like taking over state buildings (ministries, public offices, and the presidential administration building). Police arrested dozens of activists, and a court banned Limonov’s party in 2007 an «extremist organization.»

Around the same time, in 2006–2007, the police brutally suppressed the anti-Putin Dissident Marches, beating and arresting participants. The laws regulating and limiting grassroots organizations, meanwhile, grew more severe. The state made a concerted effort to expel international NGOs from the country, actively trying to discredit human rights groups in particular.

Like Putin’s first term, Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency (2008–2012) also began with a war. This time, it was the five-day-long conflict with Georgia that culminated in Russia’s recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states. After a ceasefire, multiple cases of human rights violations against ethnic Georgians emerged across South Ossetia. Petitioned by Georgia, the European Court of Human Rights found Russia responsible for the arbitrary arrests, violence, torture, and inhumane treatment of civilians that occurred in the region while under Russian control.

In Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov’s regime took root, growing in both power and violence. In 2009, the murder in Chechnya of human rights icon and Memorial board member Natalia Estemirova made clear that Memorial itself and its advocacy work were no longer welcome in Kadyrov’s realm. The message could not have been clearer, given the earlier murder of Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist at the newspaper Novaya Gazeta who had covered events in Chechnya.

The practices then becoming entrenched in Chechnya and across the North Caucasus were still far from becoming evident in Russia’s wider domestic politics. The Medvedev presidency saw improved relations with the U.S. At home, the new president’s liberal rhetoric lessened social tensions. Cosmetic reforms created an appearance of progress, and civil society tried to make do with its remaining political instruments, but Medvedev never repealed or dismantled a single element of Russia’s existing authoritarian infrastructure. At the end of this «breather», the Kremlin «castled», and Putin returned to presidency, despite mass protests against his return and the fraudulent Duma election.

The Kremlin met those protests by imitating political reforms (bringing back, for example, direct gubernatorial elections), but this was nothing more than a democratic publicity stunt calculated to help the regime stay in power despite the waning popularity of United Russia and Putin himself. In reality, behind the scenes, the opposite of democratization was underway, as the regime prepared to trade localized persecutions for systemic repressive measures.

The repressive watershed

The protests of 2011–2012 led to mass arrests and prosecutions. In the Bolotnaya Square case alone, dozens of people were sentenced to real prison terms. Once Putin was back the Kremlin, the State Duma passed a series of new repressive laws that hardened the state’s control over public demonstrations, «foreign agents», «undesirable organizations», «gay propaganda», and lots more. It was around this time that the opposition sarcastically dubbed the State Duma a «mad printer».

Something or someone in the state had clearly gone berserk.

Putin’s third presidential term became a watershed moment in the rise of political repressions in contemporary Russia. Until then, repressive practices were a centrally controlled precision instrument for keeping the opposition in check. After new laws limiting civil liberties came into effect, however, repressions acquired a new, institutional character: instead of being used against specific personas non grata on a case-by-case basis, they became the state’s systematic response to certain types of citizen behavior. At the same time, control over repressions shifted from the higher echelons of power to numerous law-enforcement agencies and structures, penetrating deeper into society.

The 2014 annexation of Crimea and the start of combat operations in the Donbas resulted in another wave of pressure on civil liberties. Free speech came under attack in the form of blocking a whole class of independent media, coupled with the dismissal of the entire editorial staff at Russia’s most popular independent news outlet, Lenta.ru. Antiwar protests led to further mass arrests. Russia’s pro-Ukrainian opposition faced criminal prosecution. Laws once again became more restrictive. In 2015, opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was assassinated.

Repressions thus became a «technology» that Russia could now export to the Ukrainian territories under its control. In Crimea and the newfangled Donetsk and Luhansk «republics», local officials began to adopt the Russian law enforcement’s «best practices»: hundreds of Ukrainians went to prison for political reasons; people vanished; torture and violence became a recurrent reality. Grassroots organizations and the freedoms of speech and conscience they promoted were now faced with systematic pressures.

Institutionalized repressive practices spread to Ukraine through the newly arrived Russian bureaucrats and law-enforcement workers, almost as soon as those practices took root in Russia. Meanwhile, the Russian military had already grown accustomed to extrajudicial violence (with abductions, torture, and extrajudicial executions), having «purged» and «filtered» the Chechen and South Ossetian populations without rebuke or punishment at home.

While this fact had been ignored and forgotten in Russia, the military stood ready to repeat what it had learned.

From ‘containment’ to liquidating the opposition

As Putin’s abrupt popularity spike after the annexation of Crimea fizzled out in 2016–2019, political repressions gained further momentum. This was evident not only in the number of Russia’s politically motivated criminal prosecutions, but also in their broadening scope, which expanded from the socio-political arena to the cultural and the academic spheres.

Even at this stage, the repressive measures were still aimed at containing protests and keeping the expression of civil liberties within certain limits that the regime perceived to be safe for itself. Some minimal scope for the development of civil society still remained. But in 2019, after Moscow witnessed new mass protests (these connected to the exclusion of opposition candidates from City Duma elections), another major shift occurred in the regime’s repressive approach.

The coronavirus pandemic permitted the authorities to ban practically all forms of public assembly. Constitutional amendments that enable Putin to remain in power until 2036 were passed under highly dubious circumstances, including Russia’s first-ever use of electronic voting. This was followed by the poisoning of Alexey Navalny; mass protests and arrests in response to Navalny’s arrest; the ousting of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation and of Open Russia; a massive campaign against NGOs, the free media, and other «foreign agents»; and finally the liquidation of Memorial, Russia’s oldest human rights group.

All of this marked a major transition from merely containing the activities of civil society to a policy of outright eradication.

The persecutions that gained momentum some 12–18 months prior to the invasion of Ukraine had already weakened Russia’s opposition and its civil life by the time the war began, but as soon as it launched the invasion, the Kremlin unleashed yet another repressive wave at home, targeting the war’s critics. Police arrested some 20,000 people just for antiwar statements; thousands faced liability for antiwar social media posts; hundreds of activists and politicians were arrested or jailed; and the federal censor blocked tens of thousands of websites.

This and the rise of militarized ideology suggests that Putin’s authoritarianism is once again transitioning, this time into a principally new form. Although it shouldn’t be mistaken for totalitarianism, the unbridled violence of this regime, already obvious from frontline news, is bound to show its terrible «true colors» within Russia’s domestic space.

In this context, the new conscription legislation, which can potentially corral hundreds of thousands of Russians into going to war, may not be the culmination of the regime’s violence against its own people.

The fruits of Putinism

The pattern that can be extracted from the two decades of Putinism we just surveyed is a pattern of the consistent and systemic curtailing of civil liberties. What has this policy achieved? Behold a list of its accomplishments:

- The destruction of democratic institutions (including elections for all levels of public office), of parliamentary governance, and of the division of power within the state. As of today, voters have practically no say in the workings of Russia’s political system. Power is concentrated in one set of hands; the systems of checks and balances are in shambles; the feedback loop between the state and society has degraded.

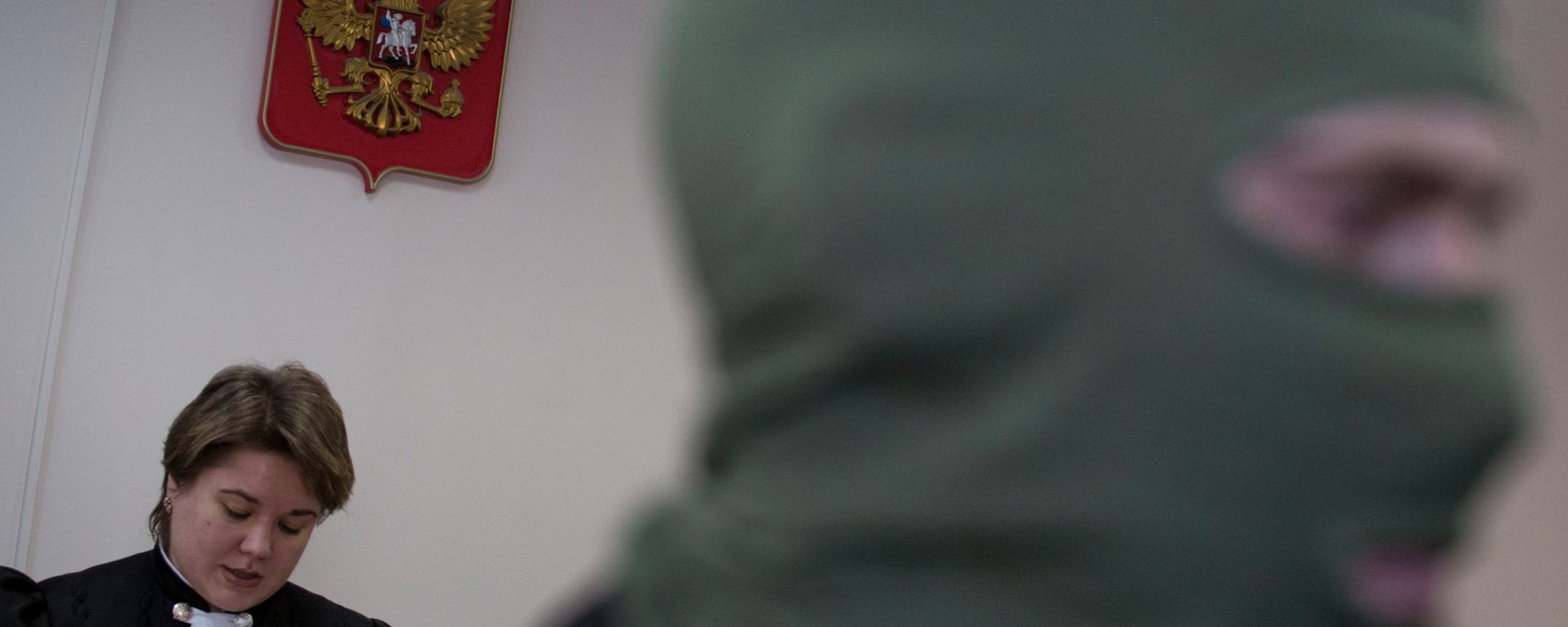

- The destruction of the legal system, noncompliance with supranational courts and their decisions, the erosion of parity in court, and the loss of judiciary independence. As a result, society itself has been completely stripped of legal agency.

- The monopolization of information. Directly or through state-owned corporations, the state controls the overwhelming majority of the media. Persecution, censorship, and harsh legislation have all but suffocated Russia’s independent media.

- The erosion of the institutes of civil society by means of prosecuting activists, stigmatizing advocacy for human rights and civil liberties as the work of «foreign agents», closing down socially significant organizations, and curtailing the rights to peaceful assembly and free association, such that people fear participating in any form of public life.

- The opposition’s physical destruction, including either the full dissolution or prohibition of all the significant independent socio-political structures. All of Russia’s opposition leaders of national magnitude are either dead, imprisoned, or forced to live abroad.

Taken together, what these changes amount to is a total destruction of Russian society’s political agency. In these conditions, the narrow circle of individuals who unleashed the aggressive war against Ukraine faced minimal risks of accountability for their decision.

This destruction of agency isn’t equal to the destruction of Russia’s civil society as such. That civil society has changed, adapted, and survived. The outlawed and dissolved NGOs and political organizations have continued their work, alongside hundreds of new initiatives launched since the start of the full-scale invasion, to help both Ukrainians (by paying, for example, for their travel from Russia to Europe) and Russians (with things like avoiding prosecution or the draft). Most of the blocked media have found novel ways for continuing their work, with new media projects joining them in providing uncensored coverage of Russia’s aggressive war. Compulsory mass emigration in the face of repression has only made Russia’s civil society stronger since its work can now go on in safer settings.

Hundreds of thousands of people keep donating to grassroots organizations despite the risks; tens of thousands actively support these organizations with volunteer work. In response to the risk of prosecution, protest has become individual, but current data on detentions and criminal prosecutions show that this solitary protest is not as isolated as it might sound.

It is both necessary and possible to resist Russia’s military aggression, but this isn’t enough to stop the present authoritarian regime in Russia from posing a threat to peace and prosperity. The real answer to this threat is what Ukrainian human rights advocate Oleksandra Matviichuk said in her 2022 Nobel Lecture, when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties:

This is not a war between two states, it is a war of two systems: authoritarianism and democracy.

We have to start reforming the international system to protect people from wars and authoritarian regimes. We need effective guarantees of security and respect for human rights for citizens of all states regardless of their participation in military alliances, military capability, or economic power. This new system should have human rights at its core.

Grigory Okhotin for Meduza

Adapted for Meduza in English by Anna Razumnaya