Publication date: 10.04.2023

The report highlights the persecution of media workers and the media themselves; criminalisation of anti-war speeches; the use of military propaganda and hate speech; use of censorship and shutdown of the Internet; and the use of surveillance, on the Internet included.

Submitting organisations:

Justice for Journalists Foundation (JFJ) is a British non-governmental organisation (Registered Charity 1 201 812) created in 2018. JFJ has been monitoring, analysing, and publicising attacks against media workers that took place since 2017 in 12 post-Soviet states, including Russia. The monitoring is based on data collected by content analysis of open sources. In addition, expert interviews with media workers are used to monitor cases that have not been publicly reported. All information is verified using at least three independent sources. JFJ also funds journalistic investigations into violent crimes against media workers and helps professional and citizen journalists to mitigate their risks.

OVD-Info — an independent human rights media project aimed at monitoring cases of political persecution and violations of basic human rights in Russia and providing legal assistance to their victims. OVD-Info operates a 24-hour federal hotline to collect information on all types of political persecution, does their media coverage, offers free legal assistance and education, researches different types of political persecution in Russia and engages in international advocacy.

Access Now is an international organisation that works to defend and extend the digital rights of individuals and communities at risk around the world. Through representation worldwide, Access Now provides thought leadership and policy recommendations to the public and private sectors to ensure the continued openness of the internet and the protection of fundamental rights. By combining direct technical support, comprehensive policy engagement, global advocacy, grassroots grantmaking, legal interventions, and convenings such as RightsCon, we fight for human rights in the digital age. As an ECOSOC accredited organisation, Access Now routinely engages with the United Nations (UN) in support of our mission to extend and defend human rights in the digital age.

ARTICLE 19 is an international think–do organisation that propels the freedom of expression movement locally and globally to ensure all people realise the power of their voices. ARTICLE 19 combines research, campaigning, and cutting-edge legal analysis to strengthen people’s right to free expression and access to information.

Follow-up from the Russian Federation’s third cycle

1. The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is an important UN mechanism aimed at addressing human rights issues across the globe. The submitting organisations welcome the opportunity to contribute to Russia’s fourth review cycle. This submission examines the freedom of expression and the persecution of media workers and media outlets; criminalisation of speech and assembly and association; the use of war propaganda and incitement of hatred and violence; the use internet shutdowns and website blockings; and the use of surveillance in violation of Russia’s obligations enshrined in Articles 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, and 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

2. During the third UPR cycle, Russia received 317 recommendations, of which 191 accepted, 92 noted, and 34 partially accepted. None of the recommendations addressed digital rights specifically. Russia supported 5 recommendations on freedom of expression and 1 recommendation on freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

3. Relevant recommendations on freedom of expression from previous round of UPR include 147.194, 147.172, 147.127, 147.159, 147.169, 147.150, 147.161, 147.188, 147.163, 147.172 — 147.174, 147.170, 147.166, 147.171, 147.65, 147.54, 147.61 147.167, 147.153.

Russia’s international and domestic human rights obligations

4. Russia has signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), among other international human rights instruments.

5. Russia’s Constitution contains several provisions which affirm the right to privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of peaceful assembly and association on and offline throughout the country.

Freedom of expression and the persecution of media workers and media outlets

6. Since Russia’s last UPR review, the country lost 7 positions in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index and currently ranks 155 out of 180 countries as opposed to 148 out of 180. Freedom House’s Internet Freedom Score for Russia remains in the category «not free», moving from 33 to 23.

7. In 2018-2022, JFJ documented 6413 cases of persecution of media workers and media outlets. 425 of them were physical threats, 590 — non-physical attacks, including cyber-attacks, intimidation and harassment, and in 5398 instances, judicial and economic means were used to exert pressure, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, forced bankruptcy proceedings, and enforced disappearances. In the overwhelming majority of cases (about 88%), the perpetrators were representatives of the authorities, including law enforcement, special services, and high-level leadership. The main targets were media outlets critical of the government, independent media workers, and their relatives and loved ones.

8. In 2023, as of March 27, 2023, JFJ documented at least 161 cases of media persecution: 5 physical attacks and threats to life, 7 non-physical attacks, and 149 instances of judicial and economic attacks.

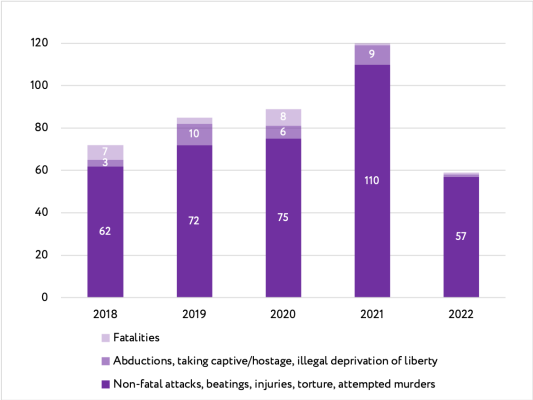

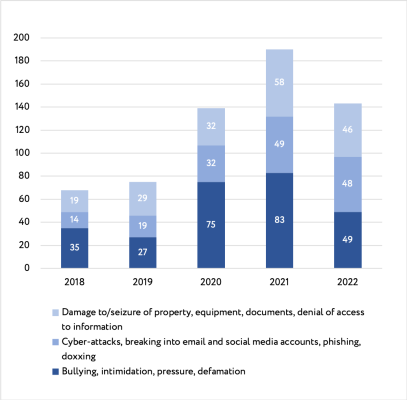

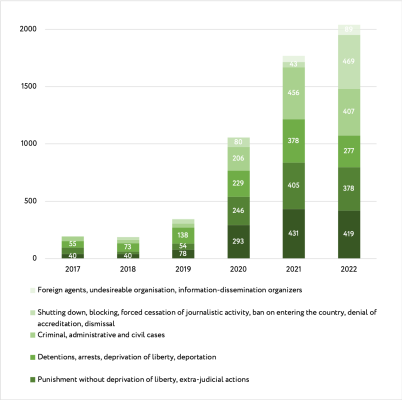

9. The graphs below prepared based on the JFJ’s data illustrate the consistent distribution of cases over the years and the most widely used types of persecution within each category:

а) Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

b) Non-physical attacks and/or cyber-attacks and threats

c) Use of judicial and economic measures

Continued harassment and physical attacks and threats

10. Over the course of the years under review, JFJ documented dozens of physical attacks and threats against Russian media workers, including the shooting of Kirill Radchenko, Alexandr Rastorguyev, and Orkhan Dzhemal in July 2018, the stabbing of Imran Aliyev in France in January 2020, and the suicide of Irina Slavina in October 2020 after she faced harassment from authorities. Aleksandr Tolmachev, who spent nearly nine years in prison on a reportedly false charge of extortion, also died suddenly in November 2020 after not receiving proper medical care.

11. At least 16 attempted murders and one case where an attempted murder was being planned but not carried out have been documented. These happened in Russia and abroad, particularly in Sweden and Finland, where two critical bloggers from the Chechen Republic were targeted.

12. Media workers in Russia have been abducted, tortured, and subjected to violence. Examples include the disappearance of Leonid Makhinya in 2018, the abductions of Salman Tepsurkaev and Sergey Plotnikov in 2020, the attack on SOTA journalist Pyotr Ivanov and on blogger Karim Yamadaev in 2021, among others. Later, a Chechen opposition channel reported that Salman Tepsurkaev was killed. On 5 September 2020, Chechen law enforcement authorities allegedly abducted Mr. Tepsurkaev, a moderator of the 1ADAT Telegram channel known for its criticism of the Chechen authorities and dissemination of information on human rights violations committed in Chechnya. After several days of sexual and physical torture, some of which was recorded on video subsequently publicized, on 15 September 2020, the kidnappers reportedly killed Mr. Tepsurkaev. According to the reports, he was tied up, a grenade was put in his mouth, and he was blown up from a distance.

13. The doors of media workers’ homes have been vandalised with letters "V" and "Z", symbolising support for the invasion of Ukraine, as well as with insults and threats in retaliation for the war coverage. JFJ documented at least 9 such cases.

14. Moreover, public officials, in particular from the Chechen Republic, regularly threaten media workers in public statements and social media posts. In the most recent and representative case, on 23 January 2022, the head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov wrote in his Telegram channel that the journalist Elena Milashina, who covers the human rights situation in the Chechen Republic, is a "terrorist" because of her critical publications. He encouraged the law enforcement to arrest her as a "terrorist supporter" and implied that terrorists have traditionally been liquidated. Elena Milashina and her colleagues from Novaya Gazeta were repeatedly threatened and attacked in the past.

15. Journalists have also been frequently assaulted and beaten, often having their equipment seized or damaged, during their work. Since 2017, the level of cruelty of such attacks has increased. The perpetrators included both state actors (such as law enforcement officers and public officials) and non-state actors (including from pro-government political groups, such as the National Liberation Movement ("NOD") and the South East Radical Block ("SERB")), as well as unidentified persons. The overwhelming majority of killings and physical attacks against media workers in Russia are not effectively investigated.

16. In April 2022 Dmitry Muratov, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning Russian journalist, was attacked on a train heading from Moscow to Samara. Muratov is the editor-in-chief of the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, an independent media outlet critical of the nation’s government. The attack that left him with impaired vision had not been investigated. United States officials alleged that. Russian intelligence was behind the attack.

17. In 2017-2021, charges were brought against ten Crimean Tatar citizen journalists from the Crimean Solidarity initiative for their alleged participation in Hizb ut-Tahrir (the Supreme Court of Russia banned it as a terrorist organisation in February 2003; however, it is legal in Ukraine and the majority of other countries) and preparing a forcible seizure of power. As a result, nine of them were imprisoned and given 14-19-year sentences. Currently, a total of 14 journalists are currently behind bars in the Russian Federation and the occupied Crimea.

Continued forced emigration and pressure on families

18. At least four more journalists publicly announced that they had left Russia as a result of the repression and pressure from the authorities: DOXA editors Armen Aramyan, Natalya Tyshkevich, Alla Gutnikova, sentenced on 12 April 2022 to two years of correctional labor, and a blogger Insa Lander, who was under house arrest facing terrorism charges when he fled the country. Many more media workers are leaving the country without making prior announcements to avoid further risks.

19. Hundreds of media workers who previously left the country also remain abroad due to the ongoing risks. Russian authorities continue harassing their relatives and loved ones living in Russia through house searches, interrogations, and other means — at least 10 such cases became public.

20. The relatives of Isabella Evloeva, the editor-in-chief of the independent media outlet Fortanga, are under particular pressure from the authorities through home searches, interrogations, and other types of intimidation and harassment. Ms. Evloeva had to leave Russia for Europe several years ago due to the risk of criminal prosecution for covering the protests in Ingushetia in 2019. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she has been writing about it in Fortanga and her personal blog. As a result, the Russian authorities brought three criminal cases against her under Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code (CC) ("public dissemination of knowingly false information about the use of the armed forces"). The law enforcement officers have also reportedly communicated to her that they will "have to" harass her parents until she stops writing.

Use of judicial and economic pressure: criminal and other forms of legal prosecution

21. The use of judicial and economic pressure further intensified and included the following trends:

а) Сontinued penalisation of media workers: in 2019 — 2023, the Russian government continued subjecting journalists to criminal prosecution. Some of the high-profile cases include:

- In June 2019, the Russian authorities brought wrongful drug-related charges against investigative journalist Ivan Golunov, but thanks to the unprecedented public support and protests, he was released and the case against him was closed. The police officers involved were later charged and convicted for planting the drugs on Golunov.

- On 6 July 2020, Russia’s Second Western District Military Court convicted journalist Svetlana Prokopyeva under criminal charges for "extremism" and "justification of terrorism" for discussing the reasons behind Mikhail Zhlobitsky’s terrorist attack on her program and column, which led to a fine of 500 thousand rubles (equivalent of 6,400 USD).

- On 6 September 2022, a Russian court sentenced Ivan Safronov, a former Kommersant and Vedomosti defense reporter, to 22 years of prison under Article 275 of CC ("high treason"). During the investigation (more than 2 years), he has reportedly not been allowed to receive a single visit or phone call from his family, has been denied correspondence for several months, and has been repeatedly prevented from communicating with his lawyers.

- In March 2023, Russian authorities arrested Evan Gershkovich, a US citizen and a reporter working for The Wall Street Journal, while on a reporting trip in Russia. He was accused of spying, making him the first journalist detained in Russia on espionage charges since the Cold War. The Journal vehemently denies the allegations. President Biden and news organisations around the world have joined the Journal in calling for Mr. Gershkovich’s immediate release.

- In total, since the adoption of the relevant laws in March 2022, the Russian authorities opened 38 criminal cases against media workers under Article 207.3 ("fake news about Russian army") and seven — under Article 280.3 ("public discrediting of the Russian army") of the CC. At least 90 administrative cases against media workers and outlets were initiated under Article 20.3.3 and three under Article 20.3.4 of the Code of Administrative Offences (CAO), which can also lead to further prosecution under Article 280.3 and Article 284.2 ("calls for sanctions against Russia, its citizens or legal entities") of the CC.

- On 15 February 2023, the Leninsky District Court in Barnaul convicted Maria Ponomarenko of disseminating false information about the Russian armed forces (Article 207.3) for publishing information about the Russian bombing of a theater in Ukrainian city Mariupol and sentenced her to six years in prison, along with a five-year ban on journalistic activities.

- On 7 March 2023, the Timiryazevsky District Court of Moscow convicted Dmitry Ivanov, a blogger who ran the Telegram channel "Protest MSU" under Article 207.3 for publishing posts about the Russian army’s war crimes in Ukraine, and sentenced him to eight and a half years in prison, along with a four-year ban on administering websites.

- On 6 March 2023, the court in Kemerovo sentenced journalist Andrey Novashov to eight months of correctional labor under Article 207.3, along with a one-year ban on journalistic activities, for an anti-war post on social media.

b) Russian authorities continued to widely use house searches, seizure of electronic devices, and interrogations — JFJ recorded 75, 45, and 30 cases, respectively, from January 2022 until March 2023. The authorities issued country-wide or international search warrants for at least 17 media workers.

c) FJF documented that Russian authorities have used at least 20 administrative fines for different offenses to financially undermine media workers and outlets.

d) On 15 August 2022, the Russian government-initiated bankruptcy proceedings against Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty LLC at the request of the tax inspectorate. Prior to that, since the beginning of 2021, the authorities drew up thousands of protocols against the media for not marking its materials as produced by a "foreign agent" and refusing to delete publications about the war in Ukraine. The government fined Radio Free Europe a total of 1 bln 64.3 mln RUB (18.8 mln USD). In February 2023, a Moscow court declared the media bankrupt for refusal to pay the "foreign agent" fines.

e) On February 24, Roskomnadzor informed the media that they should only use official information about the armed conflict in Ukraine and demanded that the media delete any publications where the words ”war” or ”invasion” are used instead of ”a military operation”, and reports on shelling cities or claiming Russian personnel losses, otherwise threatening to block and fine them (up to ~78 200 USD). As a result, the Russian government blocked at least 316 independent media outlets and canceled the Nobel Prize winner Novaya Gazeta and its Novaya Rasskaz-Gazeta magazine media registration. Most independent media outlets have suspended or stopped their operation in Russia.

f) The Moscow City Prosecutor has requested the Moscow City Court to dissolve the Journalists’ and Media Workers’ Union, citing ”grave violations of the law”. The court satisfied the request to dissolve the Union. The Tagansky District Court of Moscow also fined the Union for discrediting the army.

g) The Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued adding dozens of foreign media workers from the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and other countries, to the ”stop lists”. The total number of foreign media workers officially banned from entering Russia is at least 146.

Criminalisation of speech, assembly, and associations

Сriminalisation of information about protests and attacks on journalists covering such events

22. After the return of Alexei Navalny to Russia, large-scale protests took place in the country. The Russian Trade Union of Journalists recorded more than 200 violations of the rights of journalists who worked at those protest actions. Some journalists were severely beaten by police officers, including with batons or electric shockers. During anti-war protests in Russia in 2022, the Russian authorities detained at least 130 journalists.

23. Since 2018, authors of social media posts can be held accountable for organizing unauthorised assemblies, leading to self-censorship and difficulty in informing potential participants. Even a repost or publication calling for a rally can lead to liability, and authorities have used social media statements in case materials against some defendants in cases of repeated violations of the procedure for holding public events (Article 212.1 of the СС).

24. Amendments to the law ”On Information” in December 2020 required social network owners to monitor and restrict access to banned information, leading to intensified censorship during mass protests in January 2021. Prosecutor General and Roskomnadzor warned social network owners that they would be fined for dissemination of information about protests. Many social networks blocked pages and accounts with banned information about the protests, while Roskomnadzor put pressure on the media seeking to remove news about upcoming events.

25. In April 2021, a new wave of protests broke out. Roskomnadzor continued to demand the removal of Navalny’s team’s content from YouTube, and in July, demanded the removal of channels belonging to his associates. The government fined social network VKontakte a total of 3 million rubles (38,5 thousand USD) for links to YouTube. Google, Facebook, and Twitter received 16 protocols and fines of tens of millions of rubles for refusing to remove banned content and calls to attend unauthorised rallies in Russia. Individual sites, including the student magazine DOXA and the Communist Party, also faced blocks or removal of content due to "calls" to participate in protests. Among other civil society organisations, the government also blocked OVD-Info’s website for an article about protests in support of the opposition figure Alexei Navalny.

Stigmatizing labels

26. Since 2014, Russian authorities have been using the so-called "foreign agents" law as a tool to silence dissent, imposing heavy burdens upon civil society organisations and media that receive foreign funding and engage in what the government deems ”political activities”, and stigmatising them by labeling them as ”foreign agents.“

27. In 2022, the government expanded the criterion for designation as a ”foreign agent” from foreign funding to ill-defined ”foreign influence”. Starting in 2023, all "foreign agents" are obliged to post an additional public report online or to provide it to the media. The amount of information that needs to be reflected in the report will be determined by the authorised body every six months. The government has also increased penalties for non-compliance.

28. In 2022, 181 individuals and organisations were added to the list of ”foreign agents”. In 2021 the number was 101.

29. Since the start of Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian NGOs, journalists, and activists have been labeled with this status for their anti-war position and for ”gathering information on military and military-technical activities” on a highly discretionary basis. 156 out of 216 individuals and organisations added to the ”foreign agents” registries from February 24, 2022 to February 24, 2023, had publicly condemned the war.

30. Some of the recent notable ”foreign agents” cases include:

- In September 2021, Russia declared OVD-Info a ”foreign agent”. In December 2021, a Russian court liquidated the Nobel Peace Prize winning organisation Memorial for not labeling their social media posts as produced by ”foreign agents”.

- On December 23, 2022, the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation added ”Roskomsvoboda”, a prominent Russian digital rights NGO and the Feminist Anti-War Resistance movement, a grass-root initiative formed by a group of feminist activists as a response to Russia’s invasion to Ukraine, to a list of „foreign agents.“

- On January 23, 2023, the government added the Digital Rights Development Foundation. On March 31, 2023, the government also designated Teplitsa of Social Technologies.

- Five more NGOs and non-registered associations, representing the rights and interests of LGBTQ communities in Russia, appeared on the list in 2022. T9 NSK, a project for transgender people and their close ones, Sports LGBT Community, Samara Public Organisation LGBT Irida, Trans Initiative Group T-Action and Moscow Community Center for LGBT initiatives were among them. In 2023, the government also added the Alliance of Heterosexuals and LGBT for Equality to the registry.

31. Currently, 61 media organisations and 129 journalists are in the "foreign agent" registries.

32. In addition to the ”foreign agents” laws, Russia uses the "undesirable organisations" law that gives prosecutors the power to extrajudicially declare foreign and international organisations that allegedly undermine Russia’s security, defense, or constitutional order as "undesirable", shut them down, and criminally prosecute organisations and individuals who participate in activities of such organisations.

33. Seven media-related organisations are currently designated as ”undesirable organisations”.

- After the start of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine, 3 largest independent investigative media (Bellingcat, Important Stories, The Insider) were recognised as ”undesirable”.

- On 26 January 2023, Russia’s Prosecutor General designated Meduza, a prominent Russian independent media in exile, as an "undesirable organisation". From now on, Russian citizens who share hyperlinks to Meduza’s materials or donate to the outlet can face immediate fines and felony charges.

34. Currently, 61 media organisations and 129 journalists are in the "foreign agent" registries.

35. The Russian government also blocks the websites of ”foreign agents” and ”undesirable organisations” and pressures social media platforms to remove their resources. In addition, all media outlets are forced to comply with the labeling requirements under threats of large fines.

36. Moreover, in 2022, the government significantly expanded the administrative and criminal liability for non-compliance with "foreign agent" laws. The administrative article includes more reasons for a fine now, and the repeated violation is a criminal case. Since 1 January 2023, there is already one criminal case opened under amended Article 330.1 of the CC and at least 27 fines under administrative provision (Article 19.34 of the CAO).

37. In addition, in 2022 Russia expanded its anti-LGBTQ legislation, prohibiting "gay propaganda" not only among children as it was before, but among people of all ages. Sharing positive and even neutral information about LGBTQ people, and publicly displaying non-heterosexual orientations can lead to heavy fines. The new law will most likely be used to shutter NGOs representing the rights and interests of LGBTQ community, block their websites, and censor LGBTQ activists on social media platforms. The law also means de facto censorship in the field of artistic expression, since films or other visual arts with LGBTQ themes are now prohibited.

38. In Russia, the authorities also use anti-extremism laws to criminalise and censor undesirable media outlets, organisations, and platforms. The Russian government has also declared Facebook and Instagram ”extremist” and blocked the platforms. The government has issued at least one official warning for the use of Instagram.

Laws on ”fake news” and ”discrediting”

39. After the Russian government introduced punishment for the dissemination of fake news in 2020, the law enforcement has been actively implementing this legislation. The number of administrative cases had increased ten times between March and June 2020 (157 cases). The government has collected at least 1.4 million RUB (18 039 USD) in fines. During the first two months of the operation of Article 207.1 of the CC (April–May 2020), the government opened criminal cases under it ”more often than every two days, including weekends and holidays”. In 2020, according to the data provided by the Supreme Court, five people were convicted for disseminating misinformation about the pandemic, including journalist Alexander Pichugin. This provision on criminal liability for fakes has become a convenient tool for reprisals against those who publicly criticise authorities during the pandemic.

40. Another regulation adopted in March 2019, introduced amendments to the Article 20.1 of CAO regarding ”disrespect of authorities”. The violation of this law involves content blocking and administrative punishment. The restrictions enshrined in the disrespect of authority law are the harshest and broadest of all Russian restrictions relating to criticism. They are based on vague notions, protect a range of institutions related to state power and attributes in general, and provide the authorities with an easy, extrajudicial means to block access to content. Moreover, although the president is not explicitly listed in this law, 78% of administrative cases under this provision included online criticism of Vladimir Putin.

41. Within 10 days after the start of the war, the Russian government adopted new articles of the CC and CAO, which came into force all in one day. Article 20.3.3 of the CAO makes public discrediting of the use of the military punishable with up to 520 USD and 5 200 USD for natural and legal persons, respectively. The article was further amended to cover the activities of other state bodies abroad and activities of ”volunteer associations”, including private military groups such as the Wagner group. The repeated violation is punishable under CC Article 280.3.

42. In practice, the law is interpreted broadly and in an unpredictable manner, outlawing any expression of anti-war sentiments. People were found guilty under this law for displaying anti-war or pro-Ukraine signs or elements of clothing; taking part in anti-war rallies or their "silent support"; posting photos, comments, or even liking anti-war posts on social media; sharing information about the death of civilians, destruction of civilian objects, and claims of war crimes of Russian army; expressing opposition to war in conversations; or opposing the state-promoted pro-war symbols.

43. The Russian authorities brought more than 6290 cases under Article 20.3.3 of the CAO as of March 2023, according to the court data. The total sum of fines imposed is more than 100,000,000 RUB (1,294,000 USD).

44. Another major legislative novelty is Article 207.3 of the CC, which is punishing ”deliberately false information about the use of Russian armed forces and activities of other state bodies and private military groups.” While the offense of ”discrediting” punishes value judgments and expression of opinion, Article 207.3 allows to prosecute factual statements with up to 15 years of imprisonment as a punishment. There are now at least 146 people criminally prosecuted under this provision, and 59 — under ”discrediting” criminal article.

45. The longest sentences are — 8,5 years to opposition politician Ilya Yashin and leader of a Moscow State University student protest organisation Dmitry Ivanov, 7 years to independent municipal deputy Alexey Gorinov, and 6 years to independent journalist Maria Ponomarenko. Courts are now considering the cases under Article 207.3 against people who left the country in absentia (a very rare occurrence in Russia).

War Propaganda and Incitement of Hatred and Violence

46. Since the start of large-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities started to broadcast propaganda of war aiming to convince the society that the invasion was a ”forced response to an imminent threat from Ukraine” and actions of Russian armed forces are in full compliance with international law. Rhetoric of the President and representatives of executive and legislative bodies are filled with such propaganda.

47. Moreover, the authorities spread propaganda among children to build a Russian society that is more agreeable with the current regime. In the first days of the full scale invasion, the authorities issued recommendations to Russian schools to start conducting lessons for students in such a way as to convey the government’s position on the reasons for the invasion, as well as to condemn anti-war rallies. In March 2023, several regions held classes on fake news, where students were urged not to believe the reports of the Ukrainian authorities about the number of dead Russian soldiers.

48. In September 2022, Russian schools throughout Russia introduced ”Important Conversation” lessons, designed to instill in the school children the Russian government’s views about the war. The Russian authorities persecute children and their parents for refusing to attend such lessons. For example, Russian police interrogated and intimidated a fifth-grader from Moscow who skipped these lessons and expressed her anti-war opinion at school. The police also charged her mother with failing to fulfill parental duties and searched their house. In addition, the authorities apply various forms of pressure against teachers who refuse to hold such lessons, including disciplinary punishment and detentions. At least 19 teachers and 27 university professors were fired because of their anti-war position.

49. Non-state actors also spread pro-war propaganda in everyday life by demonstrating letters ”Z” and ”V”, organizing pro-war war events, and by other means. Such practice is widely endorsed by the state. The state practice of spreading and endorsing propaganda of war is inconsistent with human rights obligations under Articles 19 (freedom of expression) and 20 of the ICCPR (prohibition of propaganda of war, according to which states should refrain from any such propaganda or advocacy).

50. Since the start of the full scale invasion, the Russian government has also accelerated its use of rhetoric that incites hatred and violence against Ukrainians, including dehumanizing Ukrainian people and ”rejecting Ukraine’s existence as a state, a national group, and a culture”.

51. Russia is infamous for actively encouraging hate speech and violence against women and LGBTQ people. After the government passed the so-called gay propaganda law, which imposes fines for exposing children to homosexuality, online and offline violence against LGBTQ people was officially legitimised. Russian LGBT Network has documented a rise in homophobic vigilantes and anonymous groups like ”Pila” (”Saw”) who dox LGBTQ individuals online and offers rewards to anyone who ”hunts” them like animals. One person on Pila’s list, bisexual activist Elena Grigorieva, was killed in 2019.

52. Russian authorities are extremely reluctant to investigate crimes against LGBTQ people. They are keen to prosecute women and LGBTQ individuals for their online activities. Russian authorities filed criminal charges against feminist and LGBTQ activist Yulia Tsvetkova, requesting that she serve between two to six years in prison for managing a feminist social media page that encourages people to share body positive, artistic depictions of vulvas. After two years, the Russian court acquitted her, but the decision was overruled on appeal.

Internet shutdowns and website blockings

53. The government’s harsh policy of controlling content on the internet, putting pressure on tech platforms, blocking online resources, and implementing internet shutdowns entails massive violations of individuals’ rights to freedom of expression and freedom to disseminate information, among other rights.

54. The Sovereign Internet legislation has made it possible for the state to block at its discretion a number of foreign and domestic services and resources or slow down or throttle their work. In February 2021 Roskomnadzor (Russian Media regulator) slowed down the speed of Twitter, accusing the US social media company of failing to remove 3,000 posts relating to suicide, drugs, and pornography. That was the first massive application of the Sovereign Internet law.

55. During Russia’s 2021 parliamentary elections, authorities also used brute-force methods to coerce Apple and Google to take down the Smart Voting app created by associates of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, which was designed to help Russian voters identify candidates not in the ruling party that were most likely to win. Russian agents reportedly threatened Google’s local staff with jail unless the company removed the app within 24 hours. The Smart Voting website and Telegram were later subjected to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks that further limited user access.

56. Russia also has a history of internet shutdowns, including around elections. In 2019, the authorities shut down mobile internet in Moscow during protests over the Russian electoral commission’s refusal to register opposition candidates for local elections.

57. Russia also has a history of throttling mobile internet during protests. Accordingly, between 2018 and 2019, the local government in Ingushetia shut down the mobile internet during peaceful protests against the border agreement with the neighboring Chechnya. Ingush activist Murad Khazbiev challenged the shutdown in court, but the judges sided with the government and declared the shutdowns lawful. Khazbiev is now appealing the court decision at the European Court of Human Rights.

58. During the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, authorities are imposing social media shutdowns at home by blocking access to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, as well as to major VPNs and the Tor browser. Authorities are also blocking or otherwise silencing major independent media and human rights organisations. As of December 2022, Russian digital rights group Roskomsvoboda estimated that the Russian authorities blocked almost 640,000 websites inside Russia. According to Roskomsvoboda’s data, Russia has blocked an average of 4,900 websites per week in 2022. These actions have prevented Russians from accessing accurate information about the war and the associated human rights violations committed in Ukraine and Russia. It has also allowed Russian state war propaganda to flourish unchallenged, including in the Russia-occupied territories.

59. Rerouting internet traffic to Russian networks, blocking YouTube, Viber, and Instagram in the Ukrainian city of Kherson, and deliberately attacking TV and cell towers are all part of Russia’s strategy to seize complete informational control over Ukraine. According to Access Now’s 2022 #KeepItOn report on internet shutdowns around the world, since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian military cut internet access in Ukraine at least 22 times, engaging in cyberattacks and deliberately destroying telecommunications infrastructure.

Surveillance

60. Russia currently has one of the most extensive mass surveillance systems in the world.

61. The European Court of Human Rights has, on numerous occasions, declared Russia’s blanket interception of mobile telephone communications, which is common practice, unlawful. Yet the country’s Yarovaya law requires companies to store the content of voice calls, data, images, and text messages for six months, and their metadata for three years. Meanwhile, the DPI-based Russian System for Operative-Investigative Activities (SORM) serves as a technical framework for electronic surveillance not only in Russian, but also across Central Asia and Belarus, further harming privacy and free expression in the region.

62. Russia only increased its surveillance capabilities since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, rolling out a Face Pay system in the Moscow underground that uses facial recognition technology to allow passengers to pay for rides. According to Russian digital rights group Roskomsvoboda, Face Pay is ”a dual-use technology, which can be used on the one hand for the convenient use of transport, but on the other hand, for surveillance and capturing people’s personal data”. A notable example of the latter includes its use by authorities to justify detaining activist Mikhail Shulman for participating in political protests. NTech Lab and VisionLabs are the two leading Russian companies that supply facial recognition technologies to the Russian government.

63. Data collected through cameras is also at risk of being sold on the black market. Roskomsvoboda has documented cases of CCTV footage being leaked and sold online, with people paying to spy on specific individuals identified by the cameras. Given the limited access to such footage, law enforcement members are the most likely culprits behind the leaks.

64. Russia is also known for frequently hacking civil society and those critical of the regime. In 2021, Russia infiltrated the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) email system and sent messages to human rights groups, nonprofit organisations, and think tanks, with links to spyware that allowed the Russian government to surveil the recipients’ computer networks.

Recommendations

65. Repeal the laws unduly restricting the right to freedom of expression and access to information, including first and foremost Articles 207.3, 275.1, 280.3, 284.2 of the CC, Article 20.3.3 of the COA and the Federal Law No. 277-FZ dated 14 July 2022, and bring all other legislation into conformity with the international human rights standards on the freedom of expression, and refrain from adopting any further restrictions incompatible with the requirements of legality, legitimacy, and necessity and proportionality in Article 19 (3) of the ICCPR and the Human Rights Committee General comment No. 34;

66. Review national legislation and policies to fully guarantee the safety of journalists and media workers, human rights defenders, and activists so that these important actors can pursue their activities freely without undue interference, attacks, or intimidation;

67. Start investigations and hold accountable those responsible for harassment and attacks on journalists and civil society;

68. Repeal all the laws unduly restricting the rights to freedom of assembly and association, including the laws restricting the right to protest and the laws on "foreign agents" and "undesirable organisations" empty all relevant registries, and bring all legislation in compliance with human rights standards;

69. Ensure unrestricted access to alternative information and independent media for all people, including information on the war in Ukraine;

70. Stop spreading propaganda of war and inciting hatred and violence, including through statements and media appearances of state officials, and propaganda of war in the school system;

71. Remove all the blockings from media outlets and other independent sources of information, including the website of OVD-Info;

72. Refrain from shutting down the internet and blocking social media and make a state pledge to refrain from imposing any unlawful restrictions on internet access and telecommunication in the future;

73. Refrain from pressuring tech companies, internet service providers or other telecommunications companies to moderate content online in contravention of the rights to free expression and access to information and ensure their compliance with their responsibilities to respect and protect human rights in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights;

74. End mass surveillance programmes and ensure that any interference with the right to privacy is consistent with the principles of legality, legitimacy, necessity and proportionality;

75. Ensure unrestricted access to information about public events and stop the practice of prosecution of authors of social media posts about such events;

76. Refrain from arbitrary arrest, detention, and enforced disappearance of media workers, including as retaliation for their professional activities or expression; release arbitrarily detained media workers and provide remedies and reparation for human rights violations committed against them; and

77. Provide a report on the current detention conditions of all media workers held in detention centers and prison colonies in Russia (including, but not limited to, whether they are provided with access to legal counsel and family visits as required by law).

Photo: Detention of journalist Yevgeny Feldman at the “Freedom to Navalny!” rally. Moscow, January 23, 2021 / by Natalia Budantseva for OVD-Info