Доклад на русском языке: Как Конституционный суд влияет на региональные законы о митингах. Станет ли больше свободы собраний?

On 4 June 2020, the Russian Constitutional Court invalidated subfederal bans on rallies again: while in its ruling of 1 November 2019, the Court declared subfederal bans on rallies in front of buildings occupied by subfederal and municipal authorities null and void, this time it clearly condemned the general subfederal prohibitions on rallies in public places. From the empirical perspective, this «constitutional soap opera» shows the limited effectiveness of the Court’s usual trade-off between political rights and public security. As the figures show that the November ruling has not triggered substantial reforms of subfederal bans, the Court tried to clarify its position in June, eliminating abstract subfederal bans while permitting to hold rallies only in specially designated areas.

The Court’s initial limitation of assembly bans: a few steps forward without systemic changes

Since the 2012 amendments to the Federal Law on Public Events, constituents of the Russian Federation introduced their own extensive territorial restrictions on the freedom of assembly. According to a Russian NGO, OVD-Info, it resulted in large areas of main Russian cities becoming unsuitable for public rallies.

In this context, in its ruling of 1 November 2019, the Constitutional Court of Russia was impelled by ECHR ruling in Kablis v. Russia to invalidate the law of the Komi Republic that prohibits holding public events within fifty meters from the buildings of subfederal and municipal authorities, as well as in the Stefanovskaya Square of Syktyvkar, the city’s main historical venue. As for the substance of its ruling, the Court excluded blanket subfederal bans but it authorised the constituents to enact vast, if balanced, territorial restrictions. The Court instructed the other subfederal lawmakers to comply with these new confusing standards.

According to OVD-Info data, since 1 November 2019, 42 subfederal states have reformed their legislation allegedly to comply with the Court’s November ruling. In the reformist states, the Court’s ruling failed to compel the subfederal authorities to carry out a comprehensive review of enacted prohibitions on the freedom of assembly. If the figures show progress in dismantling prohibitions on events in front of public buildings and some other places, the bulk of unconditional restrictions were not affected or were even tightened, defeating the lifting of bans for public buildings.

Bans on rallies in front of public buildings were (partly) removed

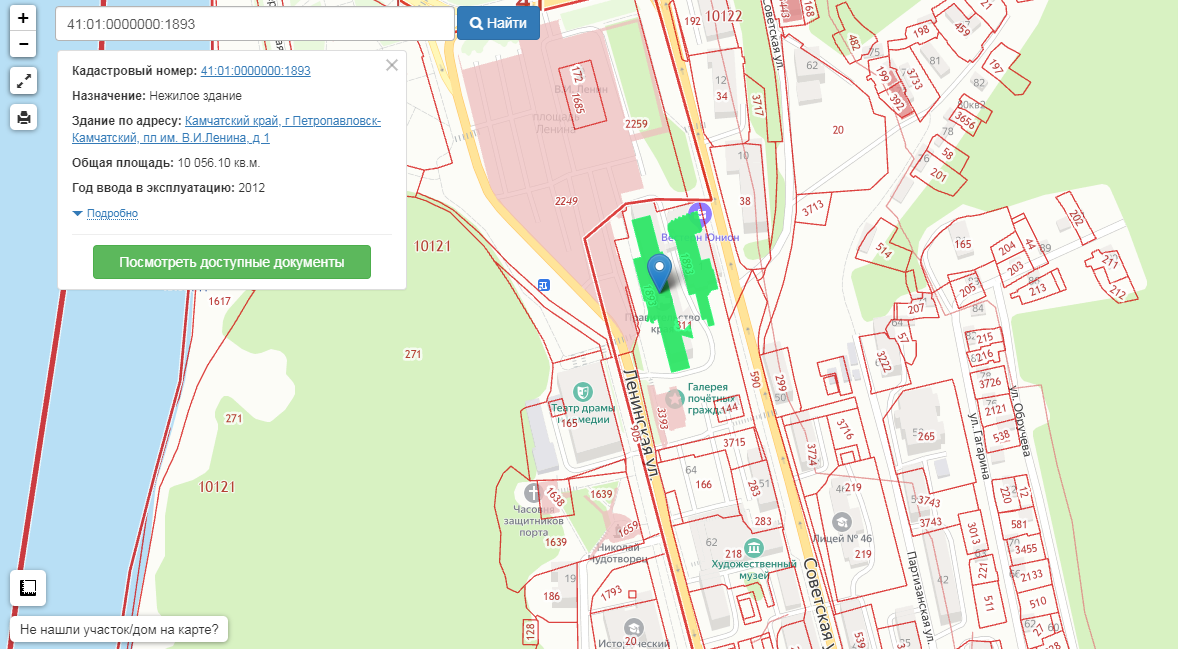

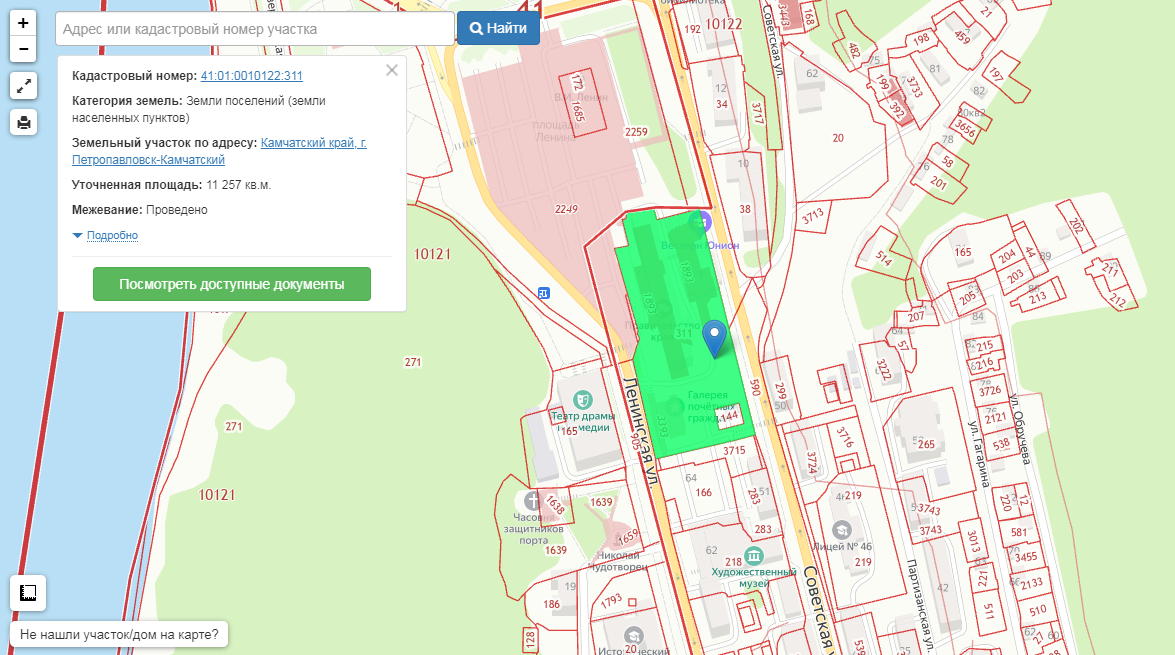

As this kind of bans was clearly censured in the Court’s obiter dicta, it was just repealed in 37 (out of 47 concerned) constituents. In Dagestan, a similar ban was annulled (but still not excluded from the statute) by the subfederal constitutional court. There are 10 constituents which still have not complied with the ruling (Tver, Bryansk, Belgorod, Yaroslavl, Sverdlovsk and Leningrad regions, Stavropol and Kamchatka territories, Karachay-Cherkessia and Dagestan).

However, even after these clear instructions from the Court on areas adjacent to public buildings, consistent compliance was not achieved.

First of all, not all public buildings were covered by the reforms. Thus, in 7 constituents, prohibitions of rallies remained in place for fire stations and military units, which have a status of governmental bodies, not to mention that many regions maintained this ban for educational, social and cultural centres, which fall into the category of public establishments.

Furthermore, 22 constituents upheld or introduced bans on any public events, even meetings, inside public buildings. It certainly could have an adverse effect on the work of representative bodies, as since 2017, official meetings of MPs with citizens in official buildings have been essentially allowed, without prior notification of the authorities. Not to mention that holding such official events as public hearings, citizen conferences and residences’ councils is provided for by federal law. Therefore, the new regulation could hinder opposition activity in the deliberative bodies.

Finally, the formal repeal of a full ban could be just concealed in other restrictions. It is the case in Tatarstan and Tuva, which instead of a full distance ban for public buildings introduced new restrictions for protected public locations in the counter-terrorism legislation. The list of banned areas prepared by municipal authorities covers 250 areas only in Kazan, including Kazan City Hall, the buildings of Tatarstan’s executive and legislative bodies, as wells as of some other governmental bodies.

Other general bans on public space were not crucially concerned

Only a few (12) regions dared to dismantle their bans other than those for public buildings. For example, 8 constituents lifted bans for areas adjacent to social and educational institutions and transport infrastructure (Kabardino-Balkaria, Kemerovo, Kurgan, Oryol, Amur, Ryazan, Penza and Pskov regions). Abstract bans were also lifted in the Moscow region (markets and shopping centers), Bashkortostan (garden plots) and Kuzbass (children’s activities).

However, 75 constituents of the Russian Federation have this kind of bans which could virtually neutralize the removal of the ban for public buildings. For example, in the Astrakhan region, while space in front of public buildings has become free for rallies, it would be still impossible to hold a gathering near the Governor’s office as it is located within an area adjacent to schools, which is subject to existing bans.

Bans for specific locations are still valid in 8 regions. The overall number has not changed, as this ban was repealed in the Komi Republic (in exchange for new abstract bans) and introduced in the Oryol region (instead of abstract prohibitions).

Moreover, compliance with the Court’s ruling gave rise to new restrictions and consolidation of existing ones. Some regions (Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Tatarstan, Tuva and Vologda) have chosen to replace old blanket bans with new «contingent» ones where holding public events is allowed, provided there is no real threat to public order. Consequently, since the legislator abstained from deciding whether an area is prohibited for public events, it expands the discretionary power of administrative bodies and creates uncertainty for the organisers of public events.

Similarly, some constituents added new restrictions while seemingly complying with the Court’s ruling. Thus, in Tatarstan, the new law introduced contingent bans on social, transport, cultural and sports infrastructure, recreational facilities for children and disabled persons. Similarly, the Tomsk region expanded the ban on public events from children’s playgrounds to venues for mass events, open water bodies, bus stops, pedestrian crossings, areas near railways and car parks, airports and medical institutions.

In the end, 4 regions are lifting all territorial bans on the freedom of assembly (Kurgan and Arkhangelsk regions, Yamalo-Nenetsk Autonomous District and, thanks to subfederal constitutional justice, Ingushetia).

The Court becomes more radical — also in opposing free assemblies?

The limited impact of the Court’s November ruling on the removal of subfederal bans was not just a result of subfederal creativity, but the Court’s hard compromise of liberal and security-driven approaches. The Court left plenty of room for subfederal restrictions when it allowed for an extensive list of public interests as grounds for bans (threats to «the functioning of critical facilities, transport and social infrastructure, communication facilities, human or automobile traffic, as well as citizens’ access to housing, transport and social infrastructure»).

Nor did the Court clarify explicitly the delegated mandate of subfederal legislature, other than that it should be justified by specifics of a given constituent. In particular, the Court censured the subfederal ban on public buildings as extending federal restrictions of the freedom of assembly, meaning that the field of subfederal bans should be outside of the federal bans. It should be said that during the discussion of recent subfederal reforms following the Court’s November ruling, the legislatures were never questioned whether or not all statutory bans, and not just those on public buildings or certain other areas, were justified by evidenced-based regional needs.

The scope of subfederal bans based on subfederal specifics was clarified by the Court in its ruling of 4 June 2020. The Court stressed that subfederal restrictions should not be abstract in nature (i.e. generalized). However, they could be introduced by subfederal legislative bodies based on the specifics of a given area or facility. As for federal jurisdiction, the Court pointed out that subfederal restrictions could not cover the facilities which were not mentioned in the federal statute. It has therefore invalidated Samara region’s ban on rallies near the military facilities, clinics, schools and churches as inconsistent with respective federal laws. Looks like the Court’s bell tolls for the bulk of existing subfederal bans on rallies. We prepared a detailed study on which regions should amend their laws on rallies after the June ruling, and asked the Presidential Human Rights Council to monitor the situation.

However, the Court would not have been true to itself if not it did not make two steps back after a progressive step forward. In order to compensate for the drastic reduction in the scope of subfederal bans, the Court proposed the Russian Parliament to expand the existing list of federal bans on public events, if so required for a given constituent.

Similarly, in obiter dictum, the Court made an adverse reinterpretation of the role of specially designated areas for public events (so-called «hyde parks») regulated by subfederal authorities. Indeed, the amendments to the Federal Law on Public Events enacted in 2012 specified that once the subfederal authorities determined such specially designated areas, public events should «normally» take place there. In its 2013 ruling, the Court neutralised this restrictive meaning declaring that such areas should be an additional guarantee for the organisers of public events. This time, the Court said that public events should be held principally in authorized areas, unless the event organisers prove that the event could not be held there for objective reasons.

The Court surely tried to mitigate case law reversal, where permitted-unless-prohibited was replaced with permitted-only-where-expressly-allowed. Besides referring to verified connection of the planned event with specific areas outside of specially designated areas, the organisers of an event could also argue that the areas chosen by regional authorities as allowed for public events are not fit for holding open public events.

However, events in specially designated areas are overregulated by subfederal laws to the point where the conditions that organisers should meet are not easier than for ordinary areas, commencing with the notification procedure. As for the judicial review, the courts tend to agree with administrative authorities proposing to hold event in an authorised area, without questioning the justification of such decisions.

Thus, the Court preferred its usual halfway measures, giving a new life to restrictions on the freedom of assembly. Time will show which aspect of the Court’s new framework for rallies will be applied in practice. Anyway, it is law enforcement that will have the last word.