Текст на русском: Как подавляют протесты в Хабаровске

Introduction

Khabarovsk Krai is a region in the Russian Far East with a population of almost 1,5 million people. In July 2020, protests started in Khabarovsk and other cities of the region in response to the arrest of the former governor of Khabarovsk Krai, Sergei Furgal, who has faced grave criminal charges. Furgal was very popular in the region and many residents considered his case to be politically motivated. The protests go on to this day.

Sergei Furgal, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) member, was elected as the governor of Khabarovsk Krai in September 2018. In the first round of elections, he was ahead of the incumbent governor Vyacheslav Shport (from United Russia) by 0,19 percentage points, in the second — by more than 40 percentage points, even though he virtually did not campaign. Back then this result was interpreted as the population’s tiredness of the incumbent governor and of United Russia in general (during those elections, a similar situation arose in some other regions.)

The wave of protests that started in Khabarovsk Krai was picked up by other regions as well. Rallies in solidarity with Khabarovsk residents took place across the country. At the same time, the Khabarovsk protesters showed their support for the people of Belarus and for Alexei Navalny following his poisoning.

As it often happens in Russia, in response to protests, the authorities started to pressure the protesters and the journalists covering the events. The pressure became especially pronounced when then-interim governor Mikhail Degtyarev, who emphatically distanced himself from the protests, arrived in the region. The authorities used various methods: opening administrative and criminal cases, exercising extrajudicial persecution.

At the end of July 2020, the coordinator of the Open Russia movement Sergei Naumov arrived in Khabarovsk from Komsomolsk-on-Amur to cover the protests in the media. The same day, he was attacked by two men. After the incident, Naumov came to the police to file a report. When he was leaving the police department, he was detained and accused of participating in an unauthorised event. After compiling the detention report, the police kept Naumov at the department until the court hearing. The court arrested him for ten days.

Mostly, peaceful protesters like Naumov are charged with Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation (violation of the procedure for holding a public event). Apart from administrative charges, the protesters also face criminal ones. There are three cases under Article 318 of the Criminal Code of Russia (on the use of violence against police officers) and one under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code (on repeated violations at public assemblies). Under both articles, the maximum sentence is up to five years in prison.

Sergei Naumov was detained multiple times, like another regular protester Rostislav Smolensky (also known as Rostislav Buryak). Smolensky is the owner of the «Furgalomobile» or «Furgal Vehicle», which is one of the main symbols of the Khabarovsk protests. Initially, this minibus was used as a food truck. Eventually, it got covered with posters in support of Furgal and was leading the column during the marches. Rostislav started receiving threats; he was detained and arrested several times. Next, «Furgalomobile 2.0» appeared as Andrey Maklygin decided to express his protest and stuck posters to his car. He was detained and arrested numerous times, too. At the beginning of December, Maklygin said that an operative from the Centre for Extremism Counteraction called his teenage son and insisted that the boy should convince his father to stop participating in protests. Afterwards, the law enforcement authorities were considering filing criminal charges against Maklygin: it was alleged that he insulted a traffic police officer.

«I am proud of being a journalist, of having worked in this field for 22 years and living in a state under the rule of law in which the rights of all categories of citizens are respected, including mine, ” journalist Ekaterina Biyak wrote in her offence report. In the middle of November, she covered the events at Lenin Square where protesters gathered. Biyak was detained and the police drew up an administrative offence report under Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (participation in an unauthorized event which resulted in the obstructed functioning of city infrastructure facilities and movement of motorized vehicles). She was kept at the police department all night. Later she was fined, detained again, the police drew up another report under Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1. After spending another night at the department, Biyak was arrested for two days. Ekaterina says that the pressure against journalists is «an attempt to extinguish civic activism.»

In this report, we will discuss the scale and methods of pressure exerted against Khabarovsk Krai protesters, and the variety of distinctive methods employed by the local authorities to suppress the protests.

The Annex to the report provides the statistical data collected by OVD-Info and brief descriptions of cases against the activists supporting Khabarovsk Krai in other regions.

Characteristics of Protests

Spontaneous Protest

The first protest event took place in Khabarovsk at Lenin Square on Saturday, July 11, two days after the detention of Khabarovsk Krai governor Sergei Furgal. Protests were happening in other cities of the region as well, for instance, in Komsomolsk-on-Amur. According to various sources, 10 to 60 thousand people participated in the rally in Khabarovsk.

Under Russian law, the authorities must be notified about any form of a rally except picketing no later than ten days in advance. For group picketing, the notification must be submitted three days in advance. Such rules do not allow to react quickly to current events. For the cases when, due to urgency, the organizers are unable to comply with all formal requirements to the notification of authorities, or a gathering does not have any organizers, the international standard on the right to freedom of assembly introduced a notion of spontaneous assemblies. The first protests in support of Sergei Furgal in Khabarovsk Krai qualified as such.

It should be noted that the Khabarovsk Krai police meticulously followed the requirements of international law concerning the participants of spontaneous assemblies, and did not detain anyone. The first arrests were recorded on the night of July 12, but until October 10 they were not massive. Participants of regular protests were subjected to administrative liability mainly after the event: they were summoned to police stations to draw up reports or detained after the end of rallies, often not on the same day. (For more details, see the section Detention and Administrative Prosecution.)

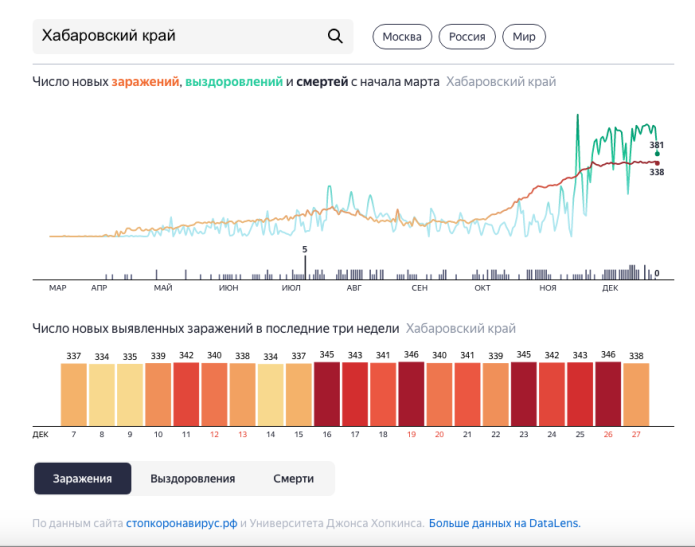

Pandemic Restrictions (2020)

Mass protests in Khabarovsk started between two waves of COVID-19 pandemic in Russia, due to which the authorities introduced a number of restrictions. Among other things, conducting public events was subject to these limitations. In Khabarovsk Krai, a high alert regime due to coronavirus infection was introduced by the governor’s order on February 13, 2020. However, restrictions for citizens were not imposed then.

On March 17, by the order of the minister of culture of Khabarovsk Krai, cultural events (holding more than 600 participants for urban districts and more than 100 participants for rural areas) were prohibited. At the same time, the document did not say anything about the prohibition of public events, such as rallies, marches, demonstrations and picketing, including single-person pickets.

However, as soon as March 26, the regional government prohibited holding «leisure, entertainment, cultural, athletic, sports, exhibition, educational, advertising, public and other events with the presence of citizens on site.»

On June 10, the region began gradually lifting the restrictive measures. For example, summer cafes, public baths, museums, etc., resumed their work. The public events were originally supposed to resume on June 20, but it was postponed several times until the respective resolution of the regional government was annulled in early September. New rules came into force in the region on September 4, and formal restrictions on public events were lifted. At the same time, the mask regime and social distance of 1,5 meters in crowded places were still required. On October 9, additional rules came into force, specifically prescribing to keep social distance at public events.

On October 16, 2020, public events with more than 50 participants were banned in Khabarovsk Krai. At the beginning of November, the maximum number of participants in public events in the region was reduced to 25 people.

Thus, the official approval of public events (upon the application from organisers) became possible in Khabarovsk Krai only from September 4, 2020. At the same time, since mid-October, 2020, it became impossible again to have a large public event officially approved by the authorities in the region. It is worth noting that in terms of restrictions on freedom of assembly due to the pandemic, Khabarovsk Krai was not unique: similar measures were taken in many regions of the country.

Restrictions on freedom of assembly due to the pandemic on a global scale have raised serious concerns among experts. For instance, Clément Voule, the current UN Special Rapporteur on Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association, pointed out the following problems in April 2020: «Restrictions based on public health concerns are justified where they are necessary and proportionate in light of the circumstances. Regrettably, civil society organizations have rarely been consulted in the process of designing or reviewing appropriate measures of response, and in several cases, the processes through which such laws and regulations have been passed have been questionable. In addition, those laws and regulations have often been broad and vague, and little has been done to ensure the timely and widespread dissemination of clear information concerning these new laws, nor to ensure that the penalties imposed are proportionate, or that their implications have been fully considered. In many cases, it appears these measures are being enforced in a discriminatory manner, with opposition figures and groups, together with vulnerable communities, constituting prime targets.»

The situation with restrictions on assemblies in Khabarovsk Krai clearly illustrates many of the problems listed above: restrictions were introduced by decrees of the executive authorities, not laws; specific measures were not discussed with human rights experts or civil society representatives; the duration of the restrictive measures was constantly shifting; the restrictions themselves were discriminatory: assemblies and public expression of opinions were prohibited, while other forms of mass gathering, such as entertainment, were permitted. A good illustration of the fact that restrictive measures were not clear and were not brought to the attention of the population in a timely manner is the case against the Russian Communist Party members for holding a rally against political repressions on July 17.

«De jure, there was no ban on this event, we have notified everyone. But we are told that there was a ban. Only the governor or an acting interim could extend this resolution [banning public events], and Furgal was detained on July 9, there was no acting or interim governor in the region at that time, ” explained one of the organizers of the Communist Party rally. This situation is partly due to the fact that from June 20 to September 4, the date of lifting the bans on public events was repeatedly postponed. As a result, even members of large political organizations, such as the Russian Communist Party, were unable to figure out which rules were in force.

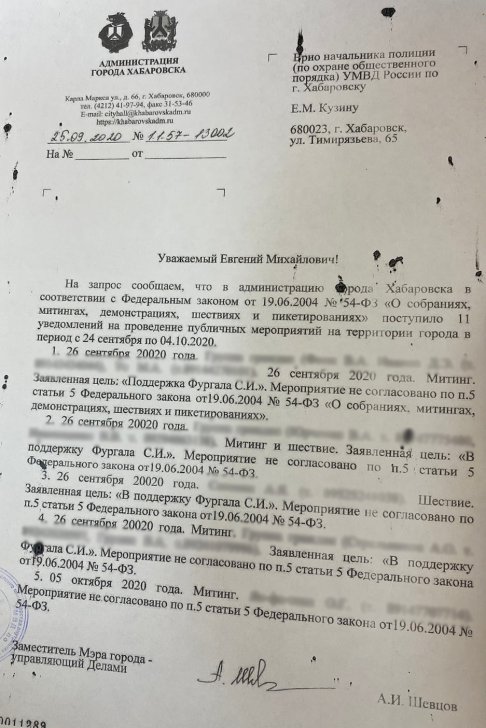

Attempts to obtain approval of events

Immediately after lockdown restrictions were lifted in early September, the activists tried to notify the Khabarovsk city authorities of their intention to hold a rally and a march in the city. A rally with tens of thousands of participants was approved by the authorities for September 12. «We submitted the notice of our rally to the city administration as early as on Monday [August 31, 2020 — OVD-Info]. We wanted to have a rally and a march for Furgal approved for September 5. But we did not meet the legal deadline, so we were turned down. Then we submitted a notification to hold an event on September 12. The Khabarovsk mayor’s office approved it for us, ” commented Andrei Dudenok, one of the protest organizers.

It is worth noting that the city authorities refused to approve the event at Lenin Square in front of the regional government headquarters, where protest rallies used to be held. Khabarovsk City Hall cited the fact that Lenin Square is under the jurisdiction of regional authorities and suggested holding the event at Komsomolskaya Square, which is the city’s «hyde park» — that is, a place where public events can be held without authorization.

Under the regional law on public events, the regional authorities have to be notified only about protests held simultaneously in several municipal districts or city districts (for example, when a rally takes place at the border between two districts or a march proceeds from one district to another). This rule does not apply to Lenin Square, since the entire Khabarovsk city is one city district. Hence, it is not clear why the city authorities suggested that the public event should be authorised by the regional administration.

However, the attempt to obtain approval for the rally at Lenin Square from the regional authorities was also fruitless, the organizers were turned down. The excuse was that another previously agreed event was to be held at the square during the time in question.

Subsequent attempts to obtain approval for a public event from the city authorities in Khabarovsk also frequently proved to be unsuccessful. From September 24 to October 4, 2020, Khabarovsk City Hall received 11 notifications regarding public events, and in all cases, the organizers received refusals citing Article 5, paragraph 5 of the Federal Law on Assemblies: «The organiser of the public event shall have no right to hold it if the notice of holding the public event was not filed in due time or no agreement was reached with the executive authority of the subject of the Russian Federation or local self-government body as to the alteration at their motivated proposal of the place and/or time of holding the public event.»

This could mean that the organizers and the authorities were unable to agree on the time and place of the action, or that it was not possible to comply with the deadline for submitting the notification.

On October 10, the first protest rally in support of Furgal, approved by the city authorities, must have taken place in Komsomolsk-on-Amur. One day before the rally, the authorities revoked the approval, citing the newly enacted rules for keeping social distance during public events. But since public events as such were not banned in the Khabarovsk region — only additional requirements have been introduced — hypothetically, nothing prevented the city authorities from asking the event organizers to ensure the distance between the protesters, rather than the event.

The excessive complexity and, in some cases, impossibility to get a public event approved or to hold an already approved one, called into existence the mass «pigeon feedings» at central squares both in Khabarovsk itself and in other Russian cities. A popular video blogger Alexei Romanov was the first to invite the Khabarovsk residents to come out on the streets to «feed pigeons». This form of protest saved the need for approving and organizing the public event, at the same time allowing people to publicly express their opinions and their solidarity with the protesters in Khabarovsk.

Peaceful Nature of Assemblies and Claims of Authorities

In addition to lockdown restrictions and the impossibility of getting approvals, the authorities see a number of issues with the protest rallies in Khabarovsk.

Firstly, they are worried about the noise and inconvenience to other residents of the city.

- On July 14, the press service of the city administration said there were numerous complaints from citizens about noise from the gatherings: «We received more than two dozen calls with complaints about the noise. Elderly people develop high blood pressure, and students can’t sleep before their exams. We are working with law enforcement bodies on this issue.»

- The court rulings that held the protesters administratively liable emphasize the fact that they «chanted» or «shouted» slogans using a loudspeaker.

Secondly, the protests allegedly obstructed the passage of pedestrians and vehicles.

- During a meeting of the regional government before one of Saturday protests, on September 25, Mikhail Degtyarev, the region’s then-interim governor, demanded «to bring order to Khabarovsk and other areas.»

- «For two months we have been witnessing hindrances to road traffic, road closures and hearing car horns honking <…>. Where there are honking and closures, there will be other traffic violations, ” Degtyarev said.

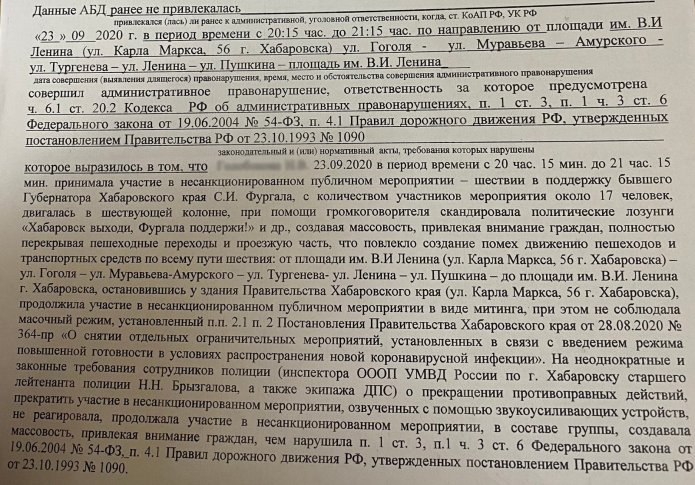

Accusations of hindering transport and pedestrian infrastructure form the basis of the vast majority of police reports, and subsequent court decisions to impose administrative penalties.

According to an administrative offence report, one of the protesters has been charged with «participating in an unauthorised public event in the form of a march of about 17 people in support of the former Khabarovsk Krai governor Sergei Furgal, moving with a marching column, chanting political slogans ‘Khabarovsk come out, support Furgal, ’ etc., using a loudspeaker, contributing to mass participation, attracting attention, completely obstructing pedestrian crossings and the roadway, from 8.15 pm to 9.15 pm <…>» on September 23.»

In the court order of ten days’ detention for a participant of the October 24 rally, the offence was described as follows: «From 12.30 pm to 01.30 pm [he] was participating in an unauthorised public event in the form of a march in support of former Khabarovsk Krai governor S.I.Furgal, of about 373 participants in total, moving with a marching column, contributing to mass participation, attracting attention, fully obstructing pedestrian crossings and the roadway.»

Similar factual descriptions of the charged offences were given in another court ruling that fined a participant of the October 10 rally 20,000 roubles: «[He] was participating in an unauthorised public event, the march in support of former Khabarovsk Krai governor S.I. Furgal, with about 100 participants, moving in the head of the marching column while holding in his hands a placard with the picture of S.I. Furgal and explanatory captions, thus contributing to mass participation in the event, fully obstructing pedestrian crossings and the roadway, which created hindrances to pedestrians and vehicles along the whole way of the march: **** — ****, not wearing a face mask as required.»

Thirdly, the authorities were very unhappy with any attempts to set up tents or other temporary structures at the site of the protests.

The protest of October 10 was dispersed by police after they received information about tents being set up at Lenin Square, in front of the regional government headquarters. The press service of the Khabarovsk city administration stated that «the law enforcement officers were forced to intervene and to convince the protesters to remove the tents. As the participants refused to do it voluntarily, the illegal structures were dismantled by law enforcement officers.»

It is not only Khabarovsk officials who are unhappy with the idea of tents. In the summer of 2019, during the protests against the non-admission of independent candidates to Moscow City Parliament elections, attempts to set up tents were also followed by detentions.

In the official discourse, tents are inextricably linked with the idea of a coup like the Ukrainian «Maidan» revolution. «Remember tent sites during the Maidan, and look how that turned out. By the way, the Ukrainian government allowed to set up tent sites at first, and then introduced restrictions: these tents were to be set up outside of the city centre. But then they were set up illegally in the city centre again, ” said Igor Zubov, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, at the reading of a bill on the mandatory authorization of single-person protests with the use of temporary structures in February 2016.

Meanwhile, paragraph 18 of the OSCE Guidelines on Freedom of Peaceful Assembly states the following regarding this kind of situation at public protests: «The question of at what point an assembly can no longer be regarded as a temporary presence (thus exceeding the degree of tolerance presumptively to be afforded by the authorities towards all peaceful assemblies) must be assessed according to the individual circumstances of each case. Nonetheless, the touchstone established by the European Court of Human Rights is that demonstrators ought to be given sufficient opportunity to manifest their views. Where an assembly causes little or no inconvenience to others, then the authorities should adopt a commensurately less stringent test of temporariness <…>.»

The reference section of the same document gives an example of a situation where the court sided with protesters who set up tents: «In the United Kingdom case of Tabernacle v. Secretary of State for Defence [2009], a bylaw of 2007 that prohibited setting up tents, caravans, treehouses, etc. in ‘controlled areas’ was recognized as violating the complainant’s rights to freedom of expression and assembly. The court noted that the particular manner and form of this protest (a camp) had already acquired symbolic significance inseparable from its message.»

The listed reasons for discontent on the part of authorities have become grounds for dispersing protests, as well as for detentions, administrative and criminal prosecution of participants. Meanwhile, it is the peaceful nature of assemblies that is the key factor in determining whether they qualify for legal protection or not. Article 31 of the Russian Constitution affirms «the right to assemble peacefully, without weapons,» and nearly all international human rights documents underline that the freedom of peaceful assembly is guaranteed. On their own, setting up tents or other temporal constructions, lack of authorisation, obstructions to vehicles or noise are not signs of a violent character of such events. The authorities themselves do not challenge the peaceful status of Khabarovsk protests. «As before, the event is held peacefully, with calls to release the former governor or to hold an open court hearing,» stated the Khabarovsk city hall in early August.

In the view of the European Court of Human Rights, an assembly remains peaceful if its organisers and participants do not «have violent intentions, incite violence or otherwise reject the foundations of a democratic society». Furthermore, isolated acts of violence do not automatically make the assembly non-peaceful.

The UN Human Rights Committee noted the following in its definition of the right of peaceful assembly that is enshrined in Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: «The right of peaceful assembly may, by definition, not be exercised using violence. ‘Violence’ in the context of Article 21 typically entails the use by participants of physical force against others that is likely to result in injury or death, or serious damage to property. Mere pushing and shoving or disruption of vehicular or pedestrian movement or daily activities do not amount to ‘violence’.»

Several criminal cases were initiated under Article 318 of the Russian Criminal Code (infliction of physical harm to a law enforcement officer) toward the participants of protests in Khabarovsk. The charges and actual circumstances indicate that the cases are associated with response to the actions taken by police, and these were isolated actions not caused by the nature of the assemblies. (For more details, see the Criminal Cases section).

The above-mentioned UN Human Rights Committee’s explanation states that «the conduct of specific participants in an assembly may be deemed violent if authorities can present credible evidence that, before or during the event, those participants are inciting others to use violence, and such actions are likely to cause violence; that the participants have violent intentions and plan to act on them; or that violence on their part is imminent. Isolated instances of such conduct will not suffice to taint an entire assembly as non-peaceful <…>.»

Thus, in the case of a peaceful assembly, its participants enjoy the right to legal protection regardless of whether or not an assembly was approved by authorities, of the epidemiological situation or of temporary inconveniences for others. It means that any restrictions and measures taken against the participants of peaceful assemblies in a democratic society must be provided by the legislation, commensurate with the circumstances and caused by clear necessity.

See below a review of measures applied to the participants of peaceful assemblies.

Detentions Associated with Protests

Overview of detentions

From July 11, 2020, when the protests in support of Sergei Furgal started, till December 1, 2020, OVD-Info has registered 64 detentions at 15 events in Khabarovsk Krai, whereas 12 detentions took place in summer 2020 and 52 — in autumn. Almost twice more, 121 cases of detention, took place within the periods between the protests (for more details, see below.)

Typical issues with detentions

The analysis of detentions of participants at protests in Khabarovsk Krai allows distinguishing several types of violations of the detainees’ rights that are also typical for many other regions of Russia.

The participants have not been warned that they were violating prior to their detention.

The law enforcement officers did not introduce themselves during detentions and did not specify the detention cause.

- On November 28, 2020, Alexander Naumenko, a participant of a daily march in Khabarovsk was detained after the event and, as noted by reporters, at an intersection far from Lenin Square where the rally took place. The policemen neither introduced themselves nor explained the cause of detention or their presence at the intersection.

- A participant of protests Konstantin Panchenko was detained next to his residence building where a group of policemen had been waiting for him. The officers refused to explain the cause of the detention and just said that «everything will be explained at the police department». During the detentions, the law-enforcement officers used excessive force.

- On July 29, a woman and her son were detained in Komsomolsk-on-Amur after a public rally in front of the city administration headquarters. During the detention, the young man was knocked to the ground, beaten and kicked. In a few cases, the law enforcement officers dispersed the rallies: they did not detain isolated participants but acted with the purpose to stop the rally.

- On October 10, the riot squad police were engaged to disperse a rally in Khabarovsk. The witnesses reported that some of the law enforcement officers appeared from the building of the regional government and detained the protesters without any warning. A participant of the October 10 rally Alexey Vorsin told about his detention: «The riot squad police started grabbing and hitting people, I was detained and put into the police bus.» According to OVD-Info data, at least 30 people were detained.

- The press service of the city administration explained the police actions: «The protesters have pitched their tents in a demonstrative manner right on the lawns of the city’s main attraction. Three such structures were set up.» Next to the tents, the participants placed large-size loudspeakers to transmit slogans, which, according to the spokesperson, caused «serious inconvenience to the pedestrians who were walking across the square», and this is why the law enforcement officers «were forced to intervene and convince the protesters to remove their tents.» «As the participants refused to do it voluntarily, the illegal structures were removed by the police, ” the press service said.

- On November 2, policemen and traffic police officers dispersed the column of protesters marching along the street and chanting «Khabarovsk, come out!» A blogger Angel ID (Andrey Solomakhin) broadcasted the dispersal on his YouTube channel. According to activists, when the column was marching along Lenin street, five police vehicles approached them. «They jumped out, started grabbing and detaining people who were just standing at the bus stop, chasing them. The policemen made no lawful demands, just attacked the people, » said the YouTube broadcast reporter. At least two protesters were detained.

Protest participants reported that the Centre for Combating Extremism and Federal Security Service employees were involved in detentions.

- On July 26, acting Khabarovsk Krai governor Mikhail Degtyarev had a public meeting near the regional government headquarters. After the meeting, one of the most active protesters stated that one of the meeting attendees was a Federal Security Service officer. The protester was attacked by strangers in plain clothes who also had been at the meeting. After that, the police detained the protester.

- On October 10, the witnesses to the rally dispersal noticed that a Centre for Combating Extremism employee in plain clothes instructed OMON policemen on whom to detain.

- On November 26, Centre for Combating Extremism employees tried to enter a protester’s apartment. They were trying to break down the door for more than an hour, and cut off the apartment’s electricity.

Another type of violation of the detainees’ rights is that the law enforcement officers detain not only protesters but also random passers-by and journalists who cover the protests.

- On November 7, five people were detained during the march in support of Furgal, including one person who did not participate in the rally, but was only filming it.

- On November 12, two persons were detained at Lenin square: journalist Ekaterina Biyak and YouTube blogger Boris Zhirnov. Biyak was covering the protest. After the majority of the protesters departed, the policemen came to the journalist and told her to go with them to a police department. Zhirnov who was standing nearby was also detained. Later, Biyak wrote in her police report: «I am proud of being a journalist, of having worked in this field for 22 years and living in a state under the rule of law, where the rights of all categories of citizens are respected, including mine.»

- On November 14, two protesters and one journalist were detained.

During detentions, law enforcement officers unreasonably apply force to protesters, use physical and emotional violence.

- Journalists reported that during the protest dispersal on October 10, the law enforcement officers took two minors into the regional administration headquarters. The policemen handled the teenagers roughly and made them kneel in a corner with their heads down. Another protester said that after a riot policeman hit her she got a hematoma on her head. Doctors confirmed that one of her teeth and a part of her jaw split up. A metal fragment was found inside her jaw tissue. Probably, that was a piece of the object with which she was hit. Two other detained activists were taken to hospital: one had excessive bleeding from the nose, the other — soft tissue bruises on of the torso, limbs and head.

- On October 11, three Federal Security Service employees talked in a police department to a citizen detained after the protest. The law enforcement officers asked the protester if he «had a normal life». They threatened to «kick his parents out of their jobs» and get him expelled from the college. They also threatened to pull out the ring from his nose. The officers wanted to know «who leads the protesters».

Among other things, law enforcement officers deprive the detained of the right to receive medical treatment.

- On August 27, Albina Chuykova, a protester, was detained near her house. She felt unwell at the police department because of her chronic condition. The policemen refused to call an ambulance. Chuykova was hospitalized only after the interference of the prosecutor. Police drew up a report charging her with participation in an unauthorized protest, which resulted in the obstructed movement of motorized vehicles and pedestrians (Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offenses). Due to these charges the police retrieved Chuykova from the hospital and brought her back to the detention centre.

- On December 5, police officers detained a protester Tatiana Lukyanova in a bus. At the police department, she felt unwell. An ambulance came and found out she had high blood pressure. Also, Lukyanova had a disability due to an oncological condition. But her relatives did not manage to bring her papers to the department, and policemen refused to accept as proof the documents that the protester had on her. They drew up a report and placed her at the detention centre until trial.

Those who are kept at police departments overnight are not provided with proper conditions.

- Protest participant Alexander Prikhodko was kept overnight at the police station without water and food.

Regional Specific Issues with Detentions

There is a specific feature of prosecution of the protesters in Khabarovsk Krai: the majority of detentions takes place not at the rallies themselves, but between them. As of December 2, 2020, OVD-Info knows of 121 cases of detentions connected to the rallies in support of Furgal but not during them (see Annex). Some activists have been detained more than once. Protesters were detained near their houses at least 29 times, during a taxi ride or in a personal car — 11 times, and 9 cases of detention took place when the protesters were leaving the detention centres after having served their administrative arrest.

What is specific about the Khabarovsk police attitude to the protesters is that they tend to deprive detainees of any information. Also, they try to grab activists outside the rally locations, so that the detention would not attract the attention of journalists and bloggers covering the protests.

- On August 27, civil activists Albina Chuykova and Evgeny Mazikin were sitting in a parked car near Chuykova’s house when policemen approached them and said that their seat belts were not fastened. Mazikin was fined on the spot and released. Chuykova was brought to the police department, where police officers drew up a report charging her with participation in an unauthorized protest, which resulted in the obstructed movement of motorized vehicles and pedestrians (Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation).

- Nikolay Vasilevsky was detained when he was running errands with his mother. Near their house, Vasilevsky and his mother were approached by policemen, who introduced themselves as «criminal police officers», and took the man to a police department.

- On November 21, activist Vladislav Zakamov was detained at a bus station. On the way to the police department, police officers took his mobile phone away from him. No information about the detained activist was available until OVD-Info lawyer Andrey Demidov arrived at the police department.

- Protester Evdokiya Bogolyubova said that on December 5 she was detained at a tram station by two policemen and five Centre for Combating Extremism officers.

- On August 12, police officers detained a protester on a bus. Ludmila Koroteeva, 65, got into the vehicle when police officers crashed in and took the woman to a police department. She was illegally fingerprinted because she did not have her ID on her.

- Roman Denisov was detained at his workplace and taken to a police department, where two reports were drawn up. He was taken to court, but the trial fell through because the judge returned case materials to the department for rectification. Instead of releasing Denisov, the police kept him at the detention centre for another 24 hours.

- Traffic police officers played an important role in the detentions of protesters. We know of several such cases. The car of protester Yevgeny Lapshin was stopped by traffic police on his way to work. The man was escorted to a police department. When asked about the reason for the detention, the policemen answered: «You know it yourself.» Lapshin was detained pending trial. A similar case occurred with Ekaterina Skvortsova and Alexander (last name unknown), who were detained on October 21 by traffic police officers under the pretext of Ekaterina’s car having been seen at the protest motor rally on October 19. Both were forced to provide explanations at the police department.

- On August 5, police officers stopped a taxi that carried an activist Andrei Dudenok. He was dragged out of the taxi and put in a patrol car under the pretext of having participated in an «illegal event» on July 23. The police drew up a report charging the activist under Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offenses. It is still an open question how police officers learned that Dudenok was in that specific taxi.

- On October 15, police officers in Khabarovsk came to the Industrialny District Court to find a protester Ilya Merkulov and take him to the police department. Merkulov was at the court as a witness in the administrative case of another protester, Anastasia Subbotnikova.

The detainees were deprived of their phones or were not allowed to pick up their calls, as well as call a lawyer and human rights defenders.

In such cases, friends and family of the detainees who stop getting in touch learn about the detention by calling police departments and detention centres.

From police departments, the detainees are taken to detention centres and kept there until their trial.

During transportation, the detainees are often not allowed to use their phones, so relatives and defenders cannot find out where the detainee is.

Among the violations of detainees’ rights, keeping in detention centres until the trial is particularly prominent.

The detainees who have not yet been subjected to administrative punishment are placed in the same conditions as those serving administrative arrest.

Ekaterina Biyak, a journalist from Khabarovsk, told OVD-Info that at the beginning of the protests only the most «prominent» protesters were sent to detention centres until trial, however, by winter the majority of detainees have spent time in this centre.

ovsk, told OVD-Info that at the beginning of the proteThe detainees who have not yet been subjected to administrative punishment are placed in the same conditions as those serving administrative arrest.

sts only the most «prominent» protesters were sent to detention centres until trial, however, by winter the majority of detainees have spent time in this centre.

- On October 14, a participant of the Khabarovsk protests Stepan Yaryshkin was detained at his workplace and taken to a police department, where a report was drawn up. Before the trial, Yaryshkin was taken to a detention centre, where he was kept for two days until the court hearing.

- On October 30, a protester Anton Rybin was detained in Khabarovsk. He managed to send a message about his detention, then stopped getting in contact. Other protesters managed to find out that Rybin was placed in a detention centre. The staff of the centre said to those looking for the detainee that two reports had been drawn up, one trial had already passed and the second one would soon be held. Only two days later, the activist’s defender found out that Rybin had only one trial where he was arrested for seven days.

- On November 4, a protester and a journalist were detained in different locations in Khabarovsk. Both had their phones taken away and sent to a special detention centre. While the detainee was without means of communication, the police transported him from one police department, next to which a support group had gathered, to a different one.

- On November 7, journalist Yevgeniya Vazhenina was detained at the daily march. In a police department, the lawyer for «Apologia Protesta» Konstantin Bubon was not allowed to see her. She was taken to a detention centre without drawing up a report.

- On November 16, activist Vladimir Gretchenko was detained in Khabarovsk. He sent a message that he was being taken to the 4th police department, then stopped getting in contact. At the department, the OVD-Info lawyer Tatyana Titkova was told that Gretchenko was not there, and had not been brought at all. Later it turned out that at that time the activist was held in the police department. Later he was taken to a detention centre until trial.

- On November 26, archpriest Andrey Vinarsky came to a police department at the invitation of the security forces and stopped getting in contact.

Khabarovsk security forces have repeatedly used a special tactic against protesters and journalists. The activists call it the carousel: a series of several administrative arrests in a row. A similar technique was employed during the protests for the admission of independent candidates to the Moscow City Duma in the summer of 2019, when the inspirers of opposition rallies were placed under administrative arrests several times in a row, spending in isolation for up to 50 days.

In Khabarovsk Krai, in most cases it was ordinary protesters and media representatives who suffered from a series of arrests.

- Blogger Dmitry Khetagurov was detained on November 11 during the shooting of a single picket at the railway station. He spent the night in a police department, and the next day he was assigned a day of arrest (time served) and released.

-

While exiting the court, he was detained again, and the next day he was sentenced to five days of arrest.

-

At the end of his sentence, Khetagurov was detained at the door of a detention centre, put in a traffic police car and taken to the police department. But after about half an hour, he was released.

-

It turned out that law enforcement officers planned to give him a ride to get his belongings he allegedly had forgotten in the department, which were not actually there.

- On August 5, law enforcement officers opened a case against the active protester Andrey Dudenok. The court arrested the activist for five days. On August 10, at the end of his sentence, Dudenok was detained again until the trial. The next day, he was fined 10,000 roubles.

-

On August 15, Alexey Vorsin, the head of Navalny’s regional office, was detained and kept in the police department until the trial for two days.

Vorsin has repeatedly spoken at rallies with a loudspeaker.

- On August 17, he was arrested for 10 days. On August 25, at the exit of the detention centre, Vorsin was detained again until trial. On August 26, the court found Vorsin guilty under Article 20.2, paragraph 5 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (violation of the established procedure for holding a public event by a participant). The judge arrested the activist for 10 days.

Vorsin’s lawyer reminded the judge that this article does not provide for administrative arrest. The judge issued a ruling on correcting the «typo» and replaced 10 days with a 10,000 rouble fine.

- On October 15, in the headquarters of the Industrialny District Court of Khabarovsk, the police detained a protester Ilya Merkulov, who came to the trial of the administrative case of another activist. On October 22, he was detained at the exit of the detention centre, brought to court and assigned another five days of arrest.

-

The above-mentioned archpriest Andrey Vinarsky was assigned one day of administrative arrest after his detention. Immediately after his release, he was detained again and was again kept in a special detention centre until trial. On November 28, the court arrested the archpriest for three days.

OVD-Info is not aware of other law enforcement bodies except the police being used in order to pressure the protesters, as it was the case during summer 2019 in Moscow. However, the Khabarovsk authorities have expressed their intention to use this tactic.

In early November, social networks’ users discovered the minutes of the interdepartmental meeting debating the rallies, signed by the heads of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Investigative committee, the bailiff service, the Federal Security Service and the Prosecutor’s office of Khabarovsk Krai. The security forces did not deny the authenticity of the document. According to the document, the participants agreed to reinforce the administrative prosecution of the protesters, in particular, by bringing in the bailiff service.

In addition to the above-mentioned detentions at protests in support of Khabarovsk Krai in other regions, we’d like to focus on the case of a participant of the Khabarovsk rallies who got detained in the neighbouring region. Rostislav Smolensky is one of the prominent activists of the Khabarovsk protests and the driver of «Furgalomobile», a minivan that moved in front of the column during the marches. On November 10, 2020, Smolensky went to Vladivostok to collect signatures for Furgal’s release. He was detained and suddenly charged with public display of extremist symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses) because of an amulet in his car. The police thought it was the neo-pagan «Svarog Square'' symbol, which is used by the «Northern Brotherhood» nationalist group, recognized as an extremist organization and banned in Russia. The next day, molensky was arrested for 10 days. He filed the report to the prosecutor’s office, claiming that after his detention «drunken police officers» beat him and deprived him of food and of medical assistance. On December 21, it turned out that a criminal case for eabuse of authority had been open (Article 286, paragraph 3, item «a» of Russian Criminal Code).

The practice of dispersing assemblies or detaining and persecuting on a large scale, flagrantly violates the international human rights standards.

Administrative prosecution

Despite the fact that during months of protests in Khabarovsk Krai there were relatively few detentions at the events themselves, still the police drew up a large number of reports on the participants, who, in most cases, were detained days, weeks and even months after the events.

Once a decision has been made to open an administrative case against a participant of a rally, the police may invite the accused person to draw up a report, or come for them to their homes or workplaces, or even stop them at the street. For more details, see the section «Detentions in connection with the protests».

- At the end of July, Yevgeny Polishchuk from Nikolayevsk-on-Amur found out he was the subject of four administrative cases concerning the organization of an unauthorised rally (Article 20.2, paragraph 2 of Russian Code of Administrative Offenses.) In one of the cases, the evidence of his involvement was limited to a two-minute video showing him holding a loudspeaker, his words inaudible due to the noise of the fountain. In another case, the evidence consisted of the fact that he was waving at someone: the police thought he was directing the crowd’s movements. In the third case, Polishchuk drew attention because he was wearing a mask and sunglasses.

While it is not mandatory to be present in person at the drawing up of the report, and the police could just send a formal invitation to the procedure, it is still a common practice to bring people in by force.

- Police officers draw up standard reports against detainees. The reports contain a standard storyline of the offence made by a group which includes this particular «offender». According to lawyers working with OVD-Info, creating these reports is frequently accompanied by procedural irregularities: i.e., the address of the place where the offence committed is not indicated, or the name of the offender is wrong. Such violations sometimes make the court return the case file to the police for further processing or to dismiss the case altogether.

Charges

Most of the protesters in Khabarovsk Krai were charged with violations at public events (Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses). 489 cases were opened under this article between the beginning of the protests in Khabarovsk Krai and the end of November, 2020. There were 317 administrative cases under Article 20.2 in Khabarovsk, 110 cases in Komsomolsk-on-Amur, 13 cases in Amursk, 12 cases in Chegdomyn, and 37 cases in other towns of the region.

According to the data posted on the district courts’ websites, protesters in Khabarovsk Krai were mostly charged with Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1. The article provides for prosecution of «participation in an unauthorized assembly, rally, demonstration, march or picket which resulted in the obstructed functioning of critical city infrastructure facilities, transportation or social infrastructure, communication systems, movement of motorized vehicles and/or pedestrians, alternatively hindering citizens’ access to housing, transportation, or other social infrastructure», which is punishable by administrative detention for up to 15 days. This allows the police to keep the detainees in police departments (or even in special detention facilities) for up to 48 hours until trial. According to the courts’ websites, 312 cases were open under this part of the article.

132 cases were opened under part 5 (violation by a participant), 19 cases under part 2 (unauthorised protest organization), 24 cases under part 8 (repeated violation), and only 2 cases under part 1 (other violations by an organizer).

As we mentioned earlier in the section concerning detentions, in most cases the participants were prosecuted after the protests. The largest mass protests took place in summer, however, the most of the cases, 143, were opened in October. Significant numbers were also recorded in September (95 cases) and November (00 cases). The fewest administrative cases were initiated during the largest protests: only 82 cases were opened in August. During two weeks of July, 69 cases were initiated, since the filing process started only in the middle of the month.

Court Instances

Activists and defenders in Khabarovsk face the same problems during proceedings under Article 20.2 of Code of Administrative Offences as those in Moscow. During court hearings, judges usually reject motions, do not question police officers’ testimonies, ignore evidence submitted by the defence and only rarely acquit. However, Khabarovsk trials have some peculiarities.

Unlike Moscow, in Khabarovsk the police officers are significantly more often called in for questioning during trials under Article 20.2 of Code of Administrative Offences. Legally, one is allowed to question those testifying against them during a trial. In Moscow, the police officers are less likely to be questioned: judges tend to find the information contained in the reports and police testimonies in a case file sufficient.

- For example, on October 13, 2020, the Central District Court of Khabarovsk tried the case of Stanislav Kalinin, a protest participant. The police officer that detained him was invited to testify. The judge found his testimony contradictory. Besides, there was no additional evidence of Kalinin’s offence. He was acquitted due to the lack of evidence.

- One of the significant judicial features in Khabarovsk is the prosecution taking part in hearings. Under the Code of Administrative Offences, participation of the prosecuting party in the trial is not mandatory. Judges often use this to reject relevant motions of the defence. The ECHR has repeatedly pointed out to Russian authorities that denying to summon prosecution violates the right to a fair trial. For example, this is emphasized in the judgment on the Karelin v. Russia case. However, courts are reluctant to call up prosecutors or police officers that drew up the report of offence as the prosecuting party.

In Khabarovsk, though, this is a more common practice. Courts frequently grant such motions. Judges have called prosecutors on their own accord.

Sentences have their own peculiarities. As we have already mentioned, most cases were opened under Article 20.2, paragraph 6.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences. The punishment under this article can include a fine of up to 20 thousand roubles, community service, or administrative detention for up to 15 days.

Before protest events (which are usually held on Saturdays) judges sometimes impose several days' detention — apparently, to reduce the number of participants of the upcoming protest. Apart from that, courts sometimes do not distinguish between men and women or young and elderly people when imposing arrests.

- For example, the Central District Court of Khabarovsk imposed a week of administrative detention on Elena Donda, one of the participants. The same penalty has been imposed on Elena Slobodchikova, a retired woman, by the Industrialny District Court.

- Anatoly Dikunov, a 68-years-old retiree, was detained again immediately after having served four days in a detention centre. The police brought him to a department again and drew up a new report. They kept Dikunov at the police station for 24 hours until the trial and refused to let him see his son. At the trial, Dikunov was fined 5,000 roubles.

- Another one-of-a-kind situation happened in Khabarovsk when a court imposed administrative arrest on Alexey Vorsin, an activist of Navalny’s regional headquarters, although he was charged under Article 20.2, paragraph 5 of the Code of Administrative Offences, which does not provide for arrest. The defender pointed this out, and the judge retired to her chambers to «correct the typo». She then replaced ten days of detention with a 10,000 rouble fine.

-

The police came to Anton Dokuchaev, a student, at 7 AM. According to Alexey Pryanishnikov, Otkrytka Human Right Centre coordinator, Dokuchaev was brought from his dormitory to a psychiatric hospital for a mental health examination within the frame of his administrative case investigation, The judge has questioned Dokuchayev’s sanity because of his speech impediment.

-

In most cases where decisions have entered into force, protest participants have been found guilty. Some detainees did not appeal such decisions. When passing judgements, courts referred to the lack of reasons to distrust the police officers’ testimonies. The prosecution’s evidence rarely got proper legal assessment. Defence motions were denied, witnesses for the defence were not called, photo and video evidence was not appended to caseד. Such practice is common not only in Khabarovsk, but all over Russia.

Criminal prosecution

According to present knowledge, four criminal cases associated with protests in Khabarovsk Krai were opened. Attorneys working with OVD-Info provide legal assistance to the accused in three of them.

The case on repeated violation of an established procedure for holding a public event (Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code)

The defendant: Alexander Prikhodko.

This case was opened on October 12, 2020. The grounds for it was Prihodko’s detention during a protest on October 10, which was brutally dispersed by the law enforcement officers.

Charges under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code can be brought if a person has already committed more than two offences under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses over the past six months. Prikhodko has four such offences, for rallies held from August 16 to 19.

Prikhodko’s case was the ninth one under Article 212.1 since its introduction to the Criminal Code.

Prikhodko signed an undertaking to appear at the interrogations as a measure of procedural compulsion. Attorney Andrey Bityutsky working with OVD-Info represents his interests.

It should be noted that many residents of Khabarovsk Krai regularly appeared at rallies (which the police regard as a violation). So it is not surprising that several active protesters already have more than two court decisions under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses, including those that have entered into force.

At the end of October, the regional court overturned the decision to arrest Dmitry Fedoseev, a Komsomolsk-on-Amur resident, stating that the first instance court did not assess the evidence of the elements of offence under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. Besides, back in September, this article was mentioned in a similar decision of the regional court regarding Valentin Kvashnikov, a Khabarovsk protest participant.

In December, it became known that the police started a pre-investigation check under the same article regarding another participant of the Khabarovsk rallies, Valery Skripalshchikov.

Cases on the use of violence against representatives of power

Denis Posmetyukhin’s case

On September 25, 2020, police and bailiffs were going to arrest «Furgalomobile 2.0», a minibus frequently seen at Khabarovsk rallies, for the debts of its driver’s wife who owned the car. The bailiffs and police officers tried to force the driver, Andrei Maklygin, out of the vehicle, while the activists stood around the car. They had a disagreement, during which one of the participants used pepper spray.

In the wake of the conflict, a case on the use of violence that does not endanger human life or health against the representative of the authority (Article 318, paragraph 1 of Russian Criminal Code) was initiated against activist Denis Posmetyukhin. According to the Investigative Committee, it was he who used the pepper spray. Posmetyukhin was sentenced to a year of penal colony and is currently serving his term. He was represented by attorney Aleksey Petrenko working with OVD-Info.

Anastasia Subbotnikova’s case

In the wake of the above-mentioned forcible dispersal of the rally on October 10, a criminal case was opened against one of the participants, Anastasia Subbotnikova, under the article on the use of violence that does not endanger human life or health against the representative of the authority.

The case consisted of two episodes, in both of which Subbotnikova was accused of hitting the policeman twice in the face. She said she was only trying to remove the masks from the faces of the plainclothes men who participated in the detention of the protesters.

Subbotnikova is under a written undertaking not to leave her place of residence. She is represented by attorney Alexei Petrenko working with OVD-Info.

Nadezhda Kochetkova’s case

Another case was initiated in connection with the violent dispersal of a rally on October 10. Details are unknown. Kochetkova is represented by a court-appointed lawyer.

Other cases (unconfirmed information) and inquiries

In November, 2020, the minutes of an interdepartmental meeting regarding rallies in Khabarovsk Krai leaked to the social media. According to the document, a case on public appeals to the performance of extremist activity (Article 280 of the Criminal Code) has also been opened. Allegedly, someone on the Internet called for the use of violence against the security forces. However, no details have yet been clarified.

The same document also mentioned a statement of a woman who was allegedly by unidentified participants of «illegal rallies».

It is also known that a pre-investigation check was launched against the driver of «Furgalomobile 2.0», Andrei Maklygin, under Article 319 of the Criminal Code (public insult of a representative of the authority). According to security officials, Maklygin insulted a traffic police inspector, who demanded to show him papers on the car.

An inquiry under Article 318 of the Criminal Code (use of violence that does not endanger human life or health, or threats to use violence against a representative of the authority) is being conducted against a protest participant, Yevgeny Lapshin.

The dvhab.ru reported that criminal cases were also opened against the police officers who tried to arrest «Furgalomobile 2.0» in late September. Information on the progress of this case proved unavailable. Besides, it is known that the Investigative Committee of the region refused to open a case on the beating of Yevgeny Dilman, a participant of the rally on July 29 in Komsomolsk-on-Amur. He and eyewitnesses said that the police knocked him to the ground, beat him, and used a submission hold against him.

Use of violence against a representative of the authority is prosecuted under Article 318 of Russia’s Criminal Code. Pursuant to the first paragraph of this article, the use of violence that does not endanger human life or health is punishable by deprivation of liberty for a term of up to five years. The second paragraph determines the punishment for the use of violence endangering the said representatives’ lives or health (deprivation of liberty for a term of up to 10 years). The problem is that the protesters are prosecuted under this article even when police officers have been barely touched, when a paper cup was thrown in the direction of the police, or when a person involuntarily fell down on police officers. Moreover, according to the Novaya Gazeta’s investigation based on the analysis of 12 thousand available court rulings under Article 318, paragraph 1, the punishments for the participants of public assemblies were stricter than in other cases (for example, in case of a policeman hurt in a domestic conflict).

Other Methods of Intimidating Protesters

Participants of the actions in support of Sergei Furgal in Khabarovsk Krai have also had to face extrajudicial pressure: surveillance, warnings, police visiting their houses, threats of administrative and criminal prosecution.

- In July, traffic police threatened Rostislav Smolensky (Buryak), the driver of the so-called «Furgalomobile» (a minivan decorated with banners in support of Furgal) to impound and arrest his vehicle for an unpaid traffic ticket. His driver’s license was temporarily taken away, the truck itself was blocked by police cars. When the other protesters stood up for Rostislav, the police agreed to give him back his license and let the truck go.

- In Осtober, Diana Luka, a Khabarovsk resident who participated in the protests, was twice visited at her workplace by a plainclothes person. He claimed he was a police officer and demanded that she go with him to the police station. He did not give any solid reason for that: instead of producing his police certificate, he showed her his passport. He evaded direct questions, referred to an unidentified case, and asked questions like «If you knew tomorrow you had to face arrest, prison and death, what would you change in your life?» During the second visit, he was accompanied by another man who made a video recording.

- In November, Anastasia Savchenko, resident of Pereyaslavka village, received a notice of inadmissibility of participation in unauthorised rallies. It happened after she held a single-person picket in support of Furgal. The morning after the picket, the police came to her house and demanded that she go with them to the police station to be issued the notice.

- Anatoliy Dyakunov, a participant of Khabarovsk’s protests, was visited at his home by the officers from the Centre for Combating Extremism. They refused to identify themselves, issue summons or explain the reason for their visit. According to eyewitnesses, they pounded on the door for more than an hour and cut off the apartment’s electricity.

- A protester Ekaterina Utkina was visited by the police at her home. They were knocking on her door and demanding that she proceeds with them to the police station, where a case file would be compiled. It was not their first visit. During the earlier visit, the officers wanted to escort Utkina to the police station in order to question her as a witness to an unidentified criminal case. The officers wore plain clothes; they neither gave her any details of the case concerned nor showed her any supporting documentation. According to Utkina, they called her on the door phone and threatened her trying to coerce her to leave the flat.

- According to the statement of Mikhail Degtyarev (then interim governor of Khabarovsk Krai), made on July 28, the protesters have been tracked. «There is surveillance, a system which includes face-recognition technology is at work, » he said.

In one incident, police officers took an activist to a psychiatric hospital.

- On October 19, 2020, Anton Dokuchaev, a student who participated in the protests, received a call from a police officer, who demanded from him to come to a psychiatric hospital the following day. The reason was not explained, but Dokuchaev was threatened with «serious trouble» if he did not comply. Early in the morning on November 10, police officers came to Dokuchaev’s dormitory accommodation to escort him to a medical examination aimed at establishing whether he was sane. According to the Open Russia Human Rights Team, the judge in the administrative case against Dokuchaev requested this examination as part of the proceedings. According to the lawyer, the judge decided to request the medical examination because of Dokuchaev’s speech disorder. The hospital refused to conduct the examination, and let Dokuchaev go home.

Forced quarantine has also been used as a means of pressure. The Open Russia employees faced it when they came to Khabarovsk in July to participate in the protests and collect signatures against amendments to the Constitution.

- On the morning of July 25, when the Open Russia employees arrived in Khabarovsk, police came to the hotel where they stayed. Police officers claimed that the activists had been exposed to a person with known COVID-19. Therefore, they had to be placed into an observation facility for two weeks. Police detained Denis Ibragimov, «Open Russia» coordinator from Chelyabinsk. He was put under quarantine in the «Tourist» hotel and was unable to join the protest. Only on the following day, July 26, Ibragimov managed to get tested for COVID-19. After he received a negative test result, Ibragimov was released. He filed a motion requesting to recognise his forced quarantine as unlawful, but in August, the court dismissed it. During the proceedings, Ibragimov’s lawyer found a letter attached to the case file from the Federal Security Service to the Russian Agency for Health and Consumer Rights. It stated that Ibragimov had allegedly been exposed to a person with known COVID-19. It was also noted in the letter that Ibragimov was an Open Russia member.

There are documented cases of the use of force against protesters, and not limited to detentions during rallies at that.

- On November 20, Evgeniy Mazikin, a protester, was attacked by two unknown men, who called themselves police officers. According to the activist, the attack happened next to a shop in the Yuzhny residential neighbourhood in Khabarovsk. The attackers got out of the car, ran up to Mazikin, beat him, and shot him several times with a traumatic weapon. Mazikin linked the attack to the increase in pressure on the protesters before another rally.

- There were separate cases of conflicts during the rallies. In one case, an instigator attacked the protesters; in another, several vehicles attempted to drive into the crowd.

-

Unlike the situation in Moscow after the protests of summer 2019, we are not aware of any cases of mass dismissals or expulsions from educational institutions, or of any such threats to participants of Khabarovsk protests. OVD-Info is aware of only one case of employment termination as retaliation for participation in Khabarovsk protests. Besides, there was one case of dismissal of a public official who spoke up in support of the protests.

At the beginning of September, Mikhail Degtyarev, then interim governor of Khabarovsk Krai, fired Andrei Petrov, deputy head of the forestry management office. The latter previously posted a video statement in support of Sergei Furgal where he also stated that «no one notices» participants of the protests that by that time had lasted for more than a month. He also advocated making Khabarovsk Krai a republic. «That’s pure extremism. The weirdo lives off the state, but starts advocating for separation of Russia’s region. Everything is officially recorded. What is in his head?», Degtyarev commented during a live stream. Petrov emphasized that he never called for separation of Khabarovsk Krai from Russia. «By the logic of the incumbent administration, public officials are not allowed to criticize it, » Petrov stated.

Threats of dismissal were used to pressure the journalists who covered the protests in Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krai. For more information, see the section «Shaping of an official narrative on Khabarovsk protests».

Children’s services have also been involved in pressuring the protesters.

- On December 12, the police came to Tatiana Ovechkina, a protester. They took her to the police station to draw up a report of repeated violation of the established procedure for holding public events, in connection with a rally that took place the previous week. Soon, Children’s Services officers visited herThey wanted to know who watched her three children when she left to participate in the protests. They also summoned Ovechkina for an additional talk on December 14, the same day when she had a hearing of her case at the Central District Court. In the morning, the hearing was postponed for an indefinite period, but the same evening she received a phone call summoning her to court.

Just like in Moscow, Khabarovsk official media reported an admittedly lower number of protesters compared to the estimations of independent journalists who attended the demonstrations.

- On July 11, the Main Directorate for Internal Affairs in Khabarovsk Krai announced that 10 to 12 thousand people attended «the unauthorised public assemblies organized by Furgal’s team.» The Khabarovsk Krai Today media outlet wrote that the number of people present at the demonstration exceeded the number of participants of the Bessmertny Polk march, that was attended by up to 60,000 people.

- On July 18, the city administration reported that 10,000 people participated in the rally; on July 25, they reported 6,500 participants. According to the estimates of the Meduza reporter, the event of July 25 was larger than those of July 11 and 18 by one third; several tens of thousands of people participated in the rally.

The official media put a negative spin on the protests: they suggested the protesters supported Furgal’s «criminal past» and intended to provoke public order disruptions and clashes with police; contemplated that «foreign interference» and «instigators» were at work; and insinuated that people were paid to participate in rallies.

- On July 17, a TV programme on Russia 24 channel about Furgal’s case did not cover protests directly but speculated that «those wishing to skim the cream off the protest moods are not afraid of the bloody trail.» The presenter said, «Various representatives of organizations recognized as undesirable have already tried to use the detention of the governor for their own purposes. For them, the main things are pogroms, riots and clashes with police.»

These talking points were repeated almost word-for-word in a criminal news broadcast on July 18:

- «Despite the evidence of Furgal’s involvement in a murder, some of his supporters said they were ready to support the governor, even with a criminal past. The situation proved useful to various instigators and bloggers, who immediately came rushing up to Khabarovsk.»

Both broadcasts claimed that, according to «certain information», the bloggers had been under the influence of an organization «controlled by the US State Department»: «Its main goal is to stir up a storm and report it to its Western patrons.»

- Compared to these wordings, the discussion of the Khabarovsk events on The First Channel in the Vremya Pokazhet programme of July 17 looks more neutral. But here, too, the presenters emphasized that protesters’ demands were «unclear, ” the protest was «well organized» and «could have been organized by forces close to Furgal that possess sufficient material resources», «stool pigeons» had infiltrated the protests, and rallies had been organized using certain «technologies»: «people appeared handing out posters and leaflets with instructions to the participants.»

- Sergei Kravchuk, the mayor of Khabarovsk, noted on July 17: «During the recent rallies we have been seeing the same faces, who shout the same slogans and behave inappropriately. They are clearly working for money.» The next day, Kravchuk explained that he had not meant all the participants of the rallies, but separate persons who had arrived in Khabarovsk with a specific purpose. «During the recent days, inadequate, aggressive people have appeared here. The word on the street is that they are not locals, but visitors from other regions. There are about 20-30 of them. They spur the activity of the public, shouting out previously prepared chants. They work for money, ” he said.

- According to Meduza, Vladimir Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov, in an interview on July 23, explained the protests as an «emotional reaction» to the governor’s arrest. He called the protests «a mainstream trend for representatives of a would-be opposition, who are not reluctant to make a little noise, trying to earn some points on this situation.»

- On July 24, Mikhail Degtyarev, the then interim governor of Khabarovsk Krai, said that foreign citizens were involved in the organization of the protests in Khabarovsk.

-

«I can understand the large rallies that began after the arrest of Sergei Ivanovich [Furgal], they are spontaneous. It was bitterness and anger of the Khabarovsk people for their elected governor, ” Degtyarev asserted, answering a question from BBC Russian Service. «But I have irrefutable data from the law enforcement agencies about who organizes all this and how. It is investigative information <…> These are Khabarovsk residents for the most part, but there are many non-residents, and there are several foreign citizens.»

A reporter asked how any foreigners could get to Khabarovsk while the borders were closed. Degtyarev answered, «Do you think there are no foreign citizens in Russia now? There are. Some stayed in Moscow to organize rallies and riots there. The borders had closed — they stayed there. An opportunity appeared to stir things up in Khabarovsk Krai — they flew here. After all, our transregional communication lines continue to function.»

- Yelena Greshnyakova, a member of the Federation Council for Khabarovsk Krai, told the protesters that the claims about foreign involvement in the organization of protests are «nonsense». «There is no trace of foreign interference. The presence of representatives of foreign states covering events is one thing, while the organization of the protests is an entirely different issue. In my opinion, this apparent self-organization of the masses is a result of our common tragedy, ” she said on August 8. «I felt indignant at how some presenters at federal channels characterized protests and their participants. We are all taxpayers, and since these are national channels, then they must cover the matter without bias, ” Greshnyakova said.

- On July 27, Degtyarev reported that «several knives» and an axe were confiscated from the protesters on the previous weekend.

- In October, in an interview for Znak.com, Degtyarev mentioned that the residents of Khabarovsk allegedly complained about the protesters.

-

«These protests do not interfere with my work nor with the work of the government of Khabarovsk Krai. It only bothers the city residents, and they complain. I am asked at all my public meetings: ‘When will you shut them down? ’» In the same interview, Degtyarev claimed that the «street opposition is usually financed from abroad, or by certain offended oligarchs.»

Since the beginning of the protests, it has become known about the pressure on official media. The employees were threatened with employment termination (as in the above-mentioned case, when the authorities of Primorsky Krai made demands to journalists) or criminal prosecution.

- On July 12, Yuri Trutnev, the Presidential Plenipotentiary Envoy to the Far Eastern Federal District, arrived in Khabarovsk. As Meduza reported citing unnamed sources from the regional government, Trutnev was «very dissatisfied» with the information policy and work of Furgal’s press service. «I told them: should you organize rallies, I guarantee you will be heaping up trouble for yourself. By defending the governor, you are starting a war. The main idea was that rallies should be stifled, ” allegedly said Trutnev. Another unnamed source close to the envoy’s office confirmed that the envoy indeed considers the administration’s press service the «instigator» of the protests. Meanwhile, on July 10, on the eve of the first protest action, the Sergei Furgal Instagram account (the main media resource of the press service) stressed that the press service did not гкпу people to participate in unauthorised events, and reminded of possible administrative liability. «Your inclination to come out even to spontaneous events is humane and inspiring. However, we are not calling on anyone to do this. We do not want anyone to get hurt. We cannot go out ourselves because then we will most likely be deprived of the opportunity to inform you, ” their post said.