Publication date: 04.08.2023

Activists started to be sentenced in the second month of the full-scale invasion, mainly participants of mass anti-war protests in the first days of the full-scale invasion. As of 12 July, we know of 215 sentences, 82 of which carry real prison terms. 3 cases were dismissed.

We are taking into account all sentences in «anti-war» cases except for those handed out for draft dodging or for allegedly trying to defect to Ukraine’s military.

We include the following under "real prison terms" in the chart: imprisonment in a penal settlement, a general regime penal colony (including in absentia), a strict regime penal colony, compulsory medical treatment, as well as cases of imprisonment where the strictness of the institution's regime is not specified. We include the following under "other types" of punishment: fines, restrictions of freedom, suspended prison sentence, compulsory or corrective labor, including suspended punishment, as well as community service. As shown in the data, real prison terms were initially less frequent but have started to increase at the start of 2023, eventually surpassing other types of punishment.

In the chart below, sentences in "anti-war" cases are broken down by type of punishment.

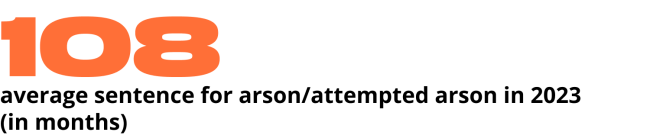

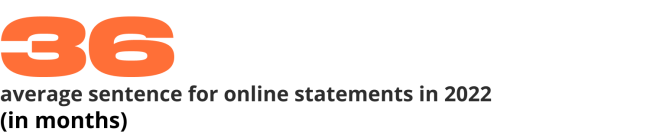

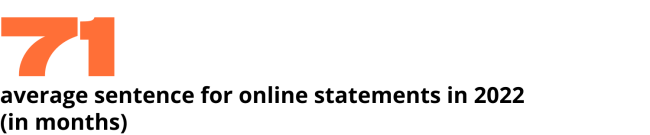

The average sentence is the mean of all the sentences with real prison terms handed out in the respective month. This number has also grown over time.

The difference in the average sentence and the number of sentences with real prison terms between 2022 and 2023 is equally clear. However, it is important to note that we are comparing uneven periods - 9.5 months in 2022 and 7 months in 2023.

The statistics include different actions and different charges, but what all of these cases have in common is the anti-war stance of the defendants as the basis for prosecution.

At the same time, it is difficult to assess whether the overall level of repression is increasing on the basis of graphs alone - an increase in the number of convictions only means that cases that were actively prosecuted in the first months of the invasion are coming to an end.

It is also important to remember the individual nature of each case and investigation - many factors simply cannot be taken into account in this kind of study. For example, the lack of a good lawyer may lead to a more serious charge and a longer sentence on the one hand, and on the other hand, to a plea of guilty, a special trial and a lighter sentence. In addition, the severity of punishment is influenced by other mitigating or aggravating factors - for example, dependent children, past convictions of the defendant and even the personality of the investigator. Some of these factors affect not only the punishment, but also the speed of the investigation.

Moreover, the increase in time limits is also explained by the changing nature of the protests - the actions of the defendants have changed, arson attacks on military commissions and other administrative buildings are more frequent, and cases of damage to railway infrastructure and calls for such actions are appearing. The regime has responded accordingly, resorting to violent means of repression.

Actions

Forms of resistance change over time. Russian society's first response to the war was spontaneous mass protests that were suppressed by security forces. Then the protest transformed - unable to participate in collective action legally, people began to express dissent in other ways: single pickets, anti-war writings and statements, and the destruction of patriotic symbols. Later, direct violent actions spread.

Articles

How actions were qualified to determine the severity of punishment is no less important. For example, in 2022, defendants in "anti-war" cases received numerous verdicts under Article 214 of the Criminal Code for vandalism, with a maximum punishment of up to three years of imprisonment. Such cases were mainly brought against authors of anti-war inscriptions and graffiti, as well as individuals who destroyed patriotic symbols.

In 2023, the number of verdicts for "vandalism" noticeably decreased, but the number of verdicts under Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code related to spreading fake information about the army (punishable by up to 15 years of imprisonment) and Article 280.3 about repeated discrediting of the army (punishable by up to 5 years of imprisonment) as well as "terrorist" articles increased.

It is worth noting that there are cases where one person is charged with multiple articles or multiple episodes under the same article. Additionally, in some cases involving anti-war actions, other elements are combined, such as statements on different topics. It is essential to keep this in mind when drawing conclusions about the principles of sentencing.

Certain actions frequently seen in "anti-war" cases will be examined separately and in detail.

Arson incidents

The increase in the average sentence can be attributed to the rise in the number of direct action events, such as arson of military enlistment offices and administrative buildings, and sabotage of relay cabinets on railways.

In the beginning of the war, arsons of military enlistment offices and administrative buildings were primarily classified under Article 167 of the Criminal Code (intentional destruction of property), which carried relatively minor punishments. However, in 2023, similar actions were more frequently qualified as terrorism or sabotage articles, which carry significantly harsher penalties. For instance, in the case of Kirill Butylin, the initial accusation for arson was under Article 167 — his case, one of the first in connection with the arson of a military enlistment office, was initiated in March 2022. Later, the charge was reclassified under Article 205 of the Criminal Code (committing an act of terrorism).

Social media posts

Despite the increase in arson and sabotage court cases, online statements remain the most common reason for prosecution. 88 out of 228 verdicts were related to posts on the internet. The severity of punishment has also noticeably increased compared to 2022, while the charges are usually the same.

In some cases included in our statistics of prosecutions for online posts, there are additional charges besides the ones for expressing opinions. For instance, Kirill Butylin is also accused of arson, while Bogdan Ziza is accused of vandalism by pouring paint over an administration building. This has affected the average sentence for online statements, which, without these two cases, stands at 67 months in 2023.

At the same time, we can not state that in 2023 real prison terms are uniformly handed out for online comments - for example, Ivan Kavinov was sentenced to 3 years in prison for posting "deliberately false information," while Diana Nefedova received 6 months of corrective labor for a similar offense. Since the beginning of the conflict, out of 76 verdicts for online posts, only 32 have resulted in real prison terms.

This is also explained by the difference in case qualifications - in Ivan's publications, the law enforcement officers found a motive of 'political hatred,' so he was charged under Part 2 of Article 207.3, while Diana was charged under Part 1. We do not know for certain what the investigator relies on when qualifying the charges in such cases.

Although Part 1 of Article 207.3 potentially allows for imprisonment for up to 5 years, in practice, the actual sentences are much less common compared to those given under the second part.

The overall statistics do not include persecutions for attempting to join the armed forces of Ukraine, the "Russian Volunteer Corps," or the legion "Freedom of Russia," or for refusing to fight on the side of Russia. Such cases fall under the category of "anti-war cases," but primarily those where evidence falsification can be mentioned.

Convictions for refusal to fight or desertion are placed in a separate category. There are many such cases, and apparently not all of them are related to openly expressing anti-war motives. However, we consider that when a person expresses a clear unwillingness to participate in the war on Ukrainian territory, we can include such persecution in the "anti-war cases."

Of course, persecutions for such action (in a way, for inaction, for refusal to act, but coupled with an expression of position) significantly differ from other types of persecutions. Nevertheless, we view this form of resistance as essentially anti-war.

We are aware of 11 convictions for such cases, out of which 9 resulted in actual imprisonment.

Conclusion

The most common form of anti-war resistance remains the public expression of opinions - online, through slogans or stickers, or verbally.

At the same time, there is an evident transformation of protests into more violent forms of resistance unusual for Russian realities, such as sabotage and arson. The authorities utilize the most uncompromising means of suppressing such protests. This partly explains the increase in average sentence length and the overall number of prison sentences.

The severity of punishment varies greatly depending on the case qualification, the principles of which are often unclear - for roughly the same actions, one can receive sentences ranging from 4 months to 19 years. This creates an additional intimidating effect: people who disagree with the war are afraid to express their opinions because they do not fully understand what punishment may await them for their anti-war activities.

The data which this study is based on can be found here.