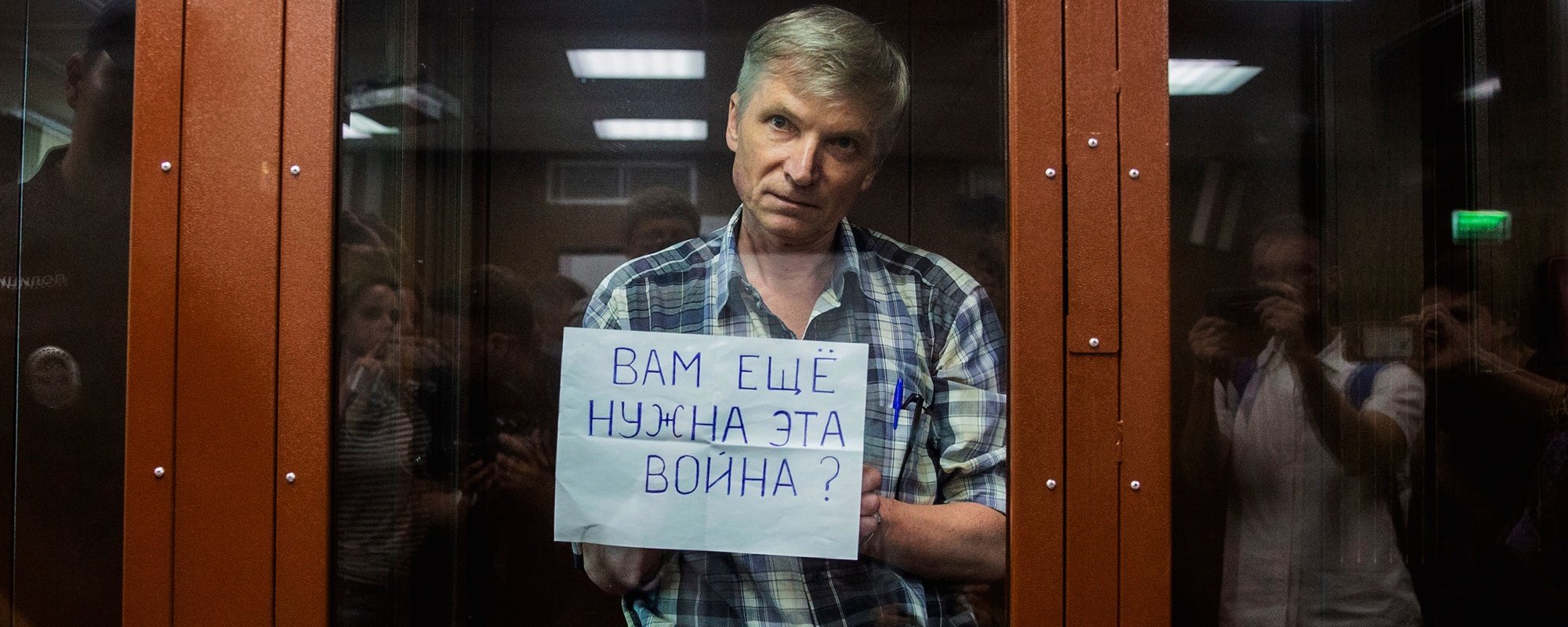

Moscow municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov was sentenced to six years and 11 months in prison for the anti-war statement he made during a council meeting. Gorinov proposed to suspend district holidays while children are dying in Ukraine. At the request of OVD-Info journalist Ilya Azar entered into correspondence with Alexei, what follows is the conversation between two former municipal deputies.

— Tell us more about your health. [It was] reported that you had tuberculosis. Is it true that you refused to go to the hospital? Why?

— [I] don’t know who writes what about tuberculosis. Some nonsense. [It is] my bronchi tha are actually weak but it is nothing. In the pre-trial detention I came down with bronchitis, when there was almost nothing there to treat it. For more than two weeks I did not receive the necessary medical care, so my physical condition worsened every day. I was willing to accept any option, just to recover. Anna Karetnikova helped me out, she passed me the necessary medicine through the detention center doctor. In a matter of days colour returned to my face.

— I read that you are outraged by how the medical care is provided — or rather is not provided, in pre-trial detention. Neither for you, nor for your cell mates.

— I am not so much outraged. I am downcast. As long as government takes on the burden of confining [its] citizens, medical services in places of detention should be the best in the country. Because a [detained] person has no opportunity to provide himself with the necessary medical care, even at his own expense.

Detainees here have various chronic diseases, there are people with disabilities, while many simply fall seriously ill, having been imprisoned for several years and awaiting the end of the investigation and trial. Businessmen accused of fraud suffer the most. Many, if not most, of them do not belong here. My cellmate has been trying to get a dentist appointment for several months.

Recently another «fraudster» has been moved into our «apartment». He has a group II disability with a spinal fracture caused by a car accident. [He is] bent over [when he] walks. While he was being transferred from Stavropol, where he spent more than a year in a pre-trial detention center, he picked up some sort of scabies. It seems to me that he should have been examined by the relevant specialists as a priority. But it didn’t happen…

It is, of course, necessary l to create a full-fledged medical service attached to the Federal Penitentiary Service. After all, a significant part of Russia’s population is contained here. Judging by the scale of the hostilities that our state is conducting, funding for such medical service could be found.

I would have changed a lot here both as a manager, and as a lawyer.

— Tell us about the detention center. Who are your cellmates?

— The detention center is overcrowded by 20-25 percent. When I just «checked into» Matrosskaya Tishina, we had four bunks for seven people. According to my estimates, more than a half of the people confined in pre-trial detention facilities are charged with drugs (Article 228 of the Criminal Code of Russia) and fraud (Article 159 of the Criminal Code of Russia). Many are imprisoned for several years pending the end of the investigation and trial. I have seen a detainee who has been waiting this way [imprisoned in a detention facility] for six years.

[They] do not allow prisoners to remain in the same company [in the cell] for too long. Prisoners are mixed around, moving from one prison cell to another. That’s how I, for example, have already changed the fourth «hut». Every time you have to get used to new people, find a common ground with them, adapt to new living conditions, which in different cells may differ from each other. All of my current neighbors are charged with fraud. Criminal charges against two of them are based on complaints by ex-partners, although the reasons themselves are fabricated.

Both in the current and in the previous prison cells, Putin was criticized and even (!) scolded by almost everyone. Every person has their own motives and complaints. Many people remain silent about the special military operation, avoiding direct assessments. So far, I know only one person who fully supports it. Others do not understand what all this is for.

— What do they think about the «special military operation» and Putin, about your sentence?

— Many in a way «rediscover» Russia for themselves after they first encounter the Investigative Committee, the prosecutor’s office, the judicial system, the Federal Penitentiary Service. They remember some mythical human rights activists who «for some reason are inactive». When they realize the hopelessness of their situation, they begin to live in hopes of an amnesty or mitigation of the expected punishment by the amendments to the Criminal Code supposedly in preparation.

Prisoners, including those from other cells, who know about my case, are confused not only by [the length of my] term of imprisonment, but also about the fact that my statement, my opinion can even be a reason for a criminal case to be initiated.

Seven years in prison for an opinion

— What do you make of a month’s reduction to your term [of imprisonment]? [Do you consider it] mockery? Did you hope for a more significant [sentence] reduction or an acquittal?

— [I] consider it an advertisement [trick], when instead of a price of 1000 rubles the label indicates only 999. It is not the reduction of the term itself that is a mockery, but the initiation of a criminal case, its hearings in court and criminal conviction for three phrases about the fact that a war is taking place, that children are dying and that hostilities must be stopped. That is, for what TV hosts, political scientists and other experts are now openly discussing on propaganda state channels. Otherwise, of course, mockery of the legal system is obvious.

I had no illusions about an acquittal or a reduced sentence in the court of appeal. This is not what the authorities came up with all of this for. My criminal case under this article is one of the first in a series of similar cases. Firstly, it serves to intimidate other citizens, and secondly, as a guideline for judges when they sentence other defendants in equivalent cases.

In such a legal system where it would be possible for me to be acquitted, such an article could not even appear in the Criminal Code.

— When you said at a meeting of the council of deputies of the Krasnoselsky district [of Moscow] that it is inappropriate to hold a children’s drawing contest, while there is a war in Ukraine and children are dying [there], did you think about the possible consequences? Were there any thoughts of remaining silent or speaking euphemistically?

— Everything I said at a meeting of the council of deputies of our municipal district was said within the scope of my routine deputy activities, my authority as a chairman of the social commission. Obviously, I did not think of any adverse consequences for myself, or that what I said was a crime. After all, I only mentioned that a war began with a neighboring state, reporting freely available information about children’s death, and expressed my opinion on the need to stop hostilities. Nothing more.

— After [State Duma deputy from «United Russia» Aleksandr] Khinstein filed a criminal inquiry with the Investigative Committee against Elena Kotenockkina, [the head of the municipal deputy] council of [Krasnoselskii] district and she left the country, did you think of doing the same?

— I do not follow what Khinstein and similar characters do. And I was not following how the events associated with this case developed.

I was not at all aware that anything dangerous for me was happening around our ordinary deputy council meeting. I learned about all this fuss, the complaints from Khinstein and others, after my arrest. Because I was completely absorbed by the subject of war, following events taking place in Ukraine very closely. Besides, I am a professionally employed person as well as a municipal deputy. The only thing I noticed the day before my arrest was two young men who looked like operatives standing outside of my house in the morning and watching me get into the car.

That Elena Kotenochkina, [who was] on vacation, did not return to Russia, I found out [only] in the Investigative Committee where I was brought for questioning on the day of my arrest. I am glad she was able to do so and hope she is safe. Maybe she will read this interview. I would like to take this opportunity to tell her I am grateful for our collective work to which she devoted herself for all five years. She was the most dedicated and efficient member of our team.

— In court you said: «They took my spring, they took my summer, and now they have taken 7 years of my life.» Alexei Navalny has presidential ambitions and believes he won’t have a claim to power in the future if he stays abroad. Ilya Yashin, who is young and full of energy, seems to think the same. Why didn’t you leave?

— Ilya Yashin is a real hero. He had told me before that he would not leave Russia under any circumstances. Vladimir Kara-Murza when I asked him a similar question as we briefly crossed paths in a police van said this: «I consider myself a Russian politician and therefore, I must be here now, in Russia.» In my eyes, he is also a heroic character, just as Alexei Navalny.

I am not among the leaders of the political opposition, I don’t have any personal political ambitions. My mission is different. Because of that, I did not need to go anywhere. I didn’t have a reason, a motive [to leave]. Nobody persecuted or threatened me, there was not even a hint of any danger up until my arrest. I still wonder why the authorities, in the form of law enforcement, would suddenly harass me. And with such frenzy.

— It seems that the «This is my country, let them leave» principle is right and beautiful, but is such strict adherence to principles worth prison time? You can do more as a free man. Not to mention [your] family.

— Personally, I did not have a choice to leave or be imprisoned. No one asked me or made me any offers. And I did not commit any crimes to think of such questions preemptively or afterwards.

— What do you think of those who left? Is it cowardice? What is more right: to stay and be silent; stay, be vocally opposed and imprisoned; leave and be vocal?

— To speak and not be imprisoned is better. But, in Russia, it seems that is no longer an option. If you are a politician or a civil rights activist, who intentionally stayed in our country then, of course, you should not be silent. Otherwise, what is the point of being here if you can leave and safely organize from abroad? Of course, you have to think about your safety and the safety of your loved ones, and in case of a threat it is better, if possible, to leave. I say this out of humanitarian consideration.

And I don’t have any moral authority to judge anyone who’s left Russia due to the ongoing events.

— Do you think that such a harsh sentence for you and the fact that now three people in Krasnoselskii [district municipal] council have been charged with criminal [offenses] is linked to Ilya Yashin’ activities?

— I do not have an extensive answer to this question. In 2017 we won municipal elections in Krasnoselskii district as a cohesive team from the «Solidarnost» movement. We are all different, complicated people but Yashin could unite us, inspire us, and set our target for victory. He was our team’s motor in the election campaign and further work. I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with such a bright personality.

I personally pose no threat to the political regime or its stability. But I am sure of one thing: if we ran again as a team this year, in free and honest elections, then we undoubtedly would have a convincing victory even without Ilya, who is still subject to anti-constitutional restrictions on passive suffrage, prohibiting him from running for office.

— After sentencing, you told the judge: «I am surprised, why so few [years].» How is it that in Russia one can be sent to prison for 7 years for [expressing] an opinion?

— Because that is how it has been in Russia for the last several hundred years. It is not sudden. There have only been short breaks associated with the change or overwhelming of the power. We are still walking in circles. And we can’t say that our people haven’t paid enough for freedom in the last century. I mean the Civil War, collectivization, Stalinist repressions, WWII, dissidentship, defence of the White House in 1991 and 1993.

And what is happening now — it is quite natural for the country’s established political regime. My colleague at that very meeting of the deputy council gave this regime her own assessment (Kotenochkina then called Russia a «fascist state» — OVD-Info).

— Investigation claims that you and Elena Kotenochkina «entered into a premeditated criminal collusion», «distributed criminal roles amongst yourselves» and «developed a general plan for committing a crime.» How can this even be said seriously?

— You shouldn’t talk about this seriously. But you can joke and laugh about it. This wording is written into the guilty verdict, however premeditated collusion specifically was not the subject matter of the hearing. No evidence of it was presented by either investigation or prosecution.

Evidently, such a qualifying feature was added by the investigation and stamped by the court to make the punishment more severe, although it is not clear what for. In appeals, the court changed the wording to «commission of a collective crime», which is even funnier. Now, a meeting of the municipal deputy council and everything discussed there can be equated to a collective crime committed by a group of people. Beware, new municipal deputies!

Deputy and freedom

— In 1991 you had a small child, but you went to the White House. Weren’t you afraid? That seems to stop many people from protest activity in today’s Russia.

— Of course, I was afraid of leaving my family without a father and a husband, but I was scared to think that I would have to live in a country the image of which was offered by the putschists.

It seems to me that defending the legislature’s building in August 1991 cannot be compared to today’s protests. Back then, it was a physical defence of democracy and freedom by people who had just felt that they were citizens responsible for the fate of the country. It was a defence against an encroachment on our hopes for change.

In today’s Russia, what keeps people from protesting is the fear of harsh repression. The very right to peaceful protest which is supposedly guaranteed by our constitution as the ultimate form of feedback between the authorities and the citizens has been taken away from them by the authorities themselves. At the same time people are intimidated and persuaded that it is impossible to achieve anything with protests. But this is a lie. It is not.

—Shortly after 1993, you retired from politics for about 15 years. Why? What did you do?

—When I was still a district councilor, I went to work for the Moscow Registration Chamber (MRP), a body set up by a joint decision of the Mossovet and the Moscow government. I was head of one of the MRP’s branches. Already then, in the early 1990s, a rigid power vertical began to be built in Moscow.

After Boris Yeltsin had shot up the federal legislature, dispersed deputies of all levels, and imposed a new constitution with huge presidential powers without a public debate, it became clear that our society was moving towards authoritarianism. I simply couldn’t see myself in that system, and after October 1993 I went to work as a manager in a private business, where I remained until my arrest. At the same time, I received another [higher education] degree from the Moscow State Law Academy.

—The «Holod» piece dedicated to you says that in the 2000s, as a lawyer you defended detainees at protests, you were actually OVD-Info in a personal capacity. There didn’t seem to be much need for that back then: the fine was 500 rubles, and arrests were rare. Why were you involved in this?

—I started providing legal assistance to citizens detained at protest events when there was still no OVD-Info. It probably started with the «Strategy-31» [protest] actions.

Firstly, I defended the right of citizens to protest peacefully, to assemble and discuss issues of public life and politics. Secondly, it was clear that with the further strengthening of the established regime, repression would only intensify and it was necessary to work on ways and means of legal defence. Civil rights activists themselves also had to be trained.

I have seen that people coming out to protest are completely defenceless, although the law gives them an unconditional right (and guarantees its implementation) to receive legal aid when arrested and taken to police [stations], as well as in court.

— Why did the protests in Moscow not gather more than 100,000 even then and later? Nemtsov was killed, Navalny poisoned and imprisoned, a war started, and [yet] the same people are still in the streets.

— I think that in any country there is a small proportion of citizens who are most sensitive to injustice, who have increased empathy towards other community members, who are interested in politics, who are concerned with how democratic the state and the authorities themselves are, who are sensitive to the government’s actions, to socially significant events within the country, to violations of civil rights.

They are the first and the most sensitive element in the system of feedback between the authorities and the society. They are always the first to come out. For the rest there should be a stronger motivation.

—Why are the others silent?

— First of all, the authorities have completely suppressed any form of civil protest. Fears of reprisalsfor statements contrary to the official position on themselves and their loved ones are not unfounded. A significant proportion of our fellow citizens are zombified by state propaganda. And this is reality.

There is also a very significant category of Russians who have deliberately shut themselves off from what is happening in our society and the world, believing that everything that is happening should not concern them. There are such people here in the pre-trial detention centre. History and life show that this is only for the time being.

Representatives of this category of citizens will not take part in a protest until their personal well-being and freedom and comfort are affected. As the saying goes, until they have had enough. Not yet, apparently. But sooner or later this war will affect everyone. The mobilization announced by Putin is a good example.

— Why would a successful corporate lawyer, which you have become, need politics in the first place? Why did you return to public activity?

—It happened after the end of Putin’s second presidential term. There was a vague hope for change, for «unfreezing» real politics as one of the spheres of public activity, for moving society towards freedom and democracy. I had the strength and the need to contribute to this possible change. This is how I became involved in the Solidarnost movement in early 2009.

—When did you realise that authoritarianism was returning? When did the point of no return for modern Russia happen? Was it 1993? 1996? With the arrival of Putin? In 2011? In 2014?

— In October 1993 I had clarity about the internal political course taken by the people who had seized power by violent means.

This, I believe, was the starting point of the bifurcation, which turned out to be, as we can see today, a point of no return. This is a colossal tragedy in Russian history. But in all the years that followed, and after Putin’s first two terms, I still had hopes for political reform. His return in 2012 and the so-called Bolotnaya case put an end to my hopes.

— You became a district deputy in 1990 and in 2017. When was it easier to work and when was the work more effective?

— The question is not even to compare the simplicity and effectiveness of work for a deputy of my level. A deputy of the Council of People’s Deputies of 1990 and a municipal deputy of 2017 are totally different peoples’ representatives in status, powers, and, respectively, possibilities. And there is a crucial difference in their activities.

For instance, we initiated tough reforms in our Dzerzhinsky District Council. So, the Executive Committee, the equivalent of today’s Uprava [city government — translator’s note], was downsized and became the Council staff. Some deputies started their professional work for permanent boards. Same way I resigned from the university and joined the District Council in the position of Economic Policy Committee Vice-Chairman, later becoming its Chairman.

Perhaps, it is hard for you to imagine, but the districts of Moscow city had their own budgets independent of the city authorities, designed and approved by the deputies during heated debates; there were district banks as Gosbank [State Bank, today’s Central Bank — translator’s note] local units, district financial departments, non-housing stock owned by the People’s Deputies Council.

All questions related to a district’s life and development were in the competence of the Council’s working bodies — permanent boards. A district Council took part in the city program for district infrastructure privatization and up to 1992 registered private businesses within the district territory.

It was an interesting time. I think you would have liked it. We nearly had real local governance. But it didn’t last long, already in the second half-year 1991 during the administrative-territorial reform implemented by the Moscow City Government, our powers within the district territory began to shrink rapidly. The prefectures and small executive bodies emerged in the territories formed from 33 fractured districts. Real power was transferred to the members of the former party-administrative functionaries and Komsomol core group.

— Why did you run for municipal deputy yet again in 2017?

— To become a municipal deputy. Besides, I was a vice-chairman for Severny (Northern) district territorial election commission that time. And I had to demonstrate how to win to the generation of younger politicians, who I had organized the municipal elections for. Sike!

I used my right to stand in an election twice in my life and both times were successful. My personal count is two-nil.

— Were you planning to be reelected in 2022? Many said there was no reason to take part in a «shell game». And it seems they were right…

— Initially, I wasn’t planning it since I believed we should freshen up our team with younger members. Ilya Yashin was talking me into netting doubles with a partially renewed team. But after February 24th it became evident that these plans are doomed to fail. And, indeed, I happen to agree with you about the «shell game».

— I have also been a deputy since 2017 and it’s hard not to mention post factum that it had some sense besides citizens’ political rights protection in 2019-2020. Do you think there was any real purpose in our activities these years?

— As for me, the reason was in showing how it is possible and necessary to take down «Yedinaya Rossiya» («United Russia»). I was also interested to know and feel what the activity of a Moscow municipal deputy and a deputy council looks like nowadays in the current circumstances. To understand how the local governance system should be reformed in the future.

Finally, being a deputy with a legal background, I was in contact with the district residents (and not only them!) and got a kick out of somehow helping people to resolve their problems.

— «He wasn’t running to the barricades, more likely he was protecting those who were running to the barricades», human rights advocate Sergei Davidis said about you. Would you endorse his phrase?

— But where are these barricades? I was at the barricades in August 1991, taking part in building them and ready to repel an attack. Also, I have taken part in multiple protests in the last 12-13 years, often acting as one of the notifiers [translator’s note — of the protest to the authorities before the protest action to receive permission] or organizers.

Spontaneous protest actions, «not approved» by the authorities, definitely come with a threat of legal consequences.

Though both we and the authorities know well that the right for a peaceful protest is an essential right of the citizens guaranteed by the Russian Constitution. Therefore, while providing a participant of a protest action detained by the police with legal support, ensuring his or her judicial protection, I simultaneously protect the right of all citizens to protest. Sergei is right about this.

— How can an ordinary person fight against the war and the regime, without running to the barricades and being imprisoned? What should they do? How should they live?

— I don’t have a univocal answer to this question. I think, I don’t have the right to advise or judge anyone here. For me personally, the answer is easy. At times there are moments, when silence is not acceptable. I always speak what I consider necessary to say. And I don’t have anyone or anything to be afraid of anymore.

But I don’t get another thing: why after February 24th thousands of my fellow citizens have fled and continue fleeing despite not facing any danger yet? I suppose if we happened to be in the same place on February 24th, we could have affected a lot.

— Your attorney, Katerina Tertukhina, asked to call the War Fake Law [of the Russian Criminal Code — translator’s note] «the Gorinov law». Do you agree?

— It is a questionable sort of satisfaction having a Criminal Code article named after you. By and large, I don’t care. But if it could somehow help to eliminate it from the Criminal Code or could do any good to others involved in similar cases, I am all in favor.

The War

— You said on the night of February 22nd you dreamt «all the things that happened on February 24th and what’s happening now». On February 22nd you wrote a letter to Shoigu asking him not to do this and warned about the consequences. Why did you do this? Could it prevent the war?

— What else could I do?

In the morning of September 11th I briefly dreamt planes attacking the city of tall buildings at the bank of a gulf or a river. Several hours later the notorious terrorist attack destroying two skyscrapers happened in New York.

My dream on the night of February 22nd was truly horrible. It related to us all and had no happy ending. I don’t have a reasonable explanation for all of that. I realised that this time there was a little time to try and do something.

Additionally, we, together with public activists, submitted a notice of an anti-war march to be arranged on Tverskaya street. On February 24th I was near Pushkinskaya street where mass gathering of the citizens took place. Unfortunately, there was nothing else I could do. Maybe I would have done more, but on February 24th I was detained and jailed for 30 days. Though, I only spent 15 days in detention since Moscow City Court canceled my arrest after deeming it illegal.

— How do you think a war between Russia and Ukraine became possible at all?

— I have no rational explanation for this. The disintegration of the USSR at the end of 1991 took place peacefully, without armed conflicts. Personally, earlier I voted in a referendum for the preservation of the Soviet Union on new principles and conditions and I was glad that after the putsch, which accelerated the collapse of the USSR and thwarted its reform, everything ended so calmly.

Apparently, for all those 30 years this peaceful outcome has haunted some people. Why does it matter that as a result of revolutionary events in Ukraine power has changed? It would seem that the Russian government should have established interstate relations with the new government, developed and strengthened economic ties to the benefit of our country, by the way, using the fact that a considerable part of Ukraine’s population is Russian-speaking. Why was such an unpragmatic approach, ruinous for both countries, chosen?

After all, our state finds mutual interest with authoritarian and even frankly dictatorial regimes in other countries. Meanwhile, here we are talking about our neighbors (I’m afraid to say «brothers» now). Were there any problems with traveling to the Crimea and back before its annexation? Or did someone threaten us from the east of Ukraine? No, there is something deeply personal here, framed in an exotic ideological shell.

— What do you think about the collective responsibility that many in Eastern Europe consider necessary to apply to Russians? Are all Russians to blame for what Putin and their country are doing?

We are responsible, primarily to ourselves, for the actions of those authorities that became a threat to the security of other countries and the world’s peace. Then, of course, we bear responsibility for the pain, suffering and loss of life caused by aggression. For allowing such a regime, for tolerating it and doing nothing to end the war.

However, as a lawyer specialising in human rights, I believe that those who at least tried to create something (spoke out, protested) deserve leniency. But not those who remained silent.

— Will lustrations be necessary after the fall of the regime?

-First, we need a judicial recognition of the current regime as criminal. Lustrations can be carried out on the basis on an act of court. I confess, a few years ago I tried to develop a law on lustration, but put this matter aside, not being able to fully decide on the circle of officials to be lustrated. Here we need a collective mind and a public consensus.

— How did it happen that so many Russians supported the war?

— This is an imperialist war to acquire new territories along with their populations. For many years, by means of state propaganda, people were persuaded that the goal of the leading world powers was to seize and divide Russia, that the strength of the state and respect for it from other members of the world community depends, first of all, on its military power, and not on the level of well-being of its citizens and their social security, and not on the extent to which science and productive technologies, medicine, education and culture are developed in it.

A whole generation grew up listening to this ideology. In fact, they were simply deceived.

— Two days after your appeal hearing, Russia began a «partial» mobilization. People (even those who have not served in the army) are sent to war en masse. What will happen now?

— There will be «cargo-200» [casualties] and even more wounded and disabled people. There will be the next stage of «mogilization» [translator’s note — word play, mixture of the word mobilization with Russian word mogila, meaning grave]. All this looks like the extermination of their own people.

— What should the Russians do if they cannot leave — go to war or go to prison?

-This has already been a topic of discussion among my cell colleagues. Note that they are accused of fraud, and one, who served on a contract basis in the «militia» of Donbass before the current war, is accused of creating a laboratory of banned substances.

So, we unanimously came to the conclusion that it’s better to be imprisoned for evading [mobilization] rather than go to this incomprehensible war and return from the front disabled or not to return at all. Both conscience and hands will remain clean.

[More so since] here they feed us (though, in truth, it doesn’t taste great) and guard us, take us to courts and bring us back (though not too comfortably), let us take a shower (though [only] once a week), let us walk (an hour a day). So you can live, especially if there is support from the outside.

And if you are completely under pressure with mobilization and there seems to be nowhere to go, then here’s a piece of advice from the Matrosskaya Tishina prison inmates: go to the nearest store and steal a bottle of good cognac. At least the sentence will not be too long.

Optimism and the dog

— You, Navalny, Pivovarov and many others are in prison, Yashin is under arrest, a case has been opened against Roizman, Safronov was sentenced to 22 years. The security forces have a full carte blanche. You said in your last plea that it would take a little time for your rehabilitation and that in the future Russia you will be an ambassador to Ukraine. Why are you so optimistic?

— It is probably due to the fact that even though I have not lived long yet, but I have lived a decent life and I know that everything flows, everything changes…

Why not be future Russia’s ambassador to Ukraine first? After all, someone will have to sort this all out and build relationships. We need to think about how we will do this now. I can say one thing for now: it will be very difficult.

— When do you think «future Russia» will come and how? Is it even possible? Does the majority of Russia’s population want this other Russia?

— It is already coming every day. The political leadership of our country is accelerating this process by their own actions. The question of what the majority wants can be answered by independent opinion polls in conditions of media freedom and political debate. However, I suspect that most of the citizens do not really know what they want and how to do it. People have been misled by state propaganda about the value of democracy and freedom for them. Very soon the need for democratic reforms will become obvious to the majority.

— It seems that it is people like you who are the real patriots. Why do you love Russia? What do you love about it?

— I don’t really like talking about patriotism. This is clearly not my forte. Russia is a diverse country in terms of natural and climatic zones, in terms of the peoples who live in it. There are countless beautiful places. And everywhere in such a vast space they speak Russian. For this I love the country.

I must admit that I love not only Russia, but also our entire not so big planet Earth. Look at the pictures from space. This is a magnificent and unique place for life and peaceful development of civilization.

Moreover, humanity owns not only the Earth, but the entire solar system. It is also beautiful and versatile. All this we share. Let’s not fight, but explore and master what we, humanity, got for nothing!

— I know you’re worried that now you might never see your dog again.

— Finally, we come to the most important question of the interview! This is the second stray dog we have adopted. The first was Jack. He lived for about 18 years, but last year his life path came to an end. Chupa (Chupacabra) followed us for a long time when we walked Jack, waiting for us until we came outside.

As the cold weather began, it became obvious that she would also have to be adopted. She was almost a puppy, very thin, ugly looking. That’s why we named her so. When we put her in order, she turned out to be quite nice. Dog lovers on the street became interested in the breed, which led to much confusion. I had to come up with a breed for her — a miniature Armenian husky. I think she loves me.

Interviewer: Ilya Azar