Date of publication: 18.04.2023

Data as of 10.02.2023

Introduction

— If I go to the rally today and they catch me again, would it be considered aggravating circumstances?

— What are my options if they catch me for the third time?

— What kind of punishment can I face if they arrest me again?

— Tell me, if I participate in protests again — would it be a criminal offence?

These are the questions that arise most frequently during the waves of mass protests — when one rally is immediately followed by another. That is how it was with the anti-war protests in 2022. The police frequently try to intimidate those detained at rallies by threatening them with criminal charges in case the latter get caught again.

The option of putting a person in a colony for regularly participating in peaceful protests was introduced by mid-2014. The Criminal Code was then amended with an article on repeated violations during public events, with imprisonment for five years as the maximum punishment. New Article 212.1 (also referred to as «the Dadin article» by the last name of the first person convicted on its grounds) follows Article 212 on mass riots.

But what is actually considered a «crime», and at what point does a person end up in a «risk group»? We have thoroughly studied all cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code that we are aware of. In this Report, we explain when there is a chance of criminal prosecution and why it is harder to initiate a case than it looks. We also describe the disastrous consequences caused by Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code far beyond the matters of the freedom of assembly and tell why the article should be repealed. For details on the circumstances of each particular case, please see the Annex to the Report.

Go to the Summary of the Report

The Legislation on Rallies Made Stricter in 2014

Introducing criminal liability for peaceful rallies was another stage in making the legislation on rallies stricter. The process started at the beginning of Putin’s third presidential term, and it is not finished yet, after almost ten years.

The first significant restrictions to the freedom of assembly were introduced in 2012: a considerable increase in the amounts of fines, the introduction of community service as one of the possible punishments, the addition of a new article to the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation introducing punishment for «Organization of mass simultaneous gathering and (or) movement of citizens in public places that has entailed a public order disturbance» (Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation), the establishment of lists of places, where public events are allowed or forbidden. These changes were a response to the series of mass protests that were held against the State Duma election fraud and Vladimir Putin’s inauguration for the third presidential term, continuing from December 2011 through May 2012.

The latest changes were introduced not so long ago, in 2022, in reaction to protests against the War in Ukraine. New Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences refers to «public actions aimed at discrediting of the use of the Russian Armed Forces for protection of interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens, maintenance of international peace and security or to enable the government bodies of the Russian Federation to act in the discharge of these purposes». This article increases the punishment when the said actions are coming with «calls for unauthorized public events». One more draft law was introduced at the end of the year. It extends the list of places where rallies are forbidden, including in the proximity of the authorities and some other territories.

A significant step towards the legislation stiffening followed in 2014 when a draft law was presented in the State Duma, introducing amendments to both the Code of Administrative Offences and the Criminal Code. The authors of the law were two United Russia MPs, Alexander Sidyakin and Andrey Krasov, and A Just Russia MP Igor Zotov. Among the penalties for organizing an unauthorized event, administrative arrests were introduced, and separate penalties (including arrests again) were introduced for participation in rallies that obstructed the movement of motorized vehicles and the functioning of infrastructure (part 6.1 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences).

The most important innovation was the introduction of punishments that can be imposed with consideration to the previous offences. Article 20.2 was amended with part 8 imposing punishment for «repeated» violations of the established procedure of conducting a public event, i.e. committed within a year since the punishment for the previous violation is executed (completion of an arrest or community service, payment of a fine). It was suggested that «offenders» to this part of the article would be punished a lot more harshly: by a fine of up to 300,000 rubles (~US$8,500 at the time, ~US$3,700 as of April 2023), community service of up to 200 hours, or arrest of up to 30 days (the maximum detention period provided by the Code of Administrative Offences that previously (before these changes) had been applied to those who violated the requirements of the State of emergency or the Counterterrorism operation legal regime).

In addition to the concept of repeated violation, a notion of recurrent violation was also introduced. The latter, as suggested, would become subject to criminal punishment when committed at rallies. The new Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, as conceived by the authors, was to apply to people who had committed another «violation» while already having more than two court judgements for similar «violations» (that is, based on cases under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences) within six months. These «persistent violators» were to be punished with a fine of 600,000 to one million rubles (~US$17,000 — 28,400 at the time, ~US$7,400 — 12,400 as of April 2023), public services of up to 480 hours, corrective labour of up to two years, compulsory labour of up to five years, or detention for the same period.

Criminal Punishment for Rallies as a Response to Protests in Kyiv

One of the triggers for the legislation stiffening was the mass protests in Kyiv in late 2013 — early 2014. These protests entailed clashes that led to many casualties and the change of power in Ukraine. Russian propaganda constantly revisits the «Maidan» events, depicting them as mass riots and a series of crimes leading, on orders from the West, to overthrowing the legitimate Ukrainian government and establishing an anti-Russian regime. The name «Maidan» refers to the Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti) in Kyiv, which was the heart of the protest. By contrast, for many representatives of the Russian opposition, «Maidan'' has become an example of a successful street protest.

In February 2014, a new government was formed in Ukraine — and the new draft law was presented to the State Duma in March. One of the law’s co-authors, MP Alexander Sidyakin called their brainchild «a Maidan vaccine». During the discussions of the initiative, before it passed the first reading, on 20 May 2014, he said: «When a right for mass gatherings becomes an absolute one, the rights of a minority start to dominate over the rights of the majority. Implementing these rights might lead to events like those we saw in Ukraine. Those who participated in protests burned tires on the streets, attacked police, took stones out of paved roads and threw these stones at police. It was them who have led their country to the point where no rights granted to the Ukrainians by their constitution are preserved: the right to freedom of assembly, the right to freedom of speech, and the right to live in a safe state — all these are now nothing because a minority managed to force its will on the majority, to force its will on the state through unlawful methods. And our task as Parliament representatives is to stand against this kind of thing».

The other trigger was the protests that took place in Moscow in February and March 2014. That was the first time since 2011-2012 when a protest led to mass arrests. Two of the rallies that took place on 24 February 2014 near the Zamoskvoretsky District Court and near Manezhnaya Square (where more than 600 people in total were arrested) and became a response to the verdict in the Bolotnaya Square case are even mentioned in the explanatory note to the draft law. The protests in March were prompted by the Federation Council’s decision to authorize troops to enter Ukraine.

When presenting the draft law in the State Duma, Sidyakin stressed the need to introduce criminal liability for so-called «recidivism» when violating the legislation on rallies. The explanatory note stated: «Among 681 people detained (at the rallies on 24 February 2014 — OVD-Info) there were 49 citizens who had been previously prosecuted under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences. 3 of them had been prosecuted for more than 10 times, and 11 of them had been repeatedly subjected to administrative liability under the said article». Based on that, the MP concluded that «the law fails to fulfil its preventive function and the people who repeatedly violate the legislation on rallies, would do it again and again».

Some MPs argued against the idea of criminal prosecution for rally participants.

For example, Vladimir Fedotkin (The Communist Party of the Russian Federation, CPRF) and Valeriy Gartung (A Just Russia party) noted that those who constantly participate in rallies were not «recidivists», but people driven to despair. Gartung pointed out that the system where organizers would need to simply notify the authorities of upcoming public events had, in some regions, transformed into a regime where organizers would need to obtain permission for an event. People were being arbitrarily denied the right to organize rallies, and the courts were «effectively covering up for officials». The deputy noted that the Duma had already made the legislation on rallies stricter not so long ago (in 2012), and various ways to punish organizers of public events were already in place, so there was no need to move forward with the criminal prosecution.

Aleksandr Kravets (CPRF) considered it not fair to introduce criminal liability for those participating in mass events, while there was no such liability, for example, for those who had repeatedly crossed a road in undesignated areas. In his speech against this law, Dmitry Gudkov (A Just Russia party), also speaking out against the bill, described how police had detained peaceful citizens at a meeting with himself outside the Duma building. When arguing with the authors of the initiative, his colleague from CPRF, Nikolay Kolomeitsev, mentioned the story of a Mordovian woman who, according to her, had been fined three times for participating in a rally because of her «hostile relationship with the head of the local administration» — as Kolomeitsev noted, the law would effectively make this woman a criminal.

Sidyakin responded to these objections that the law would make the idea of «cobblestones as a weapon of the proletariat» a thing of the past and that the law was intended against those who «make holding rallies their profession, deliberately call people to the barricades, urge them to break down pavements, attack the police and break through somewhere». In his opinion, the initiative was supposed to prevent «flagrant violations of the law» (despite the fact that there was nothing about «flagrant violations» in the text of the draft law). A representative of the Committee on Constitutional Legislation and State Building, Viktor Pinsky (the United Russia party), supported his fellow party member and insisted that the initiative aimed before anything else against «professional revolutionaries» and created no difficulties for peaceful protests.

On 20 May, the majority of MPs supported the law in the first reading: 237 voted in favour and 96 against. On 1 July, the day of the second reading vote, there were no discussions: 239 out of 393 MPs supported minor changes to the text. On 4 July, in its third reading, the law was supported by 237 of 276 MPs. The law passed successfully with only some insignificant amendments. In July 2014, Article 212.1 was introduced to the Criminal Code.

How Often Is the Article Applied?

The first cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code were initiated a half year after its introduction — at the beginning of 2015. However, its use has not become widespread — at the time of publication of this Report, i.e. over eight years, we are aware of 18 criminal cases.

After the first sentence under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation was handed down — in the case against Ildar Dadin — the defence filed a complaint with the Russian Constitutional Court. On 10 February 2017, the Constitutional Court issued a ruling: the court refused to find Article 212.1 unconstitutional. However, the court emphasized that criminal cases should be initiated under this article only when a person’s actions had been intentional and had caused «a real threat» of harming one’s health or property, the environment, social order or public safety. The next criminal case was initiated only two years later, in 2019.

The use of Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code peaked in 2021, with seven new cases opened after the rallies in support of Alexei Navalny. Two more cases were initiated in 2022.

However, we cannot claim with 100% certainty that we are aware of all the cases that have ever been initiated under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. The official statements on this subject are contradictory.

An insignificant number of cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code in no way means that the rallies during the last years have seldom been a reason for initiating criminal cases. On the contrary: according to our data, since 2015, about 500 people in total have been prosecuted in Russia in criminal cases initiated, directly or indirectly, in connection with public protest actions. However, in the majority of the cases, other articles were used as a reason for conviction, and it was usually something else rather than participation in a public event that would serve as corpus delicti. In most cases, Article 318 of the Criminal Code on the use of violence against a representative of the authorities was applied. We have already noted that the punishment against public action participants under this article is, on average, more severe (and sentences longer) than against individuals who would come into confrontation with police officers under other circumstances. Article 212 of the Criminal Code on civil disorder was also applied repeatedly. In 2019 and 2021, in response to the rallies in Moscow and across all of Russia, the articles of the Criminal Code that had never been previously used against protesters were applied: on obstructing the work of election commissions (Article 141 of the Criminal Code), on abandoning children to danger (Article 125 of the Criminal Code), on violating sanitary and epidemiological standards (Article 236 of the Criminal Code), on the road blocking (Article 267 of the Criminal Code), on involving minors in dangerous activities (Article 151.2 of the Criminal Code).

Who Is the Article Being Applied Against?

Despite the law’s authors and sympathizers making statements concerning the danger of another “Maidan," Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code came into effect at the moment when “maidan” perspectives in Russia did not seem real: by the beginning of 2015, any large-scale rallies in Russia had almost come to a stop, the protest action becoming mostly local and dispersed.

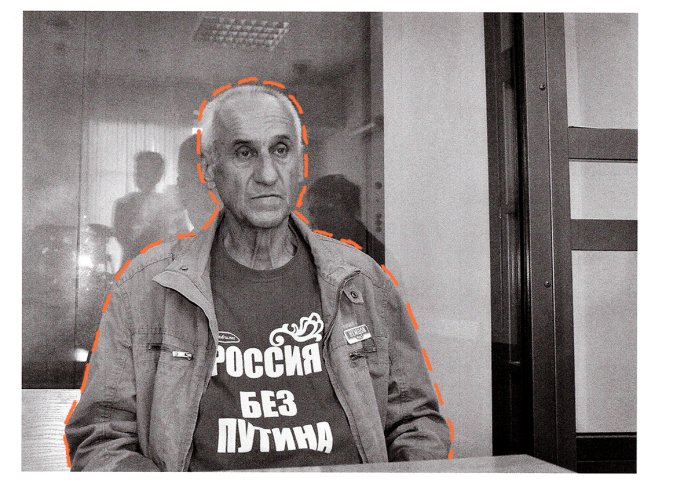

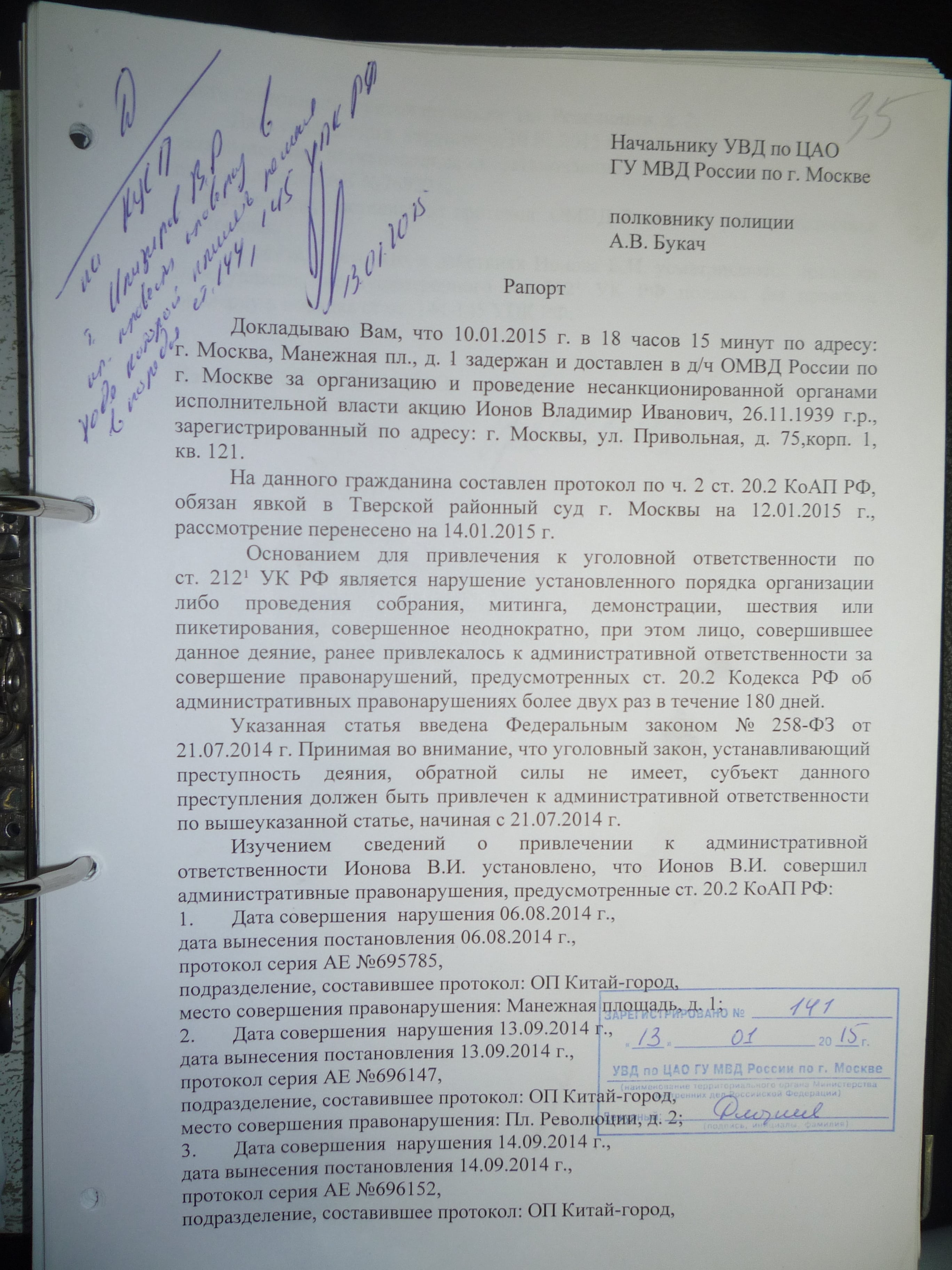

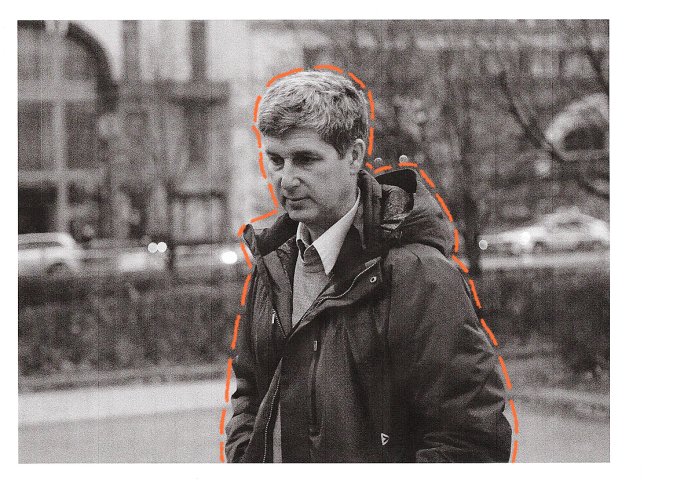

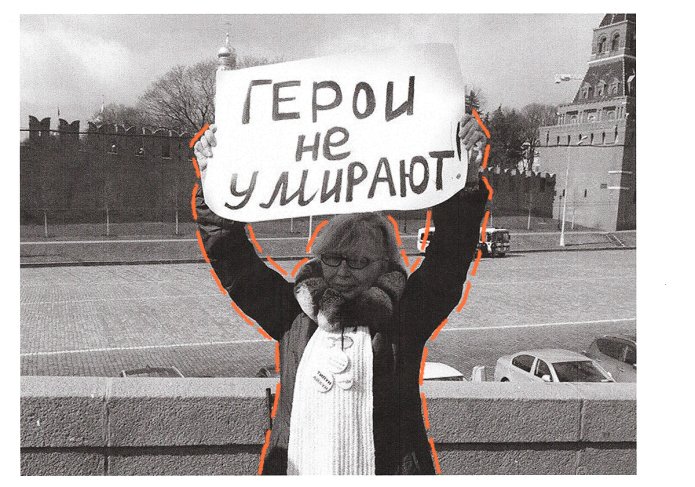

The first defendants under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code were members of a small group of Moscovites that would regularly gather in the city centre for protest actions dedicated not to the local agenda but to the federal one: Vladimir Ionov, Mark Galperin, Ildar Dadin, and Irina Kalmykova. All four cases were initiated in 2015. Till 2019, these four persons remained the only ones who this article had been applied against.

Generally, this kind of criminal cases was mostly used against street activists who would regularly participate in rallies, and every new “wave” of the article’s application would serve as a response to another rise of the protest movement.

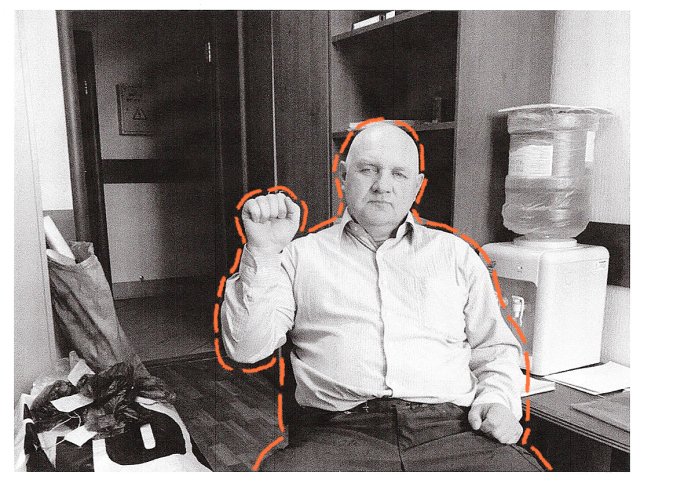

The first two cases initiated in 2019 were apparently a response to so-called “garbage protests," i.e. rallies against dumping waste from Moscow in the Moscow Region (Oblast) — Vyacheslav Yegorov's case — and in Arkhangelsk Oblast (Andrei Borovikov's case).

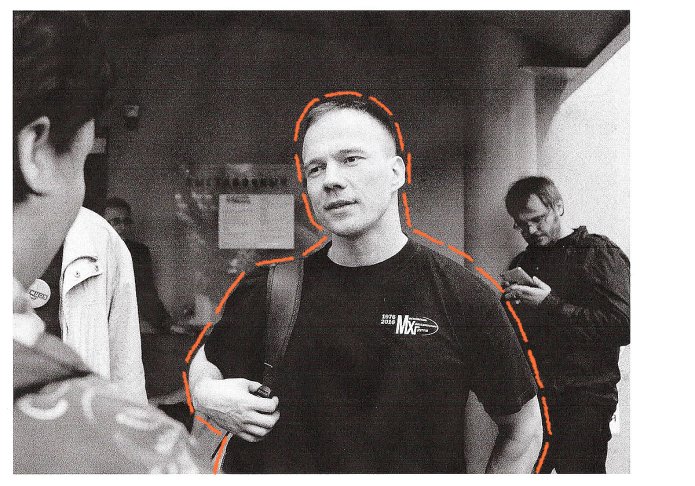

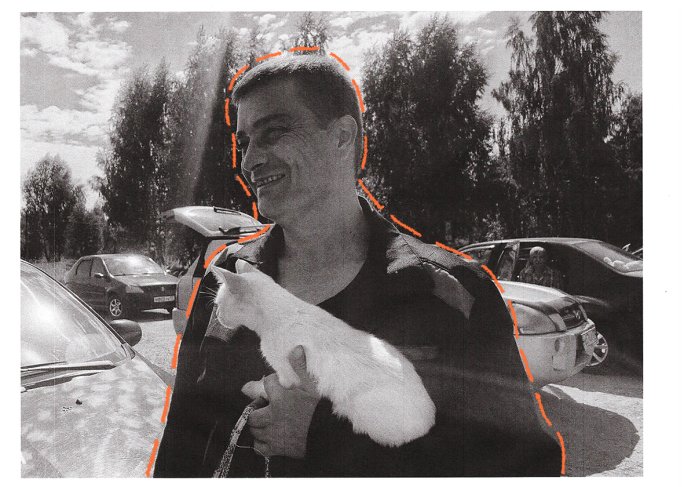

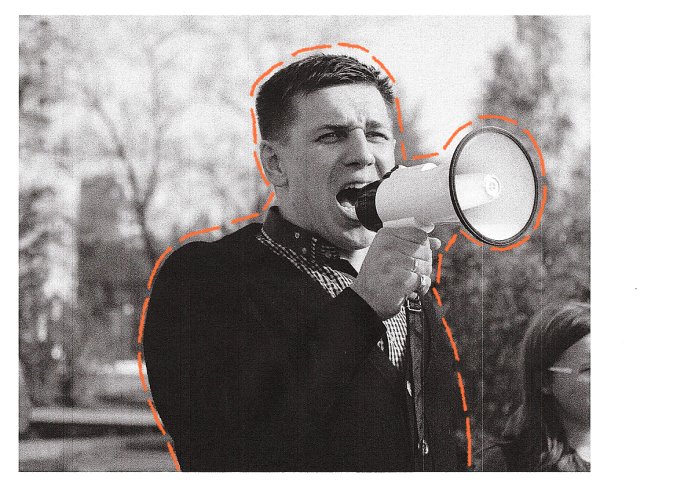

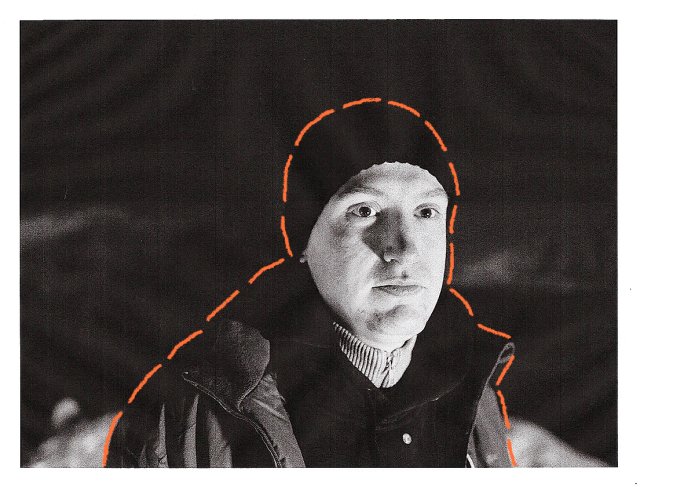

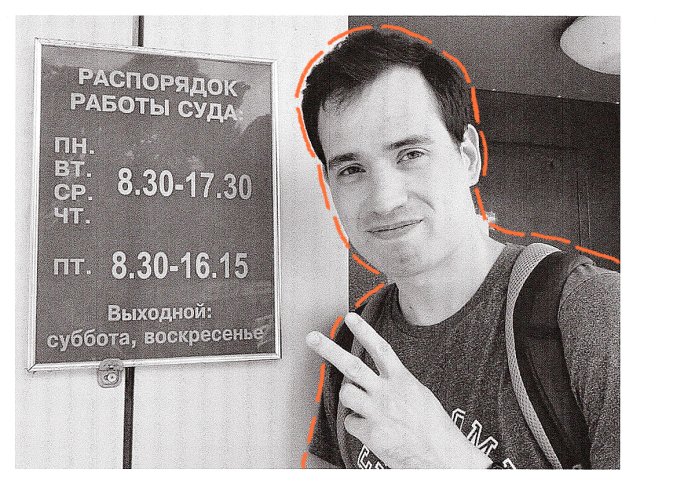

Among the defendants in the criminal cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code Konstantin Kotov deserves to be mentioned separately – he was a permanent participant in the street rallies in Moscow from late 2018 through most of 2019. Kotov would speak in support of Crimean film director Oleg Sentsov(convicted in a terrorism case), and also against the war in Donbas, in support of anarchist and mathematician Azat Miftakhov (prosecuted for breaking a window in a United Russia office), and of the journalist Ivan Golunov (accused of an attempt to sell drugs), of both defendants in the New Greatness and Network cases.

The case against Kotov was initiated in August 2019; it became part of a large wave of prosecutions responding to the protests against the non-admission of opposition candidates for elections to the Moscow City Duma. At the same time, Kotov himself could not participate in the largest rallies in support of opposition candidates, having been arrested for ten days for a post calling for protests. After his release, he tried to participate in a rally but was arrested literally 30 seconds after leaving the subway.

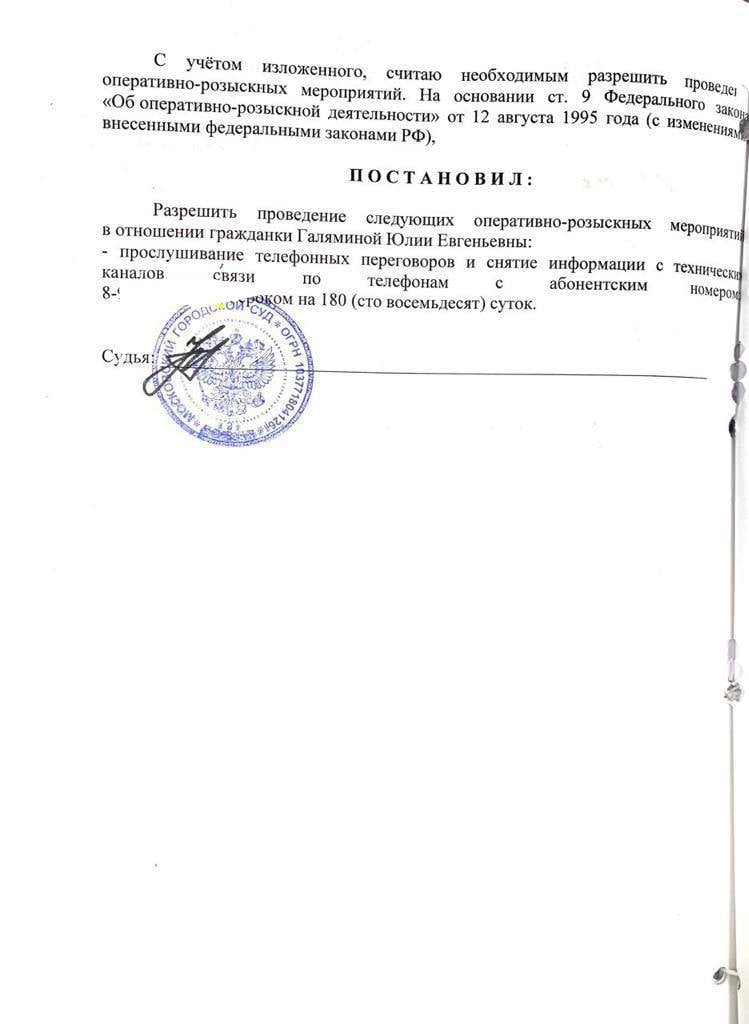

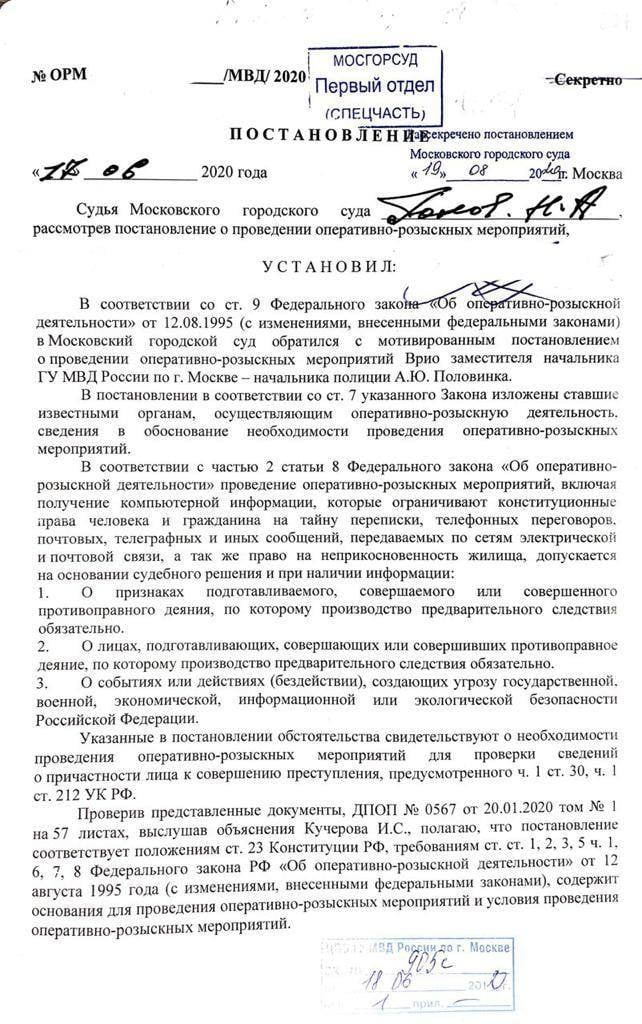

Yulia Galyamina, who had a case initiated against her in 2020, can be called one of the most prominent independent politicians in Moscow. In 2019, she actively participated in the rallies against the non-admission of opposition candidates for elections to the Moscow City Duma and in 2020, she led a campaign against the amendments to the Constitution. Moreover, Galyamina was planning to participate in the State Duma elections in 2021. However, in 2020 a law was passed banning those convicted under Article 212.1 from running for elections.

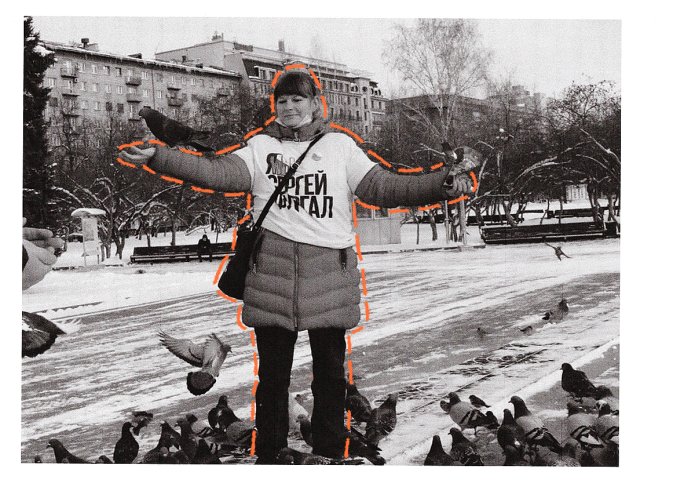

In July 2020, protests of unprecedented scale and duration broke out in support of the former governor of the Khabarovsk Region (Krai) Sergei Furgal – he was put in a pre-trial detention centre on charges of organizing murders. In response to the protests, the authorities used various pressure methods, including initiating criminal cases – one of which became the case against Alexander Prikhodko under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. Participating in rallies in support of Furgal was mentioned in at least two similar criminal cases – that of Yana Drobnokhod from Novosibirsk and that of Alexey Vorsin from Khabarovsk. In addition, many other participants in those actions were subjected to preliminary investigation under Article 212.1.

In 2021, investigative bodies initiated seven cases under this article – more than in any other year. All the defendants — the aforementioned Yana Drobnokhod and Alexey Vorsin, as well as Pavel Khokhlov from Krasnoyarsk, Victor Rau from Barnaul, Alexander Kashevarov from Chelyabinsk, Vadim Khairullin and Evgenia Fedulova from Kaliningrad — were participants of the January and April mass rallies in support of Alexei Navalny, who had been arrested upon his return to Moscow from Germany where he had been undergoing treatment after a poisoning attempt, and had been sent to a colony, with his suspended sentence in an old case having been replaced with a real one. Some of these defendants were prominent political activists in their respective regions from before the nationwide rallies in Navalny's support. Alexey Vorsin was the head of the Navalny headquarters in Khabarovsk.

The 2021 rallies in support of Alexei Navalny prompted large-scale criminal prosecutions — the so-called “palace case," — affecting over 180 people, including the aforementioned defendants in the Article 212.1 cases.

The main theme of the year 2022 was the war in Ukraine. The protest actions — not only street rallies but also public statements — resulted in criminal cases against more than 450 people. Nevertheless, the first case under Article 212.1 initiated in 2022 had nothing to do with the anti-war protests, even though the protest actions had been going on continuously for several weeks, and some of the protesters had had more than one report drawn against them under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences. A leftist activist from Moscow, Kirill Ukraintsev, was charged for another reason: in 2021, he had been prosecuted administratively for publications on protests by Delivery Club couriers and the trial over a broken window in a United Russia office. However, shortly before his detention and arrest, Ukraintsev also wrote that the couriers’ salaries had decreased due to the “special operation".

In October 2022, another case was opened under Article 212.1 – war-related this time. The reason for initiating the case against Olga Nazarenko, an activist from Ivanovo, was her anti-war actions.

Actions that Led to Criminal Prosecution

The 18 criminal cases known to us that were opened under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code are based on 85 counts of what the authorities deemed violations of the legislation on rallies.

These counts include:

- Participation in people’s gatherings, rallies, marches, mass picketing, collective performances, flash mobs, protest "walks," as well as traffic obstruction (44 counts);

- Conducting solitary pickets or participating in a series of solitary pickets (19 counts);

- Publications or series of publications on social media, which the police and/or investigation considered as organizing unauthorized events (19 counts – if several posts appear in one administrative case, we consider this as one episode). There were 14 publications in which the authors announced protest actions, and, in one case, the rally did not even take place. Two other publications — both appearing in Vyacheslav Yegorov's case — did not call for protests at all: in one post Yegorov wrote that anyone could come to the court hearing, while the other said that "people across the region cannot dream of coming out [to the streets], and even rallies are banned." Kirill Ukraintsev's case is based solely on his social media posts.

- Three more counts are related to Pavel Khokhlov’s case. Unfortunately, we were not able to find out the details of the administrative cases that led to his criminal prosecution. Based on published court rulings, it can be assumed that the violations he was charged with were linked to two collective actions and one publication.

Not a single criminal case involves burning tyres or cobblestones pulled out of the pavement, or any other atrocity that MP Sidyakin used to scare his Duma colleagues. In fact, the very wording of Article 212.1 contains nothing of the sort. The vast majority of protest actions are peaceful and are by no means always numerous, let alone solitary pickets, which certainly create no risk of mass disorder. And not a single publication called for "barricades."

However, at least four of the protest actions in connection with which cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code were initiated — 27 July 2019 in Moscow, 10 October 2020 in Khabarovsk and 23 January 2021 in Barnaul and Krasnoyarsk — were also the ones where criminal cases on violence against representatives of the authorities (Article 318 of the Criminal Code) were initiated.

However, the mere fact that a case is initiated under Article 318 of the Criminal Code is not yet evidence of the non-peaceful nature of protest actions. Based on our many years of monitoring experience, such cases are initiated either without any grounds at all or without taking into account the violence (often much more significant) on the part of the representatives of the authorities. And in Article 212.1 cases initiated because of the same protests, the events from Article 318 cases are not reflected and do not affect them in any way.

- The non-peaceful nature of the 10 October 2020 protest in Khabarovsk was not mentioned in Alexey Vorsin's case.

- The case against Alexander Prikhodko, also related to the 10 October 2020 protest action in Khabarovsk, and that of Viktor Rau, related to the 23 January 2021 rally in Barnaul, were both dropped before trial precisely because, in the opinion of the investigators, the actions of those prosecuted did not create public danger.

- The 27 July 2019 protest in Moscow, which was mentioned in Yulia Galyamina's case, was not taken into account by the court at all.

Results and Negative Consequences

Sentences

Of the 18 criminal cases under Article 212.1 that we are aware of, eight have reached conviction.

In four cases the defendants were sent to a general regime penal colony. One man, Kirill Ukraintsev, was sentenced to time in a "colony-settlement" (an open prison).

- The first sentence — three years in prison — was handed down in December 2015 to Ildar Dadin; the appeal brought the sentence down to two years and a half. The conviction was later overturned and the case was dismissed.

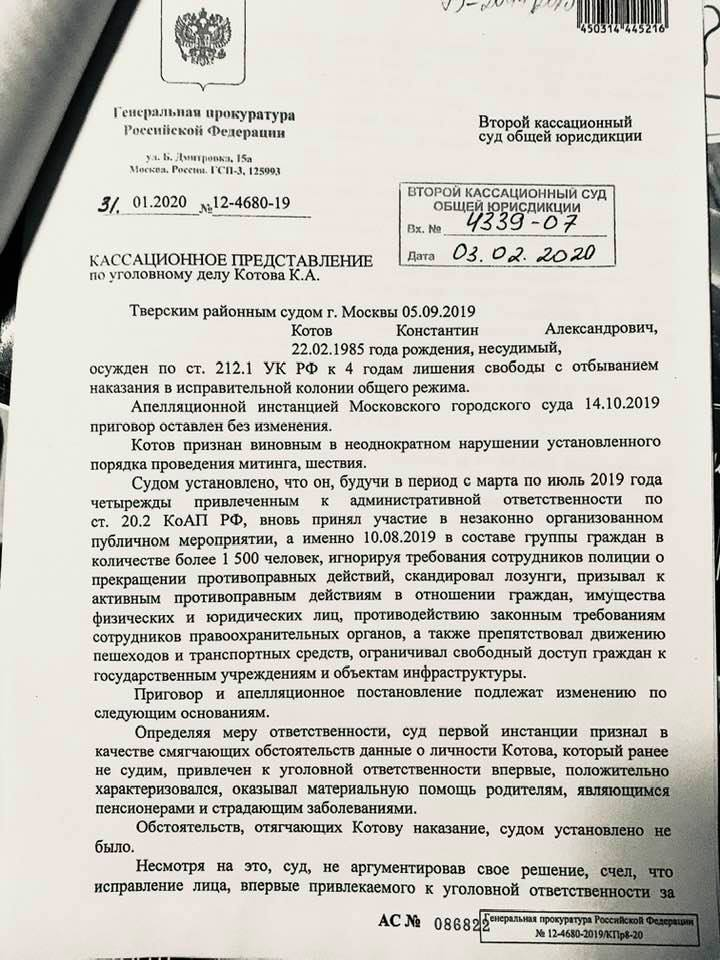

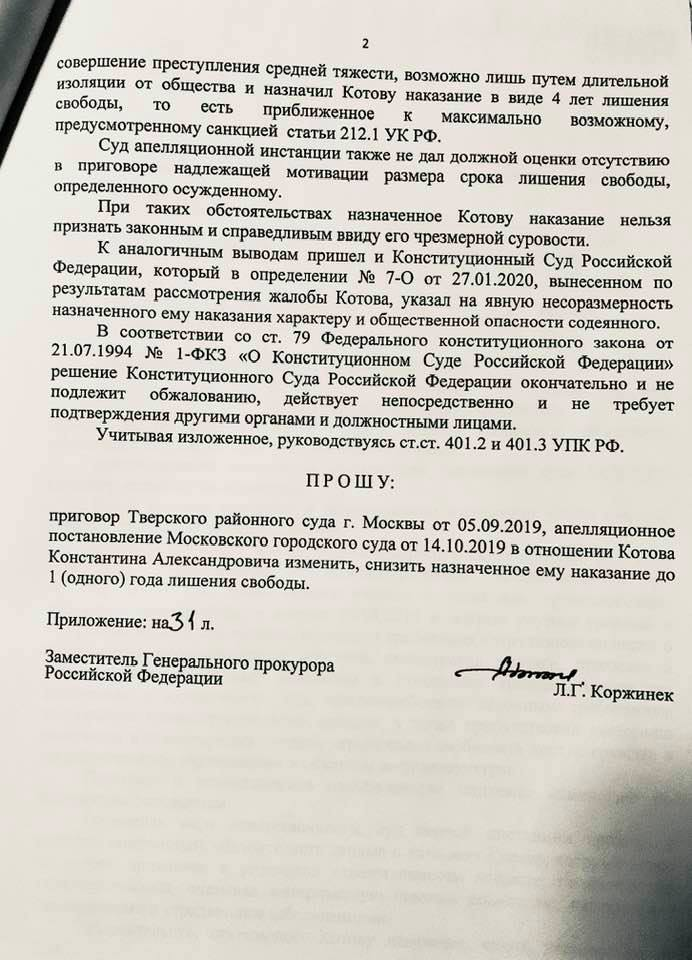

- In 2019 Konstantin Kotov was sentenced to four years in prison, which is the longest sentence handed down under Article 212.1 so far. In 2020, the Constitutional Court noted in its ruling on Kotov's case that restrictions on freedom should only be applied if the violation of the rules of a public event "involved the loss of its peaceful nature <...> or causing or actual threat of causing significant harm to individual health, property, environment, public order, public safety or other constitutionally protected values." The appeal brought Kotov's sentence down to one and a half years.

- Despite the ruling of the Constitutional Court, restrictions on freedom continue to be applied: in 2021, Vyacheslav Yegorov was sentenced to three years and three months in a penal colony and in 2022 Vadim Khairullin received a year-long prison sentence. In 2023, Kirill Ukraintsev was sentenced to one year and four months in prison, but he was released, having already served that time in custody.

Two more people received suspended sentences: Yuliya Galyamina was sentenced to two years and Alexey Vorsin was sentenced to three. One of the convicted, Andrei Borovikov, was sentenced to 400 hours of community service.

Interestingly, so far, no one has been sentenced to a fine. A Novosibirsk activist Yana Drobnokhod was required to pay a “court fine," which is not a form of punishment – her case was closed by the court (but later reopened and sent for reconsideration).

At the time of publication of this Report, Six of the cases reached the cassation stage, while two others only reached the appeal stage. In most cases, the courts of the second and third instances made no changes to the sentence, only Ildar Dadin's sentence was shortened from three to two and a half years by the appellate court (the sentence was later revoked). The decision to close Yana Drobnokhod’s case was overturned by the cassation court and the case was sent back for retrial.

The case against Konstantin Kotov was heard by the appellate and the cassation courts twice: after the appellate court made no changes to the original sentence, the Constitutional Court recommended that the case be retried, and the cassation court sent the case back to the appellate court. There, Kotov's sentence was shortened from four to one and a half years, a decision that was later confirmed by the cassation court during its reconsideration of the case.

Ildar Dadin’s guilty verdict is not reflected since his sentence was later revoked and the case was closed. Yana Drobnokhod’s case dismissal is not reflected either, since the decision to close the case was later overturned and the case was sent back for reconsideration.

Measures of restriction

The measure of restriction chosen for the duration of the investigation can serve as severe punishment in itself. At first, investigators would limit measures of restriction to personal recognizance when it came to those prosecuted under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, and house arrest was more of an exception. The first time someone was placed in custody for the duration of the investigation took place no sooner than late 2019. In total, four people were placed in custody until trial.

- Konstantin Kotov spent the entire time until the verdict came into force at a pre-trial detention centre, which amounted to a total of two months and two days (the investigation and the first instance trial were concluded speedily, most of the time he spent awaiting the appeal trial). He then spent another month and a half in detention before getting transferred to a colony.

- Pavel Khokhlov was released from custody after little more than a month.

- Yana Drobnokhod spent a month and two days in custody.

- Kirill Ukraintsev spent over 9 months in custody.

House arrest was used in the cases of four prosecuted individuals, two of whom (Ildar Dadin and Alexey Vorsin) spent the entire time pending sentencing (ten months and six months respectively) under house arrest.

- For Yana Drobnokhod, the term of house arrest amounted to 18 days.

- Vyacheslav Yegorov spent about half of a year under house arrest.

Prohibition of certain actions was chosen as a measure of restriction in two cases, one of which included severe restrictions.

- Andrei Borovikov was prohibited from communicating with the participants of the demonstration he was accused of organizing. As a result, he was formally not allowed to interact even with his own wife.

Measures of restriction may lead to professional activity being impeded.

- Vyacheslav Yegorov lost his job due to his house arrest, all the while being the only person earning money in his household.

At the same time, Olga Nazarenko was dismissed from her teaching position simply because of the fact of the criminal case initiated against her. At the time she was under recognizance not to leave.

On the other hand, no measure of restriction was chosen at all for Alexander Prikhodko, who was simply under an obligation to appear in court. Alexander Kashevarov’s personal recognizance was lifted after ten days, but was reinstated five months later (the court eventually sentenced him to prison).

Interrogations and searches

Those prosecuted under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code were subjected to interrogation and house searches.

- During the search in Kirill Ukraintsev’s apartment, his work PC, laptop and smartphones were all seized.

- During the search in Yulia Galyamina’s residence, she and her husband had their phones, computer disks and flash drives seized.

- Olga Nazarenko’s phone and savings were seized.

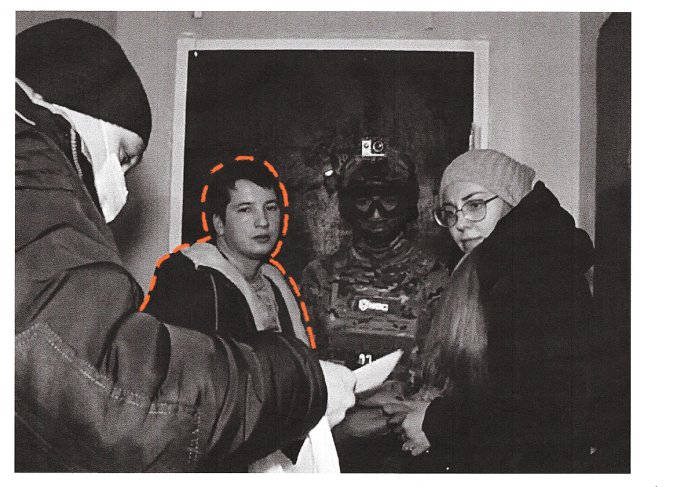

At least one of the searches was accompanied by physical violence – Alexey Vorsin reported having been struck in the face with a fist six times, to the blood, as he was being pressured to give up his phone PIN code, as well as having been beaten on his legs. He remained handcuffed for the entire four hours of the search and was not allowed to sit down or even lean against the wall. Pavel Khokhlov was also subjected to violence during his arrest.

In some cases under Article 212.1, interrogation and searches affected not only the suspects themselves but also their loved ones.

- Vyacheslav Yegorov’s case started with the searches conducted on 31 January 2019, at the homes of eight members of the “Net svalke Kolomna” (“No to the Kolomna Landfill”) initiative group. The investigator requested that FSB conduct field operational investigative activities against the members and moderators of the VKontakte groups dedicated to the landfill, “with the purpose of obtaining information regarding the bank accounts used by V.V. Yegorov and his immediate circle, as well as their possession of safety deposit boxes” and “the cash flow at the aforementioned accounts” since 1 January 2017.

- Similarly, Alexey Vorsin’s case started with searches in several people’s homes – the local FSB directorate believed them to possess “information regarding Vorsin’s illegal activities.”

- After the court hearing on the measure of restriction for Andrei Borovikov, all of the observers were issued a summons for questioning regarding his case. According to the attorney Elena Dolganova, who was working in cooperation with OVD-Info, police officers were planning to question all of the participants of the demonstration mentioned in the case.

Other negative consequences

Four persons prosecuted under Article 212.1 were forced to leave Russia because of the criminal cases initiated against them. Vladimir Ionov and Irina Kalmykova were placed on a wanted list. Victor Rau’s and Alexander Kashevarov’s cases were later dismissed.

Starting 2020, a criminal record under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, as mentioned above, disqualifies a person from running for elected government positions. Due to her guilty verdict, Yulia Galyamina lost not only her right to participate in the election but also her active mandate as the deputy of the Timiryazevsky district of Moscow.

Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code as an Intimidation Tool

OVD-Info is aware of numerous cases in which people from different regions found themselves under threat of having a case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code initiated against them, or had representatives of various government departments warn them of such a risk.

The true degree of danger may vary. Investigation of an individual’s actions for the presence of a criminal offence should be considered the form of enforcement action closest to initiating a criminal case. That procedure will be discussed further below.

There are known cases of activists receiving written warnings about the inadmissibility of breaking the law as outlined by Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code.

- The attorney defending Alina Ivanova, an activist from Moscow who had cooperated with Navalny’s organizations and regularly participated in protest actions, found such a document in her administrative case files. The administrative proceedings against Ivanova were initiated on 10 August 2019, after she was detained at the gathering in support of the opposition candidates for the Moscow City Duma. On that day, officers of the Investigative Committee came to the police department in which Ivanova was being held and conducted preventive talks with the detainees. The activist later left Russia.

- Not long before the vote on amendments to the Constitution in the summer of 2020, a participant in a demonstration for fair elections held in Moscow a year prior was visited by a police officer and handed a written warning about the inadmissibility of “committing illegal acts,” including possible criminal liability under Article 212.1.

At times judges and law enforcement officers would issue verbal warnings about the risk of criminal prosecution – despite the fact that many of the citizens that were issued such warnings had not yet reached the number of court decisions regarding administrative offences that would warrant a criminal case. Those warnings were baseless, and no consequences followed.

- In Khabarovsk, an individual was questioned and told their actions would be investigated. At the same time, they were being assured no criminal case would be initiated.

- Another activist from Khabarovsk was threatened with criminal charges by the judge who was considering his case under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences.

- In Moscow, a judge considering an administrative case on repeated violation of the law on rallies (part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences) against the activist Dmitriy Ivanov stated that the report had been drawn up incorrectly and that it was high time that a criminal case should be initiated against Ivanov under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. However, the judge later did consider the administrative case, sentencing the activist to 10 days of arrest.

- In Volgograd, an activist’s nephew was informed that his uncle would be detained again once he left the detention centre, with the purpose of conducting an investigation. The consequences are unknown to us.

These stories illustrate that law enforcers use Article 212.1 as an intimidation tool.

On top of that, liability under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code is the subject of press releases issued by authorities on the eve of mass protest actions. For example, prosecuting authorities published such announcements before rallies against the pension reform in September 2018 and before the music festival held amid protests against the construction of a landfill site in Shiyes (Arkhangelsk Oblast) in August 2019.

After the start of protests against the war in Ukraine, OVD-Info began to receive numerous testimonies about law enforcement officers threatening detainees with liability under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. Moreover, police officers also threatened detainees with part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences, claiming that charges under it may be pressed after repeat detention, even though, legally, the decision regarding the first offence must come into force for that part of the article to apply. At times the police officers’ statements seemed to imply that just two detentions were enough to entail criminal prosecution.

The following are examples of such testimonies:

- “They started <...> threatening me with criminal charges, said they will first detain me at a rally – and there will be an administrative case, and after that a criminal one right away”;

- “A criminal investigation department operative <...> said that if I hold a single-person picket again I’ll get locked up for 5 years”;

- District police officer “said that a repeat detention can be turned into a criminal case”;

- “I was detained for a single-person anti-war picket and sentenced to 10 days of arrest for disorderly conduct. They threatened me with criminal prosecution should I participate in a demonstration like this again”;

- “My coursemate, a girl, got a call – they said there had been some changes to the article, and that should we get detained again they’d press criminal charges, even though all that was not related to the article under which we had first been detained”;

- “They said that if they caught me again I’d be doing corrective labour, and the third time there’d be criminal charges”;

- “I was detained at a demonstration in January 2021 under part 5 Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences and signed a paper stating that the consequences of repeated offence were made clear to me; criminal liability was mentioned."

It seems that such statements coming from police officers may be explained not only by the complexity of wording of Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code itself, but also by the officers in question either confusing detention with court decision or deliberately intimidating citizens out of further participation in protests and demonstrations.

The numerous inquiries received by OVD-Info revealed a grave issue: the law is worded in such a way that people genuinely do not understand when the threat of criminal prosecution may arise.

Many questions and fears are caused by the vague wording of the article: it makes it impossible to parse when a person has already committed a criminal offence and when they have not yet. Drawing on written laws, the Constitutional Court judgement and the history of cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, we elaborate below on which offences may and may not form the basis for a criminal case and when the risk increases.

What Prior Violations May Lead to Criminal Charges

A criminal case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code is formed by the following formal criteria: if multiple cases of liability under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences (let us call them “prior episodes”) fall within a specific time period, the next offence (“the final episode”) becomes grounds for a criminal case.

Administrative cases under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences are most commonly initiated following a detention at a protest action, but the detention itself cannot be considered a “preliminary episode” – a drawn-up report and a court verdict are necessary. On the other hand, a report may be drawn up without detention taking place, if an individual is identified post factum. Therefore, a criminal case may technically be initiated without a single detention at a protest.

There is a possibility, even though a fairly slim one, that a single protest action may result in more than one report being drawn up on one person under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences.

- Two judgements have been issued in the case against Andrei Borovikov in connection with the protest action on 9 September 2018: the police and the court considered the rally and the subsequent demonstration as two separate events.

Different social media posts about the same protest may be treated as separate offences.

- The documents of the case against Alexey Vorsin include two posts announcing the 23 January 2021 protest action. Vorsin was fined under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences for his 21 January social media post, and his 23 January post became the final episode leading to criminal charges against him.

It is important to keep in mind that people who took part in protests are often charged with unrelated offences, such as disobedience to a lawful request of a police officer (Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences), disorderly conduct (Article 20.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences), organizing a “mass simultaneous gathering and (or) movement” (Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences), failure to comply with rules of conduct in the event of an emergency or threat thereof (Article 20.6.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences), and discrediting the activities of the armed forces (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences).

All the above-mentioned articles of the Code of Administrative Offenсes are in no way connected with Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code; therefore, administrative cases initiated under them cannot become the grounds for a corresponding criminal case.

However, it is possible to have a report drawn up against you under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences even without participating in a protest. It is not rare to see random passers-by being treated as protesters. Besides, charges can also be brought for an incorrect report on the expenditure of funds for the event or for a donation to a rally from a person designated as a “foreign agent”, as well as for a social media post announcing an unauthorized protest action.

Just having a report drawn up under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences is not enough. Only court convictions for the corresponding administrative offences can be used as grounds for initiating a criminal case. According to the data from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, in 2021, 83% of district court cases under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences ended with a conviction, and 3% of the cases were dismissed. The rest of the cases were either returned to the police or handed over to other courts, which could then hear them anew. The share of convictions can vary greatly from region to region: in Moscow, for example, it was 89% in 2021, while in St. Petersburg it was only 66%.

In any case, even having an indictment is not enough – it still has to enter into force. If a person has appealed against a court decision, it is not considered to have entered into effect until an appellate court has reviewed the appeal.

When hearing an appeal, a court can dismiss the case (then the conviction is overturned) or remand the case back to a court of first instance for a retrial. But still, in the majority of cases, the convictions end up entering into force after being appealed.

Sometimes investigators have to exclude some episodes from a criminal case or even terminate the case entirely because court rulings for administrative offences have not yet entered into force.

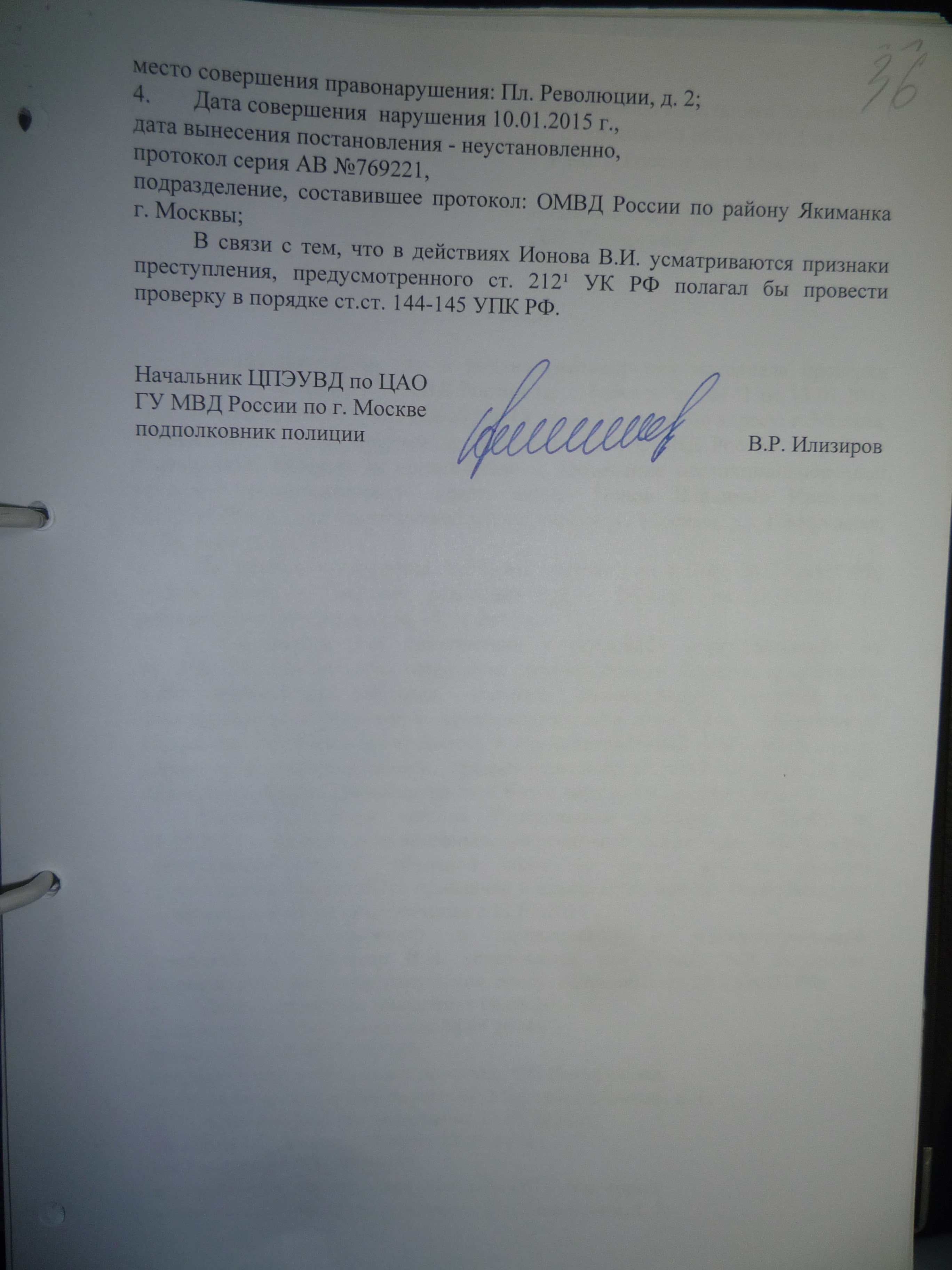

- The first cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code — against Vladimir Ionov and Mark Galperin — were initiated on 16 and 20 January 2015, respectively, even though by then court rulings for holding an unauthorized protest action on 10 January had not yet entered into force. In the case against Ionov, the authorities found a workaround by initiating a new criminal case against him half a year later and then merging it with the original one. Galperin’s case was eventually terminated.

- A similar thing happened 6 years later, in 2021, in the criminal case against Alexander Kashevarov. Half a year after the investigation into his case began, it turned out that only one out of three court decisions on administrative offences that became part of the criminal case against him had entered into effect. After this, the authorities stopped prosecuting Kashevarov.

- In the case against Alexey Vorsin, not only did one of the court rulings enter into force, but it was made by a court of first instance after the “final episode” that took place 23 on January 2021, while the ruling on the previous “episode” was made on 25 January and entered into force on 24 February. The prosecutor even tried to appeal against the ruling, but to no avail. All this did not prevent the court from eventually convicting Vorsin.

Even after a court ruling enters into force, it can still be appealed in a court of cassation. If the court of cassation overturns it, the initial court ruling can no longer be taken into account in a criminal case.

- The criminal case against Evgenia Fedulova was dismissed because a court of cassation, after having heard her appeal in connection with one of the “preliminary episodes,” remanded the respective administrative case for retrial to an appellate court that subsequently dismissed it.

How Long One Does “Preliminary Episode” Last

In order for a violation to become part of a criminal case, the violation needs to be documented and the offender punished. That can take months or even years; the process can extend depending on the duration of numerous intermediate stages.

An offence report may be drawn up not on the same day when the offence was committed, but significantly later. Unlike most articles on administrative offences, the deadline for bringing charges under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences is not three months but one year.

If a person was detained at a protest action, a report is usually drawn up right away or within several days. However, in case of a social media post or in case of bringing charges post factum, a report may be issued months later.

For instance, reports against the participants of the 2020 Khabarovsk protest actions were drawn up in bulk long later after the protests had taken place. OVD-Info reported at least 121 detentions in between protest actions. Since 2021, protesters have become detained post factum en masse, with face recognition technology being employed. Learn more about this in our report.

No more than three days are allowed to pass between the moment a report is drawn up and the moment the case reaches a court of first instance. However, if one of the possible ways of punishment is an arrest, the report must be handed over to a court “without delay.” The vast majority of parts of Article 20.2 entail an arrest. Of the most frequently used, only part 5 is "non-arrestable" – the one on violating the rules of conducting a protest action by its participants.

Article 29.6 of the Code of Administrative Offences requires courts to hear administrative cases within two months from the moment the case documents are received. However, if one of the possible ways of punishment is an arrest, a judge must hear the case “without delay.”

A court must hand-deliver its ruling or send it by mail within three days after it was made. After a person collects the ruling, they have 10 days to appeal against it. If the ruling is not appealed within this time period, it is considered to have entered into effect.

According to Article 30.5 of the Code of Administrative Offences, appeals against court rulings must be heard within two months after being received by a court. If an appellate court confirms the conviction, it is considered to have entered into force on that day.

Even in the simplest development, when a case is not remanded to previous instances, the law allows the maximum time period from the time when the offence was committed to the time when the ruling enters into effect to be one year, two months, and 13 days:

Experience shows, however, that courts do not always follow the deadlines prescribed by law. Besides, a case may be returned from a first instance court back to the police, then go to the court again, then come back from an appellate court to the first instance court, and so forth.

- As an example of an offence that was decided upon relatively quickly, we can cite one of the “preliminary episodes” in the case against Konstantin Kotov. A report for a rally at the FSB building on 13 May 2019 was drawn up on 14 May, the court arrested Kotov for five days on 15 May, and as soon as 30 May the court ruling entered into force; 17 days passed since the offence was committed.

- To the contrary, in the case against Yulia Galyamina, there were episodes related to protests of 15 and 17 July 2019, but the court rulings on them were made as late as 20 February 2020 — seven months after the offence was committed.

- Reports against Moscow municipal deputy Konstantin Yankauskas in connection with 15 and 18 July 2019 protest actions were drawn up as late as 12 December. A court reviewed them on 19 May 2020, and it was as late as 24 September (one year and two months after the offence was committed) that one of the rulings entered into force; the other one was overturned on 6 October.

- In the criminal case against Kirill Ukraintsev there was a court ruling that entered into effect one year and three months after the “offence” was committed (he published a social media post on 8 July 2020, and the ruling entered into force on 11 October 2021).

- A court ruling in the case against an LGBT activist Pavel Samburov, who was detained on Kiss Day in Moscow on 11 June 2013, entered into force only half a year later — on 18 December 2014.

A court ruling that has come into effect has a “validity period”: a person is considered “subjected to administrative punishment” from the moment it comes into force and until a year has passed from the next day after the punishment is executed (paying a fine, serving an arrest, completing compulsory work). Until a person has paid a fine, they are considered to be subjected to administrative punishment.

- In Blagoveshchensk, in December 2021, a local activist Dmitry Kravtsov was arrested by the court for 20 and 30 days following two reports of repeated violations (part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Notably, a car rally that occurred on 9 May 2020, that is, 18 months prior, appeared as a previous offence in both cases. The court fined Kravtsov on 20 May 2020; in June, the decision came into force, but according to the case files, the activist did not pay the fine until December 2021, so the old administrative case did not “expire” in a year.

- In Konstantin Yankauskas’s case, a court ruling in connection with the protest action on 14 July 2019 was issued on 27 August, coming into force on 24 October, and the “validity period” expired only over two years later, on 19 January 2022, since the fine was deducted on 18 January 2021.

Therefore, one “preliminary episode” can fit into several weeks, or it can last for over a year. The person in question has practically no influence themselves on how much time will pass from the day of the “violation” to getting rid of the “brought to administrative liability” status: only the date of the “violation," the fact of appeal and how speedily the punishment is executed (if a fine is imposed), depend on them. The rest will depend on the speed of the police and the courts’ work.

How Many “Episodes” Make Up a Criminal Case

To initiate a criminal case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, at least one “final episode” and at least three “preliminary” episodes, all fitting within a certain time frame, are required. We will go into more detail on timing in the next chapter, and here let us elaborate on the number of “episodes” needed.

- Ten defendants under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code had three decisions under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences that had come into force. The situation appears to be the same for Pavel Khokhlov, but we do not have exact information about his case.

- Six defendants (Irina Kalmykova, Konstantin Kotov, Yulia Galyamina, Yana Drobnokhod, Alexey Vorsin and Viktor Rau) had four rulings that had entered into force.

Yulia Galyamina had six decrees that had entered into force.

The “final episode” of a criminal case is an action that the police consider an offence falling under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences. At the same time, it is important that the “final episode” has not had an indictment within the framework of the Code of Administrative Offences – if the court has already assessed it in accordance with the Code of Administrative Offences, a criminal case cannot be initiated.

- In the first cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code (in relation to Vladimir Ionov and Mark Galperin), decisions on administrative cases that later became “final episodes” had been made before criminal cases were opened. Both of the defendants later had their “final episodes” changed. But in Galperin’s new “final episode," too, a ruling had been issued for an administrative case, so the criminal case fell apart.

- The Constitutional Court, in a 2017 judgement on Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, stated that violation of the established procedure of holding public events becomes a reason for initiating a criminal case “only on the condition that for the incriminated act, the person has not been subjected to administrative punishment for an administrative offence provided for by this article (Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences — OVD-Info)."

In some cases, there is more than one “final episode.”

- In the case against Yulia Galyamina, the “final episodes” were several publications on social media in July 2020 with a call to participate in the 15 July rally.

- In the case against Yana Drobnokhod, the “final episodes” were the protests on 23 January 2021 in support of Sergei Furgal and Alexei Navalny (the investigation considered them as two violations following immediately one after the other) and on 30 January 2021 in support of Furgal. Therefore, there were formally three “final episodes” in the Drobnokhod case – the investigation deemed her to have committed a violation twice on 23 January: from 11:40 to 14:20 she participated in a picket in support of Furgal, and from 14:20 to 15:00 – in a rally in support of Navalny.

Thus, police officers’ statements that, after being arrested, a subsequent arrest automatically leads to a criminal case, are untrue. Article 212.1 takes into account not arrests, but court decisions, and furthermore, there must clearly be more than two of them.

Either police officers deliberately misinform the detainees for the purpose of intimidation, or they actually do not understand how Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code works. Perhaps law enforcement officers confuse this article with other articles of the Criminal Code that depend on the Code of Administrative Offences too. For instance, in March 2022, Article 20.3.3 on discrediting the Armed Forces was included in the Code of Administrative Offences, and immediately began to be applied against anti-war protesters. And Article 280.3, with similar wording, was introduced into the Criminal Code; the first part of that article suggests that a case can be initiated if there is only one court decision under Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences that has entered into force during the year.

How Much Time Has to Pass Between "Episodes"

A criminal case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code consists not of any “episodes," but only of those falling within a certain period of time. Neither the article itself nor the Constitutional Court’s further explanations provide an unambiguous understanding of how these terms should be calculated. This chapter will elaborate the main points of contention, possible interpretations and compare all those with real practice.

When creating the new article, legislators completed it with a note explaining what should be considered a “repeated violation of the established procedure of organizing or holding a rally”: “A violation of the established procedure <...> repeatedly committed by a person, is a violation <...> if the said person has been previously brought to administrative liability for committing administrative offences under Article 20.2 <...> more than twice within one hundred and eighty days.”

I.e., the “final episode” becomes the basis for initiating a criminal case if by that moment a person has had at least three “preliminary episodes” in 180 days.

Moreover, the 180 days are calculated not from the date of the “violation” in the first “preliminary episode," but from the moment of “bringing to liability” in an administrative case.

Therefore, if a person committed three offences within six months, but for one of them a ruling was issued, for example, in January, for the second – in May, and for the third – in November, then the three of them do not add up to a criminal case. If a report was drawn up for a person four times during one week under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences, the fourth time will not be able to become "final" – after all, the rulings will not yet have come into force.

And vice versa – if the offences themselves occur in January, May and November, and the rulings on them are issued within six months, then the person has the required number of “preliminary episodes."

However, it remains unclear what dates should be included in the stipulated 180 days – the date of the decisions of the courts of the first instance or the date when the decisions entered into force. Judging by the text of Article 4.5 of the Code of Administrative Offences, the moment of bringing to liability should be understood as the date a court of first instance issues a ruling. But in practice, in some cases, the countdown starts from the date of the ruling, and in others – from the date the rulings come into force.

- Judging by the order regarding the initiation of a criminal case against Kirill Ukraintsev, the investigation was taking into account precisely the dates when the decisions came into force. It is these dates that fall within the required interval of 180 days, whereas the dates the rulings were issued by the courts of first instance do not. The judgements were issued on 2 March 2021, 27 May 2021, and 14 September 2021, so more than six months passed between the first and third of them. The rulings came into force on 21 July 2021, 22 September 2021 and 11 October 2021. In other criminal cases known to us, the dates the courts of the first instance issued the rulings fit into the required interval.

- Interestingly, the court decisions in Ukraintsev’s administrative cases entered into force in reverse chronological order with respect to the offences. The order to initiate criminal proceedings indicated that Ukraintsev first published a post on 30 October 2020 (the ruling entered into force on 21 July 2021), then, “continuing his illegal actions,” published a post on 12 October 2020 (the ruling entered into force on 22 September) and finally, “despite being brought to administrative liability yet again <...>, without drawing proper conclusions,” published a post on 8 July 2020 (the ruling entered into force on 11 October 2021).

- There were six “preliminary episodes” in Yulia Galyamina's indictment, but the court decided to not take into account two of them, as the dates when the respective rulings entered into force did not fit within the six-months period.

Moreover, it remains unclear whether the “final episode” should also fall into the 180-day interval.

Assuming that the “final episode” is not included in the 180 days, the case may include “violations” that are further in time from the“final” one.

- In the case against Yulia Galyamina, the rulings on “preliminary episodes” were issued in July, August, and December 2019. The “final episode” happened in July 2020, that is, a year after the first “preliminary” ruling.

In this case, it is necessary to take into account the above-mentioned “validity period” of a court ruling in an administrative case: no more than a year should pass between the moment the punishment for the earliest “preliminary episode” is executed and the final “violation.”

In most criminal cases, the “final episode” fits into the same six-month period as the “preliminary” ones.

- For example, in Vadim Khairullin’s case, the rulings were issued in January and February, entered into force in February and March 2021, and the “final episode” took place in April.

- In Yana Drobnokhod’s case, the rulings on “preliminary episodes” were issued in October and November 2020, and the “final episodes” (there were more than one of them) took place in January 2021.

Sometimes the “final episode” does not fit into the same six-month period with all the “preliminary” episodes, if calculated based on the dates when the courts of the first instance issued the rulings – but fits in that period if calculated by the dates the rulings came into force.

- In Vyacheslav Yegorov’s case, the “final episode” happened on 13 December 2019. The first "preliminary" ruling of the court of the first instance falls on 11 May, and of the appellate court – on 26 June.

In Andrei Borovikov’s case, the investigative officers intentionally argued that the last “violation” fits within the six-month period after the first indictment came into effect. In his case, the indictment on the first “preliminary episode” came into effect in September, while the “final episode” happened in April 2019, that is, more than six months later. But the investigation insisted that Borovikov's activities in organizing the event on 7 April began on 22 March, i.e. 178 days after the ruling on the first event that would become part of the criminal case came into effect.

According to the Constitutional Court judgement of 2017, it can be assumed that the “final episode” should still be included in the 180-day period. Therefore, decisions on “preliminary episodes” must be made just prior to the last “violation.

Who and How Initiates Cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code

When can a case be initiated

A criminal case can be initiated within six years after the “final episode.” This is the validity period for crimes of “medium gravity,” which includes “repeated violation of the established procedure of holding a rally.”

In cases under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code known to us, the period within which a case was initiated ranged from one day to six months.

- In Yana Drobnokhod’s case, the “final episode” was her being detained at a gathering in support of Sergei Furgal, the former governor of the Khabarovsk Krai, on 30 January 2021. The fact that a criminal case was initiated became known literally on the same day.

- The maximum period between the “final episode” and the beginning of criminal prosecution is observed in the case against Kirill Ukraintsev. The post he published on 12 October 2021 became the reason for the case being initiated on 25 April, 2022.

Who Can Initiate a Case

Both the Investigative Committee and the MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs) investigators can initiate a case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. Most (12) cases known to us, including the very first ones, were opened by the Investigative Committee. The MVD initiated six cases (against Andrei Borovikov, Pavel Khokhlov, Yana Drobnokhod, Alexander Kashevarov, Viktor Rau, and Olga Nazarenko).

There are known cases of case files being transferred from the MVD to the Investigative Committee.

- After the number of Vyacheslav Yegorov’s “preliminary episodes” amounted to three, the Kolomna Directorate of MVD (Moscow Oblast) sent the preliminary investigation files for the initiation of a criminal case to the Main Investigative Directorate of the Investigative Committee in Moscow Oblast. However, the Main Investigative Directorate returned the files. It was explained that there was already a court order under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences that had come into force for all three offences, but there was no “final episode” necessary to initiate a case. Later, when the “final episode” did appear, the police drew up an administrative offence report under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences and handed it over to the Investigative Committee, which opened a criminal case.

- In Khabarovsk Krai, the MVD sent information to the Investigative Committee to conduct a preliminary investigation against several local activists. The IC returned the files, stating that the MVD could initiate cases under Article 212.1 itself. Later, it was the Investigative Committee that initiated the case against one of them, Alexey Vorsin. The other activists did not have proceedings initiated against them.

What Kind of Information is Required to Initiate a Case, and Who Has Access to the Data?

For an investigative officer, the main difficulty of initiating a case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code is that the “final episode” — the action that triggers the mechanism of criminal prosecution — does not differ from an administrative offence. They need to pay attention to a specific person and assess the presence of:

- a sufficient number of “preliminary episodes”;

- a “final episode”;

- “public danger" in the actions of a potential criminal. In 2017, the Constitutional Court deemed it to be necessary.

To understand that the “preliminary episodes” are not yet outdated, the respective rulings have come into force for all of them and are fitting within the required time, it is necessary to have a thoroughly documented judicial history of each administrative case and information about the date of execution of the punishment. At the same time, it must be taken into account that a court ruling should not yet be passed for the “final episode.”

The files from Ildar Dadin’s case, initiated back in 2015, show that at that time the investigators did not have all the necessary information. It contains an excerpt "from the Database on bringing Dadin I.I. to administrative liability." In addition, the case provides information about two and a half dozen detentions from March 2012 to September 2014. I.e., the violations with an expired “validity period” were included too. The cases mentioned are not only those initiated under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences but also those under Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (disobedience to a lawful request of a police officer). Both the dates of detention at protest actions and the dates of court rulings were included in these cases of “bringing to administrative liability" in the extract from the “Database,” and they were mixed up. The information about whether the rulings had come into force did not make it to the extract.

At the end of 2016, the police either did not understand the analysis of which data was necessary to initiate a case or did not have such data. This is demonstrated by the attempt to open proceedings against Igor Klochkov, an activist from Moscow.

- In December 2016, the Centre for Combating Extremism demanded from the Tverskoy District Court of Moscow the files of administrative cases against Klochkov to initiate a case under Article 212.1. But the judge refused because the court decisions had not yet come into force.

But even in 2021, at least one criminal case had “preliminary episodes” with rulings that had not come into force. We elaborate on this case in the chapter “What Prior Violations May Lead to Criminal Charges”.

What information do law enforcement officers have?

Is all the necessary information regarding prior administrative cases available to police officers when they decide whether to initiate an administrative offence case under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences?

When a court issues a ruling, its copy must be sent to the police officer who drew up the report. A similar procedure is stipulated when a ruling is made in the event of an appeal. Who will be notified of the execution of punishment depends on the type of sanction: the court is notified of the arrest, and the bailiffs service is notified of community service. Banks submit data on payment of fines to the “State Information System on State and Municipal Payments."

The administration of the place where an administrative arrest is served is obliged to notify the judge who issued the administrative arrest order about the beginning, place, and end of serving the administrative arrest by persons subjected to administrative arrest. The administration must also provide information on the existence of the grounds specified in part 3 of Article 17 of this Federal Law for suspending or terminating the execution of administrative arrest orders.

A copy of the decision made by the judge on the complaint against the decision in the case of an administrative offence considered by the judge is sent within three days after being issued to the official who drew up the report on the administrative offence.

It follows from the laws that information about persons who have committed an administrative offence is stored in police “data banks." The Investigative Committee is one of the entities that rely on this data in its work: an investigative officer considering a case and wishing to obtain information from the MVD databases submits either a request to the department or an instruction to MVD operatives to provide information as part of operational investigative activities.

Recently, an impressive number of various electronic databases containing data on Russian citizens have appeared in the arsenal of law enforcement officers. We will mention only those of them that we often find in court rulings on cases regarding rallies.

Information about court rulings already issued to a person under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences is contained in the Integrated Data bank of the MVD of the federal (IBD-F) or regional level (IBD-R[egional]) in the “Administrative Practice" section. We do not know much about the structure of these databases. Some light on this, although only for one region, is shed by the published order of the Main Directorate of the MVD of St. Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast, which gives instructions on how to enter data into the “Administrative Practice" database. The order was issued in 2011 and is still in effect. According to this document, it is assumed that the information that police officers should enter into the database is related to outcomes of court cases and the payments of fines (the document does not mention arrest or community service), as well as check with the database when initiating an administrative offence case.

IBD references can be found among evidence in court rulings. But the examples that we have been able to find only mention information on previous cases of bringing to liability and on penalties imposed, but not on rulings coming into effect.

- A ruling issued by the Zyuzino District Court of Moscow, dated 18 April 2022, on a case on repeated violation of established procedure of holding public events (p. 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code for Administrative Offences) claims that “The facts of the administrative violation being committed by Chidaran S.A. are confirmed <…> by the information from IBD-R and by a reference to an individual, according to which, Chidaran S.A. was brought to administrative liability under part 5 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences on 24 October 2019 and 31 July 2020. She has a fine of 10,000 rubles (~US$125 both at the time and as of April 2023) imposed on her, the information on payment of the fine is not available.”

- A ruling issued by the Kolpashevsky City Court of Tomsk Oblast on 11 October 2022 on the case on disobedience to police officers (Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) stated that “according to an IBD reference on administrative offences, In 2021, Kireev O.V. was repeatedly brought to administrative liability under Chapter 19 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation. The administrative penalties imposed have not been executed to date."

Police are also using the “AS Russian Passport” database. One of the administrative cases that we have access to features a record extract from this system. Judging by the document, the database contains information not only on passports, but also on administrative offences, including offence dates, report compilation dates, and dates of bringing the people in question to liability – but no information on the date when rulings come into force.

Nevertheless, during Alexey Vorsin's court proceedings, at the request of the prosecutor, the Khabarovsk Internal Affairs Bureau sent a spreadsheet containing information about those prosecuted for the 23 January 2021 protest action, with a column titled "Date of entry into legal force." Where exactly this information was drawn from is unknown.

It seems that the police are not always able to check if a person has enough rulings to start a case under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code. According to lawyers cooperating with OVD-Info, a police officer has to make a call to the Information Centre of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and give their password to obtain information on prior cases.

- On Saturday 5 November 2022, Ilya Povyshev was detained by the police in Moscow, wearing a mask with an anti-war inscription. At the police station he was charged with "repeated" violation at a protest action – under part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences. However, the police officers claimed that they had no way of confirming that the prior violation under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences had come into force – they would not be able to do this until Monday. They refused to provide a copy of the report and left the detainee at the station until Monday. According to the law, such a long detention is possible if the report is drawn up under part 8, but if the previous "violation" had not been confirmed and the report was drawn up under part 5, the detention should not have exceeded three hours.

Judging from this case, at least over the weekend the police may not have access to full information on previous administrative offences, their trial and the execution of the penalty. This means that a person can only be suspected of an offence under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code after a manual check and not always immediately.

Despite the problems described above with access to at least part of the information, it is clear that the level of technical equipment of the police will continue to grow.

In recent years, the Ministry of the Interior has been working to improve its databases. The authors of the "Net Freedoms" 2022 report "Political profiling technologies" describe the attempts by the MVD to create a system that would integrate "disparate regional and departmental data banks and police databases." "The system, dubbed 'IBD-F 2.0', was intended to replace the obsolete IBD-F[federal] scheme, created at the end of the last century, and IBD-R[egional], which brings together autonomous police databases. The new generation programme was to provide centralised automated maintenance of all police records (investigative, operational, forensic and other) and their interaction with databases of federal and regional authorities, municipalities, state and municipal institutions," the report says.

The first attempts to create a unified base failed due to disagreements between the MVD and its contractor. But it is possible that the introduction of a new, improved system combining the existing bases could result in less selective prosecutions for "repeated offences."

How information is collected before a case is initiated

According to Article 140 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, a message about a crime may become grounds for an investigation. The message, in this case, can be someone’s statement, a confession of a crime, a report from a law enforcement officer, or a prosecutor’s order to send respective files to a preliminary investigation body.

Article 143 of the Code of Criminal Procedure states that a report is written if the information regarding a crime (committed or prepared to be committed) is received from sources other than a statement, a confession, or a prosecutor’s order. A court ruling, a publication in the media, or a direct observation of a crime can serve as reasons for a report.

In the cases known to us under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, the report is the starting point, as the relevant information is initially at the disposal of law enforcement agencies and courts.

After the message about a crime is received, an enquiry officer, an enquiry body, an investigative officer or a head of an investigating body must conduct a preliminary investigation to answer the question if the event contains in fact elements of a crime.