This is a story of a human rights activist from a secret nuclear town. Witness her resilience and transformation from selling socks on the street to confronting the FSB and the Russian Atomic Corporation. For 15 years, Nadezhda Kutepova and her organization, Planet of Hope, tirelessly championed the rights of those impacted by radioactive contamination in a secret Siberian town where weapon-grade plutonium is produced. But when the Kremlin labelled the organisation a «foreign agent», their vital work was abruptly halted.

On July 2, 2015, Nadezhda Kutepova was making dinner when she heard a news story about spies on TV. On the screen, infamous propagandist anchorwoman Olga Skabeyeva was approaching the entrance of Nadezhda’s building. Skabeyeva then climbed the stairs and pointed to Nadezhda’s apartment: «Espionageagainst our state are being conducted from here». The activist explained it was easy to recognize her door because of the «funny old doorbell hanging on the wire»; one could certainly say «the spy» wasn’t very wealthy. A few days later, she fled Russia with her three children never to return.

Nadezhda lived in Ozersk, a tightly guarded, closed town in the Chelyabinsk region. Closed towns are a Soviet relic — they are built around secretive defence factories and research labs. Entrance is forbidden to outsiders, the checkpoints are guarded by security services and one can only come in and out with special documents. Ozersk is home to the Mayak Production Association, tasked with processing and storing radioactive materials from nuclear power plants, submarines, and icebreakers, while also producing weapons-grade plutonium. Established in the late 1940s for the production of plutonium for the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb, Ozersk remains shrouded in secrecy.

According to official statistics, cancer ranks among the top three leading causes of death in Ozersk.

«Don’t sit in the snow, it’s dirty»

On September 29, 1957, a catastrophic explosion rocked the Mayak Chemical Plant, situated in the town then known as Chelyabinsk-40. The resulting radioactive cloud covered an expanse of 20 thousand square kilometres. Within a month, 23 villages in the district were evacuated, displacing roughly 12, 000 residents whose properties and livestock were burned. The broad Soviet population remained unaware of the incident until 1989, when state archives were unveiled during Perestroika. Today, the Mayak explosion ranks as the third of history’s worst nuclear disaster, following Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Among the emergency workers sent to clean up and restore the irradiated plant was Lev, who would later become Nadezhda’s father. At just 18 years old, he was drafted to serve in Chelyabinsk-40. After his service in the cleanup efforts, he decided to remain in the secret town due to its higher standard of living compared to his Siberian hometown of Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg). Lev studied engineering and secured a job at a nuclear waste recycling plant. He got married, and later his first daughter, Natalia, was born. Nadezhda shared that her older sister, whom she never met, suffered from a brain disease linked to the radiation exposure her father experienced during the cleanup. She passed away at 20, after spending her entire life in mental institutions.

Later, Lev met Larisa, Nadezhda’s mother. They got married in 1971. Lev died of cancer in 1985, when his second daughter was just 13 years old. Nadezhda’s grandmother on the mother’s side, Nadezhda Ivanovna, also passed away from cancer. She was among the pioneering creators of the first Soviet atomic bomb. Nadezhda as described her as «crafting plutonium with her own hands».

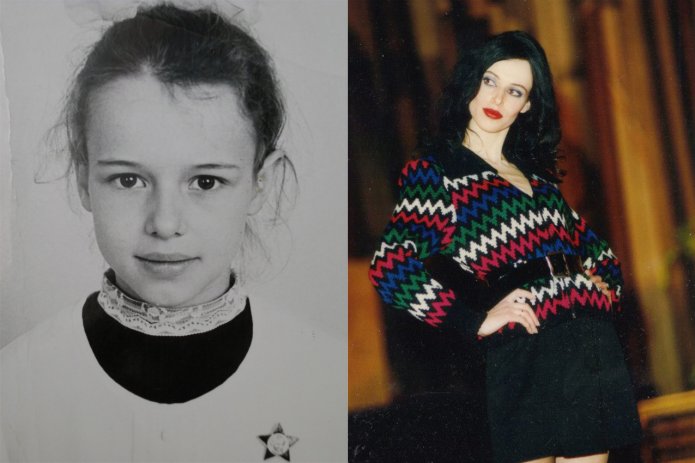

In 1990, Nadezhda graduated from nursing school and started her career as an ER nurse. Later, she pursued further education at the Sociology Department of Ural State University. At the same time, she engaged in trading at the local Ozersk market. Nadezhda vividly recalls the time from 1993 to 1999, freezing winters and scorching summers while selling socks at the market to finance her education. «This is an important aspect of my life journey», she emphasizes, «and I’ve never shied away from it. Working at the market allowed me to truly connect with the people of Ozersk».

In 1998, upon learning that the Yekaterinburg fashion agency Alexandria was seeking recruits for a modelling school, Nadezhda enrolled in classes while juggling her work at the local market. Eventually, she dedicated six months to the catwalk.

In 1999, following her university graduation, Nadezhda stumbled upon a seminar hosted by the Chelyabinsk-based Movement for Nuclear Safety. Even though a decade passed since the story of the Mayak disaster was revealed to the world, Ozersk remained resistant to external scrutiny. State propaganda vilified environmental groups, accusing them of corruption and espionage. «We were constantly reminded to trust no one», Nadezhda reflects.

In 2006, under the directive of Rosatom (the Russian Atomic Corporation), a survey was conducted among a thousand residents of Ozersk. The findings revealed that approximately 70% of respondents placed their trust in Mayak regarding environmental safety matters. Interestingly, two-thirds of those surveyed attributed responsibility for radioactive discharges into the Techa River near Ozersk from 1949 to 1952, as well as for the 1957 disaster, not to the enterprise itself, but to the authorities. Furthermore, over half of the respondents expressed health concerns, attributing their ailments not to radiation but to stress and substandard medical care.

Local resident Nastya (name changed — OVD-Info) reveals that discussing cancer and its connection with Mayak was a taboo—it was a topic «swept under the rug». Nastya’s grandfather, much like Nadezhda’s father, was also a liquidator of the 1957 accident. As a young conscript, he was sent to a new city. «In the 1980s, he fell ill very suddenly. He died within months», Nastya shares. Despite treatment in a specialized local hospital, her father’s condition worsened, leading to his eventual passing at home. Official records cited heart failure as the cause of death — a scenario mirrored in many families, according to Nastya.

People in the neighbouring cities had their own stereotypes about the residents of Ozersk. Nastya gives an example of a typical dialogue in Ekaterinburg in the early 2000s:

— Where are you from?

— From Ozersk.

— Do you glow in the dark?

— Of course. They haven’t even cut off my tail yet.

Only at the age of 16, after a trip to Siberian town Nizhny Tagil, Nastya realised that other cities, unlike Ozersk, were open. In order to enter them, one did not have to pass the «border» with checkpoints, FSB officers and a barbwire: «All of this was instilled in us as part of our worldview. „The city doesn’t exist; we are [supposed to tell outsiders that we are from] Chelyabinsk [a major city nearby]. We don’t ask questions“».

Like other residents of Ozersk, Nadezhda Kutepova believed in the validity of such isolation and compliance. She says that she «woke up» when listening to a report about her hometown by ecologist Vladimir Usachev, also from Ozersk, at a seminar. At that time he headed a local environmental protection committee. Kutepova compared the expert data with her own observations — «and it hit me at once». «For example, my mother told me when I was a child, that I can’t sit in the snow, it’s dirty. But it’s white, how could it be dirty? She meant that it was radioactive, but she couldn’t pronounce [the word]. Or, for example, I really liked to take a broom from the street-cleaner and sweep the dust. A neighbour would run up shouting: „What are you doing?!“ In our town, no one was allowed to sweep, especially children [as this results in radioactive dust rising into the air]. Or, for example, [in Ozersk] the streets were washed more often [than in other cities]».

«A person from the future»

Inspired by the seminar, Nadezhda Kutepova registered her own public organisation on 21 April 2000. Planet of Hope started with computer courses for pregnant women.

It was then that Nastya, then 19–year-old student, met Nadezhda. She was struck by the appearance of the young social activist. Tall, slender, wearing makeup, looking stylish, and with a huge belly (when organising the courses, Nadezhda was herself in the late weeks of pregnancy). And with a very strange haircut by the standards of Ozersk: «The hair is 3-4 centimetres long and bleached. At that time I thought that only the people battling severe cancer would cut their hair short».

Nastya recalls that at that time Ozersk seemed to lag «1-1.5 years behind» Moscow at the time, while Nadezhda appeared to her as if she were a «person from the future». «She seemed like a foreigner or an alien», Nastya reflects. «We simply didn’t have anyone like her at all».

In hindsight, years later, Nastya came to understand that Planet of Hope was also a feminist project. «To me, Nadezhda was the first woman who proclaimed, „I can accomplish anything on my own. And if I can’t, I’ll learn how“. Whether it was mastering English or launching an NGO it left me astonished».

Today Nastya is volunteering at Without Prejudice, the NGO that supports Russian-speaking people who need psychological help because of the war in Ukraine.

Shortly after the opening of Planet of Hope, Nadezhda, along with other activists from Russia, visited the United States as a part of the Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility program. She was struck by the similarity of the problems. «For example, an enterprise in Hanford drains radioactive waste into the Columbia River [like Mayak into the Techa river]», — Kutepova said in an interview in 2007. The author of this publication wrote that it was then that «the image of Nadezhda as an anti-nuclear figure began to emerge».

At the same time, in the early 2000s, Nadezhda began working with Greenpeace. Nastya recalls: «It was as if Elon Musk had landed on his spaceship in the middle of Siberian nowhere right now», Nastya says. «Greenpeace was a word from the TV. Big, serious, scary, and foreign. Well, it also meant the word of the enemy. I was convinced that Greenpeace people may have their ecology agenda, but in Ozersk there is just Ozersk. That we have our own rules. And it was amazing to watch Nadezhda, who did not see this boundary».

In 2003, Kutepova spoke at a joint press conference in Moscow held by Greenpeace and the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which presented a collection of articles entitled «Russia’s Nuclear Power Industry: The Unknown About the Known». «Sociologists and eco-activists have accused the Department of Nuclear Energy of cultivating alcohol and drug addiction at the power plant, — Kommersant commented on the event. The article further added that the power plant engineers themselves denied consuming alcohol, asserting instead that they maintained a highly „civilized“ lifestyle. Additionally, the reporter highlighted „Mrs. Kutepova’s assertion that in 1999, Ozersk ranked first in terms of the rise in drug addiction, with 45 individuals caught heavily intoxicated with alcohol at Mayak the previous year“.

During the same years, Nadezhda met a young lawyer from St. Petersburg, Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov later worked with Planet of Hopes on several occasions as a lawyer on cases of compensation for radiation victims.

«In 2004, a woman and her daughter came to me, both crying», says Kutepova. It appeared that the woman was involved in cleaning up discharges of highly radioactive waste on the Techa River while being unaware of being pregnant. Her daughter fell ill at the age of 40 and it was established that her illness was related to her mother’s radiation exposure. However, there is no such category of disability within the law, so she was not entitled to any state help. The woman complained to Nadezhda crying: «My daughter curses me: „Why did you give birth to such a creep?“» The team of Planet of Hope tried to help the mother and daughter, but unfortunately both of them died one after the other very quickly.

In 2004, Planet of Hope received an American grant to open a human rights reception centre. One of the grant’s conditions was a study of the mentality of the closed cities’ residents. The topic was approved by the Academy of Sciences, and sociologists from St. Petersburg, including Olga Tsepilova, were to come to Ozersk. However, Olga received a call from the Ozersk administration informing her that the study was cancelled. Tsepilova was then called to the FSB. «I was told that I would probably be charged with treason in the form of espionage, that my visits to the FSB would now become long and frequent, that I would visit them more often than I went to work», the sociologist said.

Nadezhda, who was pregnant at the time, recalls that she saw an article about this story the day she arrived at the maternity ward. The Komsomolskaya Pravda title said: «Sociologist Tsepilova tried to enter a closed city for intelligence purposes».

Tsepilova sued the newspaper, but her case was unsuccessful. In May, Kutepova sent an enquiry to the Federal Security Service Directorate of the Chelyabinsk Region, and in August she received a reply that the department had no claims against Planet of Hopes or Olga Tsepilova.

In 2005 Nadezhda enrolled in the Ural Law Academy. Around the same time she went to court for the first time on her own (previously, Planet of Hope had only been represented by lawyers). Her first case was to represent her own mother to get a certificate as a widow of a nuclear disaster liquidator. Nadezhda’s father died in 1985, and the law on support benefits for widows was passed only in 1993. She won that case, and her mother was issued a certificate.

Having studied for one year, Kutepova realised that with three young children she did not have time to get a second degree and took a sabbatical. She decided to «learn on the go». Nadezhda did not return to school from her leave, and received her law degree much later — at the Sorbonne.

«Access to Kirienko»

In 2005, Rosatom, short for the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom, to which Mayak is reported, was headed by Sergei Kirienko. Kirienko is an influential politician in Russia, famous for his «technocratic» approach. He previously served as the Prime Minister of Russia and now is the First Deputy Chief of Staff of the Presidential Administration. The year after he was appointed the head of Rosatom he began resettling residents of Muslyumovo, the nearest village to Ozersk, located on the banks of the contaminated Techa River.

Nadezda tells us that she had already met people from these polluted villages by then, and they perceived her being from the «opposite camp, a valedictorian girl from a closed town», while those people were very poor, not even having the basic comfort at their homes, with outdoors toilets. It took time for Nadezhda to win their trust and start to represent them.

Nadezhda represented Muslyumovo residents who wanted to move into the housing provided by the state (the rest were bought out of their homes by the government for one million roubles each). She says that the initiative group had already managed to find a suitable settlement when the residents were told that there was a village Novomuslyumovo (New Muslyumovo) being built, two kilometres away from the old Muslyumovo. «Why? Because Sergei Kirienko was walking down the street and met an old lady. And he asked her: „Where would you like to move?“ She replied: „Why would I move? I’ll be at the graveyard soon enough. So for me, right here is best“. „All right, then right here is where we’ll build you a new village“».

«To me, Kirienko embodies someone with ominous intentions, veiling them with a facade of kindness. Having collaborated with him, I’ve come to see him as inherently malleable, prone to shifting directions on a whim—a person of questionable reliability», reflects Nadezhda Kutepova on her assessment of Sergey Kirienko, who has served as the first deputy head of the presidential administration since 2016.

When Planet of Hope and environmentalists failed to block the Novomuslyumovo project, Nadezhda began to take on cases of residents who were denied compensation for various reasons. «As soon as we went through all the legal procedures, we were denied everywhere, so we lodged complaints with the European Court — they [Muslyumovo residents] were immediately offered compensation to avoid further noise», Nadezhda recalls.

At the same time, since 2004, her conflict with the FSB over the «case of former convicts» has unfolded. «Under the guise of counterterrorism efforts, the FSB ceased issuing entry permits to residents of closed cities who had served time in prison. This posed significant challenges for the affected individuals», Nadezhda explains. «Mothers of former prisoners resorted to desperate measures to bring their sons home, only to have them apprehended by police upon arrival. Later, they were forcibly removed. The areas surrounding closed cities contain agricultural land owned by residents, which became a refuge for these ex-convicts, leading to a rise in gang-related violence».

Nadezhda handled cases regarding the entry to the city of former prisoners in courts. Thus, gradually, by her own definition, she became «a kind of a sworn enemy» for the law enforcement officers, the leadership of Mayak' and local authorities.

«You have to understand that the FSB has a little file on everyone in Ozersk. Everyone is under scrutiny», Nastya explains.

In 2008, Planet of Hope was accused of tax evasion after receiving a grant. Kutepova is still convinced that the FSB was behind this: «I was pregnant again. The police came to my apartment, to the maternity ward. An FSB officer came to my child’s kindergarten. In general, it was a tough confrontation that suddenly ended in 2009». At that time, the human rights organisation Agora, representing Planet of Hope in court, won the tax case.

In 2010, the position of Human Rights Commissioner was introduced in the Chelyabinsk region, and Kutepova became an advisor to the first ombudsman, politician and lawyer Alexey Sevastyanov. And in 2011, Planet of Hope won the «case of former prisoners» in the ECHR. After this, the courts of closed cities also began to issue decisions in favour of returning convicts.

Another significant victory for Nadezhda was the abolition of the high security clearance status, which until 2013 was a default status not only for employees of Mayak, nuclear power plants, and similar enterprises but also for ordinary residents of closed cities and anyone entering them. «I conducted a constitutional and legal analysis and, using my access to Kirienko, each year from 2005 to 2012, when he visited [Ozersk], I handed him this analysis. After all, what does this status mean for a person: they can be accused of disclosing state secrets at any moment. And then in 2013, I opened a newspaper, and saw that (in the Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 693 on the procedure for special regime in closed administrative-territorial formations with facilities of Rosatom — OVD-Info) they removed the phrase „granting entrance includes obtaining clearance for access to information constituting state secrets“.

According to Kutepova, by 2015, Planet of Hope won about 70 cases in court, but there were many more unsuccessful ones.

«Beautiful, slender, with full lips and four children! You’ll like her», — Rosa (name changed), a former client of Nadezhda, recalls how acquaintances introduced the human rights activist to her. By that time, the woman, a victim of Mayak irradiation, had gone through several lawyers. Only Kutepova was able to help her. Rosa won her compensation case.

Nadezhda indeed has four children. One of them was born with an extra pinky finger on their hand, which was removed at the maternity hospital.

«We left the cat at home»

«Nadezhda lived in Ozersk like on top of a powder keg. The pressure from the authorities was tremendous, yet somehow, she managed. She had support among the local population; they trusted her», says lawyer Ivan Pavlov, who now heads the human rights project First Department.

In 2015, the Ministry of Justice indiscriminately added environmental NGOs to the list of foreign agents. Thus, organisations such as Baikal Environmental Wave, Green World from St. Petersburg, Center for Ecology and Safety Training from Samara, Dront Environmental Center from Nizhny Novgorod, and others became labelled as foreign agents — a status akin to «enemy of the people» designed to harass and pressure targeted organizations and individuals.

Nadezhda Kutepova thought that as the assistant to the ombudsman, she would not be affected, but on 15 April, she received a call from the TV Rain, asking if she knew that Planet of Hope had been labelled as a foreign agent. Kutepova was unaware. Later, from the court decision, she found out that the Ministry of Justice included her NGO on the list because of three publications. One of them was an article about the case of Regina Khasanova, the granddaughter of a liquidator of the accident at Mayak. She died at the age of six due to the radiation exposure on her grandmother. Officials considered such publications as «evidence of political activity» by Planet of Hope.

Nadezhda insists that Planet of Hope was never acting in the interests of foreign states. Its activity was solely in the interests of the citizens of the Russian Federation and, in particular, those of the Chelyabinsk Region who had suffered from the actions of the Мayak enterprise and its secret and known accidents. «There are no foreign countries that would be interested in protecting these people», she tells us.

At the end of Мay, state-funded television channel Russia-1 ran a segment (now unavailable) in which presenter Olga Skabeyeva accused Planet of Hopes of «industrial espionage with the use of American money». The second segment, where Skabeyeva disclosed Kutepova’s address, came out on 2 July.

The interior of the flat that Skabeyeva tried to get into, was later shown in the documentary City 40 made by an Iranian-American documentalist Samira Goetschel. It showed a ragged carpet covering cheap vinyl floors, half-torn wallpaper, a basket of toys, a punching bag; a shabby corner and tiles with uneven cement streaks in the kitchen.

Nadezhda «packed her whole life into bags in three days». «I left my phone at home. We left our cat at home». On 7 July, Nadezhda and her three children (the fourth, an adult, stayed in Russia) landed in Paris. She had divorced her husband back in 2009.

In April 2016, Nadezhda was granted political asylum in France. At the beginning of 2017, the family reunited with their cat.

Apart from Kutepova, there were five more people working for Planet of Hope by 2015. Soon, three of them left Ozersk as well and none of the former employees continue their human rights activities. In Мay, the organisation was fined 300,000 roubles (US$ 3,200) because Nadezhda had not asked to include her in the list of foreign agents. «Naturally, we did not pay [the fine], it was the matter of principle», the activist says. According to her, Planet of Hopes was fined twice more, and «the debt sum was nearly one million». Despite this, Kutepova tried to «work remotely».

«Such was their desire to get rid of us»

On 2 October 2017, Italian scientists detected Ruthenium-106 in the air in Мilan. Ruthenium-106 is a radioactive isotope last recorded in the atmosphere after the Chernobyl disaster. Within several days more than twenty European countries confirmed the presence of Ruthenium-106 in the atmosphere. The German Federal Office for Radiation Protection (Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz) determined that its likely source was in the Southern Urals. Rosatom stated that there had been no accidents at its facilities.

«This fuss, strangely enough, coincides with the 60-year anniversary of the Мayak accident [1957]. It might well be a political game: cause panic first, then demand additional information. This looks like industrial espionage already», declared the Мinister of Public Security of the Chelyabinsk Region Evgeniy Savchenko.

In mid-October, Nadezhda Kutepova was the first to publicly suggest in the commentary for the Kommersant newspaper that the contamination occurred because of an accident at Мayak, where new equipment was being tested at the end of September. In November, The Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring (Rosgidromet) admitted that since 25 September, all the posts in the Southern Urals had been registering excessive background radiation. Notably, in a settlement near Ozersk the contamination had increased by nearly a thousand times compared to August.

According to environmentalists, the leak was mainly dangerous for those near the source. European countries regarded the threat to the public as insignificant. The 2019 study with 69 scientists from various countries participating in it confirmed Nadezhda Kutepova’s version about the source of the contamination. Russian authorities have not recognised the accident at Мayak so far.

Legally, Planet of Hope existed for three more years after Nadezhda was forced to emigrate. In 2018, she opened the Russian legal entities register and found out that the organisation had been liquidated «due to the absence of activity»: «They closed us down with for debts. Such was their desire to get rid of us, I guess».

Kutepova considers discovering the source of the ruthenium cloud the most important story at the final remote stage of Planet of Hope’s work.

«I would like to close down the factories»

Before 2022, Ozersk residents used to find Nadezhda through her former clients and ask her for legal help: «I only took the case if I saw some prospects at the pre-trial stage. I won over 70 cases, but I handled each of them myself [in the courts]. I will say without false modesty that my personal presence had an effect».

Kutepova’s book «Secrets of Closed Cities» came out in 2021: «This was a quintessence of my activism in the field of human rights in Rosatom’s closed cities». Its last part contains the practical guide with legal examinations, a handbook and document samples. When receiving a request for help, Nadezhda would give them the link to the book.

However, after 24 February 2022, the communication with Ozersk residents has broken down, says Kutepova: «They just stopped the contacts, didn’t reply to letters. I only see that they like something on [my] Instagram sometimes».

Nadezhda opposed the full-scale invasion of Ukraine from the start. For the past two years, Nadezhda has been regularly commenting on the war for French media. According to her estimates, during this time she had no fewer than 150 appearances on local television channels. She has long hair pulled back into a bun, bright red lipstick, and a silk scarf around her neck. In fluent French the «political refugee from Russia» (that’s how Kutepova is usually introduced) says: «Vladimir Poutin ne s’arrêtera pas si l’Ukraine est cédée» («Vladimir Putin won’t stop if Ukraine is surrendered»).

Recently, Nadezhda Kutepova completed an autofiction titled «Daughter of Russia is Hope». She is now looking for a publisher. «I believe my life story shows how things have changed over time, including [the situation with] „foreign agents“», explains Nadezhda.

Regarding human rights initiatives for Ozersk residents, here’s what she says: «As soon as the war ends with Ukraine’s victory, I’m planning to challenge the International Atomic Energy Agency on the Mayak issue. I am determined to get the inhabitants of Novomuslyomovo and other villagers living along the Techa River relocated. Moreover, I want to ensure compensation for all victims of the 1957 accident. And I would also like to see the plants involved in processing radioactive waste and producing plutonium shut down. Is it a fantasy? Let’s see».

«[At the moment], I am better known within the French community, but not as much within the Russian-speaking one. They simply forgot about me», adds Nadezhda. But she is occasionally mentioned in VKontakte social network groups related to Ozersk: «Ah, Nadia, Nadenka. She could have worked quietly as a sweet nurse, but no, she had to dabble in politics»; «Nadezhda was paid off through and through; only the dollar motivated her»; «We should „thank“ her for the fact that repeat offenders and junkies began to return to the city after many years behind bars»; «Funny woman, back in the day she used to say that we don’t need nuclear power plants or Mayak, and can watch TV while lightning a candle!»

But you know, for me, the nicest thing was that after I left, the Kremlin’s Channel One tried to make a [propagandistic] film, but people refused to testify against me. They did not speak up in defence because fear is really present. But no one agreed to accuse me», says Nadezhda.

The discussions about closing Mayak, however, are not well-received by the residents of Ozersk. The average salary at the town’s leading enterprise is 80,000 rubles (US$ 870), higher than elsewhere nearby. The shutdown of Mayak is economically disadvantageous for the residents. «If Mayak survives, the city survives», one of the subjects from last year’s report from Ozersk told a correspondent from the publication 74.ru.

Kutepova knows about the situation in Ozersk after her departure from the accounts of the residents and believes that it has changed for the worse. There is a shortage of doctors, and the roads are in poor condition. Her conclusions are partially confirmed by the author of the publication on 74.ru. «The residents, as it turned out, are not thrilled with the condition of the hospitals, the doctors, or the medical equipment». Nonetheless, the journalist calls local roads a «bar of chocolate». In his summer snapshots, you’ll find renovated facades of post-war two-story Stalin-era buildings, a well-maintained embankment along Lake Irtyash, and an abundance of greenery.

In the closed city of Ozersk, violent crime is almost nonexistent. Out of nearly a thousand registered crimes from the past year, the majority were computer and telephone fraud with the main victims being veterans and employees of Mayak. The police suggest «engaging professional psychologists» to conduct preventive work with them.

Despite the social prosperity of Ozersk, mortality in the town significantly exceeds the birth rate. In 2023, the local registry office registered 454 newborns and 1068 deaths. In January of this year, 28 people were born in the closed city, while 126 died; in February — 25 and 79; in March — 25 and 99 people respectively.

And every day, just like 75 years ago, the Mayak nuclear plant fulfils state defence orders by producing plutonium-239, a component of nuclear weapons.

The Planet of Hope participated in the lawsuit «Ecodefence and Others vs. Russia». Besides Nadezhda Kutepova and the Ecodefence organisation — a Kaliningrad-based group established in 1989 and added to the foreign agents list a decade ago for its opposition to the construction of the Baltic Nuclear Power Plant, 71 other organisations were involved in the lawsuit. These included the human rights association Agora, the LGBT organization Coming Out, the Committee Against Torture, the Samara-based publishing house Gagarin Park, and others. In June 2022, the ECHR ruled that the legislation on «foreign agents» did not comply with the requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights. All participants in the lawsuit were awarded €10,000 each in compensation for moral damages.

In February 2024, lawyers from the Human Rights Centre Memorial, together with OVD-Info, the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis, the Civil Control human rights organisation, and the Public Verdict Foundation, submitted a petition to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe regarding this case. Human rights activists have reported that over the past year and a half, the situation in Russia has deteriorated further, with «anyone or anything» being labelled as a foreign agent. In detailing the impact of the foreign agents law, the authors of the petition noted that as of 6 February 2024, out of the 763 organisations listed by the Ministry of Justice, 147 had either permanently or formally ceased operations—either voluntarily or by court order.

On 13 March the Committee demanded that the Russian authorities abandon the legislation on «foreign agents».

Galya Sova